Useful Cinema

Edited by Charles R. Acland and Haidee Wasson

Duke University Press, 2011

Reviewed by Andrew James Myers

“Breadth” is a descriptor often mentioned for edited volumes, and so labeling Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson’s Useful Cinema as “broad” would sound trite. A book such as this, which aims to include in its scope the whole range of motion picture history outside of the classic category of the theatrical fictional film, can only be described as vast, immense, and staggering. The editors’ few geographical and chronological limiters do little to diminish the sheer scale of the topic. This hyper-breadth is, indeed, one of the central insights of the volume: in clearly sketching out the sweeping dimensions and intellectual fertility of “useful cinema’s” academic frontier, the book offers an enticing call and new analytical tools for further scholarship on the “other film history.” From experimental film to the spectacle of the planetarium, from African American WWII newsreels to Western Union’s training films, the collected articles cover disparate permutations of historical context, technology, institutional patron, format, and exhibition venue. Uniting this extensive assortment of texts and contexts is a common interest in analyzing how moving image texts are embedded in the histories of social formations and institutions. This volume’s authors endeavor to piece together not only how socio-political interests and discourses determine the production history of non-theatrical films, but also how those films, in turn, shape and mold social reality to further institutional objectives.

Those who are familiar with recent anthologies in the emerging area of non-theatrical film studies — such as Hediger and Vonderau’s Films that Work: Industrial Film and the Productivity of Media; Orgeron, Orgeron, and Streible’s Learning with the Lights Off: Educational Film in the United States; and the National Film Preservation Foundation’s Treasures from American Film Archives series2 — will already be acquainted with the range of “non-theatrical,” “educational,” “sponsored,” “functional, “non-fictional,” “industrial,” “orphan,” “ephemeral,” “minor” and “marginal” forms that Acland and Wasson corral under the term “useful cinema.”3 The question is inevitable: do we really need another term?

As it turns out, “useful cinema” is indeed a useful term — not so much as a definition for a category of films but as an analytic lens through which various overlapping categories of non-theatrical, industrial, educational, and orphan films can be viewed in new light. This approach draws attention to the utility of film, to what social functions and purposes these films fulfill. Consideration is given not only to uses but also to users. How did the demands of social and institutional frameworks — whether national, civic, corporate, educational, or otherwise — produce and exploit these films? In Acland and Wasson’s formulation, “useful cinema” comprises “a body of films and technologies that perform tasks and serve as instruments in an ongoing struggle for aesthetic, social, and political capital.”4 Defined in this way, the concept “does not so much name a mode of production, a genre, or an exhibition venue as it identifies a disposition, an outlook, and an approach toward a medium on the part of institutions and institutional agents.” 5

While the book’s focus is primarily social history rather than theory, Acland and Wasson offer some theoretical foundation for the project. The editors notably draw on the notion of “useful culture” put forth by Cultural Studies scholar Tony Bennett, which suggests that culture is most appropriately analyzed in terms of “its practical deployment within … governmental processes.” Bennett has convincingly argued that “what a text is, and what is at stake in its analysis, depends on the specific uses for which it has been instrumentalized in particular institutional and discursive contexts.…”6 Expanding upon Bennett’s theoretical groundwork, Wasson and Acland posit cinema as a subset of useful culture and aim to reorient critical attention toward the “institutional dimensions of cultural life that have tended to fall by the wayside in our received historical narratives.” 7 While issues of past archival neglect for “useful cinema” are not treated substantially in this book, many of the works in this collection are strongly indebted to the work of scholars, archivists, and collectors such as Rick Prelinger and Dan Streible who have worked to rescue orphaned nontheatrical films from cultural obscurity and literal destruction. Thus the works of this collection can also be seen as an extension and compliment of preservation initiatives for nontheatrical, “orphan” films.8

In accordance with Useful Cinema’s primary emphasis on how organizations use media, many of the collected articles rightly emphasize the institutions themselves much more than individual film texts, showing the various ways in which an assortment of organizations conceptualized the film medium in relation to their established interests. Some of these essays forgo textual analysis altogether; for instance, Eric Smoodin’s essay “What A Power for Education!” analyzes the 1930s “film education movement” by focusing on pedagogical discourse, opening insights into the relationship between film culture, schools and libraries, and the film industry. In Smoodin’s thorough discussion of these institutional dynamics of the pedagogical use of film, he scarcely even mentions titles of films, and he never analyzes individual movies themselves. Conversely, several other authors are able to deploy visual analysis in a highly integrated manner, such as in Kirsten Ostherr’s fascinating explication of the martial metaphors incorporated into wartime medical education films.

The history of “useful film” has a clear contemporary relevance when considered in light of the ubiquity of moving images in the current age of new media. Useful Cinema argues that the modern configuration of mediated institutions, bodies, and spaces stems not from a new media revolution but rather from the long-term gradual integration of cinema into everyday arenas and a progressive expansion of the visual literacy of both audiences and institutions. As contemporary media scholars work to refute currently prevalent fallacies of technological determinism (particularly surrounding social networking and mobile devices9), they would do well to draw on these essays’ demonstration that technological revolutions must be situated in a historical context of broader cultural forces.

This focus on fully contextualizing technological development is clearly articulated in a number of essays’ discussion of the advancement of the 16mm film standard. 16mm expanded media’s presence to various non-theatrical cultural spaces and marked a key point of industrial convergence between various discrete forms of non-theatrical film, such as educational, avant-garde, museum, and industrial film. In the history of the 16mm format, technological innovations are only one half of an equation that also includes, as Stephen Groening articulates, “the discursive positioning of film as a viable and valuable educational tool.”10 16mm (like any potential new format) required investment, effort, and optimism from multiple sectors: technology manufacturers, film producers, and consumer exhibitors (such as schools and companies). As Charles Acland notes in his discussion of Hollywood’s 1930s initiatives to jumpstart an educational film market, “A perennial problem to the development of motion pictures in education was that schools were not investing substantially in projectors because of the lack of films, and few films were being released for instructional usage by the Hollywood majors due to the absence of projectors.”11 16mm as a format thus faced an uphill battle in claiming its eventual status as the primary medium and infrastructure for non-theatrical film. Its ultimate rise to prominence in the period between 1935 and 1945 came only through intersecting yet uncoordinated efforts of a number of separate institutions in a particular historical and cultural context.

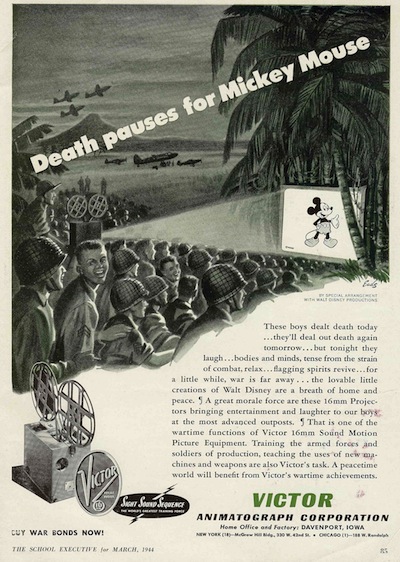

Greg Waller’s essay “Projecting the Promise of 16mm, 1935-45,” reviews the optimistic pronouncements about the future possibilities of 16mm technology used in the advertising and publicity material of projector manufacturers. Positioning the technology as one of portability and ubiquity, these ads suggested that any social space — from churches, homes, and schools, to factories, hotels, and parks — could cultivate a movie audience. Also integral to the public discourse about 16mm were the US government’s various deployments of 16mm film during World War II, both on the battlefront and at home in support of War Loan drives.12 The advertising discourse of this period thus worked to “sell 16mm as an essential wartime technology that should prove to be no less essential in postwar America.”13 Thus 16mm’s successful rise as a standard infrastructural format for non-theatrical film in the US from 1935-1945 was, to a large extent, bound up in the ways manufacturers and government entities exploited the medium to address that era’s particular socio-political circumstances.

Victor, Death pauses for Mickey Mouse, Home Movies(1944)

Ronald Walter Greene addresses the adoption of 16mm from another perspective, that of the YMCA’s Motion Picture Bureau, which sought to pursue its pastoral goals by distributing low-cost films and projection equipment to churches, clubs, industries, schools, and YMCAs.14 Greene sees the YMCA’s attempts to hasten the transition from 32mm to 16mm as not simply an adoption of a new technology but also as a struggle to evangelize a “culture of 16mm” to its affiliated exhibitors and as a mission to explore and exploit the possibilities of this mobile, flexible medium.

Aside from issues of technology, a number of other topics are explored fruitfully through the optic of utility. Mention of just two more articles will provide a further sense of the variety of unique scholarship the book offers. Alison Griffiths’ essay on Planetarium shows, entitled “A Moving Picture of the Heavens,” winds her way through a complex trajectory of the planetarium’s history bound by conflicting interests in, on one hand, gimmick-free scientific accuracy and, on the other, an appeal to showmanship to convey the wonder of the universe. Griffiths sets the partial incorporation of the film medium into the planetarium show against a backdrop of technological change (with both film/video and the Zeiss star projector), the phenomenology of spectacle, historical manifestations of nationalist supremacy (such as the space race and the cold war), discourses of spirituality, and other cultural dynamics. Griffiths’ elegiac account is colored by nostalgia for the “immersive simplicity” and unmatched clarity of the Zeiss star projector—a technology that, in many planetariums, has been phased out in favor of film– and video–dominated programs. Quoting her teenage son, she describes Hayden Planetarium’s show as “Like a movie but somehow different.”15 This opens up Griffiths’ dual lines of inquiry: first, how planetariums have adopted the technologies, formal elements, and special effects of cinema, and second, how the same planetariums have simultaneously sought to assert the difference of their programs as a unique cultural form distinct from the movies.

Charles Acland’s entry, “Hollywood’s Educators: Mark May and Teaching Film Custodians” considers the aftermath of the well-known Payne Fund Studies (a landmark early media effects study) by launching into what, at first, appears to be an enormous tangent. Acland tracks several decades of the career of Mark May, one of dozens of Payne Fund researchers, providing a curious and illuminating window into the surprising flurry of activities through which the MPAA (and its immediate predecessor, the MPPDA) established and strengthened Hollywood’s institutional ties to the educational film market. A 1937 Advisory Committee, formed by MPPDA Chairman Will Hays on May’s recommendation, surveyed existing films for their potential utility in the classroom, winnowing down thousands of shorts to a catalogue of a few hundred. When the Advisory Committee realized it had to devise a method for distributing these films, the committee was spun off into a non-profit distribution corporation named Teaching Film Custodians, with Mays at the head for a four-decade tenure. Mays continued to participate in other MPAA research projects, such as one that involved school children in scientific experiments to determine the most effective kinds of educational films. Acland sees personalities like May, who spanned a range of roles in the educational field, as exemplifying a postwar trend on the part of the motion picture industry toward coordinating and integrating educational film production, testing, market research, and distribution. While Acland frames his overall analysis in terms of Hollywood’s political economy, he verges beyond a simple characterization in which Hollywood’s forays into educational film are simply another form of the industry’s desire to extend its hegemony into new markets. May, in this portrait, comes off not as a researcher co-opted by Hollywood to extend its power and fortune, but rather as a savvy and socially-invested researcher who was able to forge a steady alliance with the industry to pursue mutually beneficial interests in developing educational film. As contemporary studies of media industries continue to gain traction, modern scholars attempting to forge research partnerships with industrial institutions (such as those affiliated with the nascent industry-funded Media Industries Project at UC Santa Barbara) can look to past industry-embedded scholars like May as an insightful model.

One matter largely absent from this volume but deserving further consideration is the role of both the archive and the university in defining media studies’ conception of useful cinema. As Caroline Frick (in chorus with others) has argued in Saving Cinema: The Politics of Preservation, the decisions, values, and practices of media preservation archives — themselves situated in a complex web of politics and institutional interests — have largely defined how academics and the public have understood American cultural heritage.17 To the extent that archives have, in recent decades, increased their efforts to preserve and provide access to useful cinema, what new uses might such orphan works provide media archives? And how might scholars historically situate the recent academic surge of interest in these films — what new utility do they provide to individual scholars and to the field of media studies? Hopefully these will be questions to which more scholars will return as critical attention continues to turn toward non-theatrical film history.

Useful Cinema Co-Editor Haidee Wasson also (with Lee Grievson) co-edited an excellent collection of essays on the history of academic film and media studies, Inventing Film Studies.18 A fitting follow-up or response to Useful Cinema might emulate Inventing Film Studies’ reflexive and situational account of academia in order to clarify the institutional forces governing non-theatrical media studies and archiving. Such an analysis (though it might sound to some like frivolous academic navel-gazing) would matter deeply to scholars whose research interest in non-theatrical film might be limited by fear that their work in this area would be perceived as only marginally relevant to their university teaching assignments. Multiple scholars of non-theatrical film have expressed to me a view that undergraduate course offerings entirely devoted to educational and industrial film would be a hard pitch to students. These professors instead tend to incorporate one-or-two-week units of non-theatrical film into the syllabi of other more established courses like documentary history, American film history, or media industries. Further discussion on non-theatrical film should seek to identify which cultural and institutional realities keep non-theatrical film a marginal topic in university teaching, and how the priorities and interests of students and film/media departments can be expanded to embrace its study.

One aspect the book leaves to be desired (somewhat ironically, given all its attention to film’s usefulness in the classroom) is that many of the films discussed are not widely available for viewing. On one hand, the authors’ focus on culling difficult-to-access primary materials through deep archival research has uncovered insights unavailable to other scholars. On the other hand, especially in the unfolding age of the digital humanities, an omission of visual material seems to undercut the potential of the project. In contrast, the aforementioned 2011 collection of essays Learning with the Lights Off (which features many of the same contributors) made accessibility a high priority by including notes on access in the filmography at the end of each chapter and providing numerous links to referenced audiovisual material via a companion website. Useful Cinema’s filmography ought to similarly help readers locate archive sources for films under discussion. The occasional footnote does suggest availability at Archive.org or on a DVD release, but by and large interested readers are left to do their own research as to where referenced films might be available.

Know For Sure (1941), produced by Darryl F. Zanuck, from the Internet Archive.19

For instance, Kirsten Ostherr’s fascinating case study on health films during the cold war includes one of the films, The Body Fights Bacteria (1948), in its title, yet nowhere does the book offer any help in locating its archival source20. Occasionally it is unclear whether an author has actually seen a film or whether (as suggested through a citation) they have simply read a secondary account. Readers who are willing to plumb footnotes, academic databases, and search engines may access the occasional gem online — such as the above-embedded 1941 Daryl F. Zanuck-produced film on syphilis diagnosis and treatment — but the general lack of access to view the films that are discussed throughout means that despite the high quality of the essays, this book would be difficult to rely upon as the primary text for a course on non-theatrical film.

Its minor limitations, however, do not diminish Useful Cinema’s quality as a wholly solid collection of new research in a blossoming area of study. Each of Useful Cinema’s articles offers unique, substantial, and interesting work that will engage and benefit any scholar even peripherally interested in the socio-cultural and socio-political dimensions of educational or industrial film. As Useful Cinema shows, non-theatrical film is a wide-open academic frontier with relevance far beyond the topic of media— a film history that fully accounts for the dimension of usefulness is indeed, first and foremost, a history of institutions, their discourses, and their interactions with the larger social realm. This collection doesn’t necessarily provide revolutionary insights into the field, nor are the questions the volume raises entirely new. Useful Cinema’s more modest goal is to take a solid step into the still largely unwritten history of America’s “other” film culture, and in that goal it succeeds emphatically. As broad as its subject matter may be, the volume is unified by a rigorous standard of archival scholarship, a remarkable tendency to build interest and delight in unexpected topics, and a consistency of accessible writing that clearly illuminates how film and media are used to write and rewrite social histories.

NOTES

- Charles R. Acland and Haidee Wasson, eds., Useful Cinema (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

- Devin Orgeron, Marsha Orgeron, and Dan Streible, Learning with the Lights Off: Educational Film in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012); Vinzenz Hediger and Patrick Vonderau, Films That Work: Industrial Film and the Productivity of Media (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press, 2009); Scott Simmon et al., Treasures from American Film Archives: 50 Preserved Films, Encore Edition (United States: Image Entertainment, 2005); Karen L. Ishizuka and Patricia R. Zimmerman, eds., Mining the Home Movie: Excavations in Histories and Memories (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

- The various terms listed here are all terms used by scholars who study what may be most broadly categorized as “non-theatrical” film and media. “Non-theatrical” is a common term referring to forms and genres outside the mainstream of fictional theatrical cinema. Of the other listed terms, some refer to broader categories and wider scopes than others. Narrower terms like “educational film” (referring to film created for or exhibited in a pedagogic setting, such as a school or library) and “industrial film” (defined as film created and used internally by business or industry) categorize non-theatrical films based on their specific contexts, while broader terms such as “orphan film” or “marginal film” refer to the general neglect many of these moving image texts have received from film librarians, historians and archives on account of their lack of cultural status. Many of these various terms share overlapping qualities with others, but one should not assume them all to be synonymous. The term “useful cinema,” as defined by Wasson and Acland, intersects with many of these terms but also seeks a more expansive theoretical scope by cutting across boundaries of fiction, non-fiction, and experimental film. See Acland and Wasson, Useful Cinema, 4.

- Acland and Wasson, Useful Cinema, 3.

- Ibid., 4.

- Tony Bennett, “Useful Culture,” Cultural Studies 6.3 (1992): 395–408.

- Acland and Wasson, Useful Cinema, 13.

- Dan Streible, “The Role of Orphan Films in the 21st Century Archive, Cinema Journal 46 (Spring, 2007): 124-128.

- I especially have in mind here simplistic but widely proliferated media characterizations of the 2011 “Arab Spring” as a “Facebook Revolution” or “Twitter Revolution” — a political upheaval catalyzed primarily by social media. For a representative example of this technological determinism, see the two-part television documentary, How Facebook Changed the World: The Arab Spring, produced by Ricardo Pollack (UK: BBC Two, 5 Sept 2011). For more skeptical perspectives on digital media’s role in social change, see: Francesca Comunello and Giuseppe Anzera, “Will the Revolution be Tweeted? A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Social Media And The Arab Spring,” Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 23:4 (2004); Malcolm Gladwell, “Small Change: Why the Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted,” The New Yorker, October 4, 2010, http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/10/04/101004fa_fact_gladwell

- Stephen Groening, “’We Can See Ourselves as Others See Us’: Women Workers and Western Union's Training Films in the 1920s,” in Useful Cinema, 36-37.

- Charles R. Acland, “Hollywood's Educators: Mark May and Teaching Film Custodians,” in Useful Cinema, 67.

- The WWII War Loan Drives were fundraising campaigns by the US Government in which citizens were encouraged to purchase war bonds. Washington created and disseminated a number of patriotic films with the aim of popularizing the bonds among the public.

- Gregory Waller, “Projecting the Promise of 16mm, 1935-45,” in Useful Cinema, 138.

- Ronald Walter Greene, “Pastoral Exhibition: The YMCA Motion Picture Bureau and the Transition to 16mm, 1928–39,” in Useful Cinema, 213.

- Alison Griffiths, “‘A Moving Picture of the Heavens’: The Planetarium Space Show As Useful Cinema,” in Useful Cinema, 252.

- Ibid., 251.

- Caroline Frick, Saving Cinema: The Politics of Preservation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- Lee Grieveson and Haidee Wasson, eds., Inventing Film Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008).

- Know For Sure, directed by Lewis Milestone, produced by Darryl F. Zanuck (Research Council of Academy Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, 1941), http://archive.org/details/know_for_sure.

- “The Body Fights Bacteria” is available at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda Maryland — I learned of this archive’s existence in the filmography for Ostherr’s article in Learning with the Lights Off.

Review of Useful Cinema by Andrew Myers is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.