Murder and Montage: Oliver Stone’s Hyperreal Period

by Randy Laist, Ph. D.

Murder and Montage: Oliver Stone’s Hyperreal Period

Oliver Stone achieved celebrity status as an auteur of vitriolic protest films that employed naturalistic realism to challenge the escapist tone of Reagan-era cinema. His directorial debut, Platoon (1986), is a full-frontal assault on the sanitization, or science-fictionalization, of combat that characterizes the cinematic aesthetic of the 1980s. Wall Street (1987) and Born on the Fourth of July (1989) are also both protest films whose dissenting messages are directed not only toward the social and political culture that their narratives dissect, but also against a cinematic culture which has devoted itself to distracting audiences rather than provoking or enlightening them. In his major films from the 1990s, however, JFK (1991) and Natural Born Killers (1994), Stone’s style of protest cinema becomes substantially more radical. Abandoning the naïve mimesis of naturalistic realism, JFK and Natural Born Killers incite their audiences not by journalistically exposing social problems, but by deconstructing the fabric of social reality itself. These films reconceive cinema not as a tool of mimesis, but as a window into an alternate mode of reality that blends reality and representation into a hybrid ontological register. The nature of this uncanny mode of reality is memorably captured in Jean Baudrillard’s seminal observation that “Today abstraction is no longer that of the map, the double, the mirror, or the concept. Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being, or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal.”1

JFK and Natural Born Killers hold a privileged place in the cinematic discourse of the hyperreal. In both of these films, Stone embraces a directorial style characterized by rapid montage, the editing together of different types of film stock, and self-consciously cinematic visual effects, all of which represent significant stylistic departures from the narrative realism of his previous works. Critics who accuse Stone of engaging in pointless MTV-style theatrics overlook the sense in which rapid-fire image shuffling is not merely a stylistic feature in these movies, but rather a central thematic concern.2 As a pair, the films articulate the thesis that history, society, and consciousness itself have taken on the form of a hyperreal precession of mediated images. Under this Baudrillardian premise, the conventional protest film becomes outmoded. Rather than providing a window onto a secret reality, JFK and Natural Born Killers portray and, indeed, enact a fusion of representation and reality.

One of the characters in JFK opines that ever since Kennedy’s death, American existence has been characterized by “an air of make-believe.” In response to critics of the movie who derided the conspiracy theory JFK appears to advance, Stone has stated that his film is not intended as a documentary-style explication of a historical truth, but rather is intended to erect a “counter-myth” against what he considers the official myth propagated by the Warren Report.3 As spectators, we inhabit a world where all we have access to are the myths, representations, and simulacra, the real having off and vanished in a puff of gunsmoke along with our “slain father-leader.” More so than any particular theory about who shot JFK, the thesis of Stone’s film is that reality itself has been assassinated, under circumstances that we can only reconstruct out of a montage of images, ambivalently real and/or unreal – the fragments of a hyperreal mediascape. Stone conceives Natural Born Killers’ Mickey and Mallory as personifications of this new hyperreal environment. Leaving behind any aspiration to social realism, Stone paints a world of antisocial hyperrealism intended to represent not the “real” world, but a picture of the cultural condition we inhabit in the wake of an assassination of reality.

Baudrillard himself described the Kennedy assassination as an important moment in the hyperrealization of the modern world. “The Kennedys died because they incarnated something: the political, political substance, whereas the new presidents are nothing but caricatures and fake film.”4 More than just a political assassination, November 22, 1963 was the date of an ontological assassination. Stone conveys this in the film partly through the idealized image of Kennedy that is minted in the first few minutes and burnished throughout; the Camelot picture of a brilliant, youthful, wise, and virtuous leader. Kennedy himself, however, is absent from the film, save for appearing in a few bits of footage in which he delivers famous lines from speeches and in the representation of his assassination. Kennedy never appears as a look-alike actor in the recreation of a secret meeting, like so many other historical figures do throughout the movie. Kennedy exists in the film only as a scattered jumble of clues, many of which are filmic images, including his appearances in footage from the Kennedy’s home movies, newsreel clips, and the Zapruder film. As a result, the movie that so effectively undermines the public personae of figures such as LBJ and Earl Warren by showing them behind closed doors as conniving and self-serving elevates the mythic status of John Kennedy by representing him only as an icon. There would be something sacrilegious about including a scene in JFK in which Kennedy himself were represented as taking part in political negotiations. He exists in this movie as a superhuman entity associated with the mythical realm of “the real” from which contemporary human beings recognize that they have been exiled.

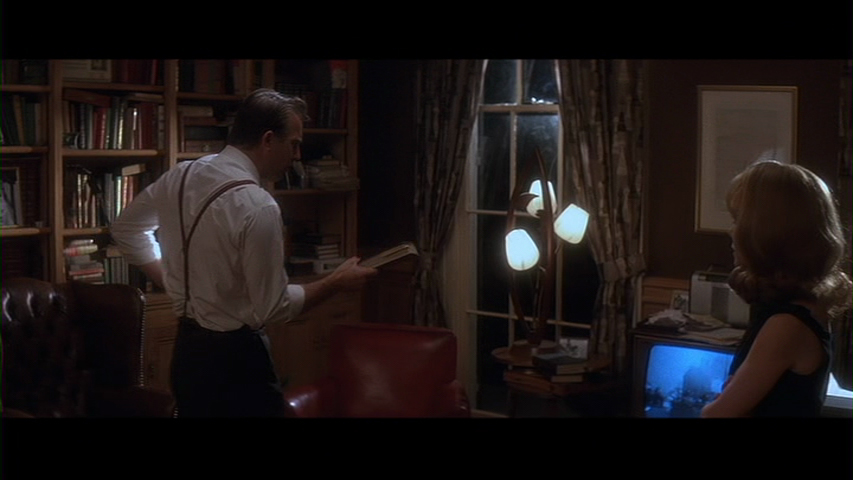

Stone dedicates his movie “to the young, in whose spirit the search for truth marches on.” The last ten minutes of the film consist of a passionate appeal by Jim Garrison concerning the importance of “the truth.” Stone’s film, however, is surprisingly cavalier about “the truth” of both Kennedy’s and Garrison’s historical identities. Outside the film, Stone concedes that Kennedy’s Camelot was “as much an optical illusion as Eisenhower’s golf game” and that the “Jim Garrison” of JFK is an “idealistic archetype” of the historical figure, tracing his lineage back to Frank Capra and Jimmy Stewart.5 Although literal-minded critics have attacked the apparent contradiction between the film’s commitment to “truth” and Stone’s free use of dramatic license, a more nuanced response to this feature of JFK would be to recognize that Stone’s film intentionally dramatizes the conspicuous elimination of truth from the public discourse. Rather than historical figures, we have heroes and villains. Rather than facts, we have clues. Rather than a narrative, we have a proliferation of hypothetical scenarios. Stone describes his attempt to capture this hyperreal style in JFK. “I make people aware that they are watching a movie. I make them aware that reality itself is in question. [JFK] represents a new era in terms of my filmmaking. The movie is not only about a conspiracy to kill President Kennedy but also about the way we look at our recent history.”6 Stone suggests that the most salient feature of our perception of recent history is precisely this destabilization of the nature of reality itself. The entirety of JFK is characterized by a luminescent sheen that indicates how the world being shown is not the historical period that it describes, but a cinematic parallel reality. The lighting throughout JFK transforms even the realistic scenes into surreal mindscapes. When Garrison and his staff meet at a restaurant, for example, bizarre luminescence emanating from the table transforms the mundane setting into a theatrical spectacle of glare and shadow. The cameo celebrity appearances that glut JFK (Jack Lemmon, John Candy, Edward Asner, Walter Matthau, Donald Southerland, etc.) promote a similar hyperrealizing effect. Stone’s commingling of American history and A-list celebritydom holds the audience’s attention in two locations at once. At the same time that we are being promised a scrap of reality, we are reminded that we exist in a world of actors, representations of people simulating the real thing. Frequently in JFK, the actors overact their historical parts so operatically that the performance itself draws attention to its provenance within the genre of drama.

Another prominent feature of JFK is the significant amount of time the characters spend watching television. Stone mentions that he wanted to depict the way in which the media “leapt into major prominence in our public consciousness as an entity that fateful day”7 of the assassination. As the audience of the film, we watch television along with them, but when we watch television in JFK, we don’t simply observe; we become transported through the screen into the action being depicted on the other side. When the Garrison family is watching Lee Harvey Oswald speak at a press conference, the scene cuts away to the conference itself. We see more than what the Garrison family views on television, thus establishing our particular spectatorial position as more able-bodied and powerful than theirs. Stone’s frantic camera bounces us around the press conference room, as if we were being jostled along with the crowd of reporters. At one point, the camera zooms in on one individual to suggest that a voice in the crowd belongs to Jack Ruby. When Garrison sees Oswald shot on television, Stone again cuts away to jumbled images of motion, confused angles of the Dallas police station basement, and a close up of Oswald’s dying face. Stone’s filmmaking in these and similar sequences suggests not only the phenomenologically “real” character of live television – the sense in which watching something significant happen on television is a visceral experience capable of duplicating the shock effect of reality itself – but also, paradoxically, that what we see on television is not the complete reality, but only a single fragment of an infinite array of possible perspectives on the televised event. Again, the reality of representations and the constructed character of reality are held in a complex interdependency. The unresolvable nature of this dilemma of the relationship between fiction and reality is part of the larger unsolved mystery at the center of JFK. The same technique characterizes Stone’s use of the Zapruder footage at the beginning and end of the film. Stone compulsively intercuts actual Zapruder footage with reconstructed footage of the same event from other angles, filmed on other film stocks. At the same time that Garrison’s epic closing argument focuses on the Zapruder film as the most vital piece of evidence in his search for the truth, the Zapruder film is only capable of producing mysteries, rather than resolving them. Garrison believes that the footage is the key piece of evidence to prove that there must have been a second shooter. Frame-by-frame analysis demonstrates that the Warren Commission report was “a fiction” and that a mystery certainly exists. The Zapruder film, however, is unable to offer Garrison anything more specific about how the mystery is to be solved. Stone depicts the medium of film itself as a barrier that lies between Garrison and the truth as much as it promises to become a window.

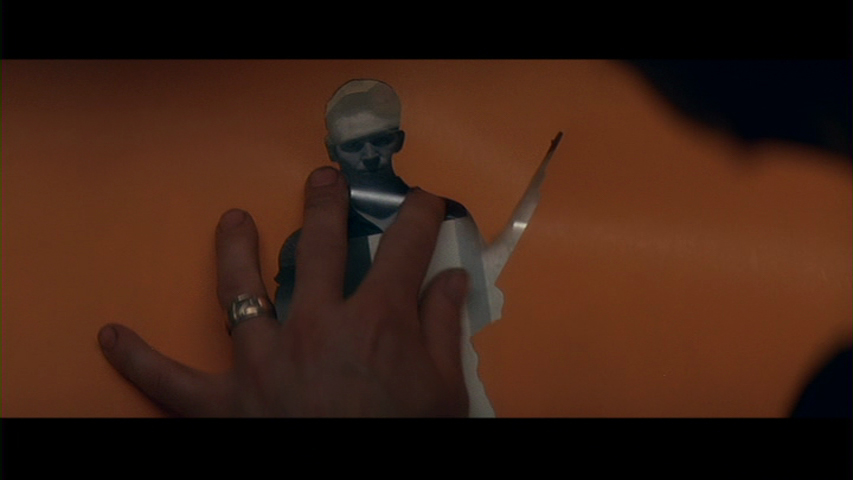

Media images constitute a warped manifold of perception not only because they render events in an incomplete form, but also because they may be deliberately manipulated. The authenticity of historical documents in an age of sophisticated means of image-manipulation becomes a central element of the diegetic narrative of JFK when the photograph of Lee Harvey Oswald that appeared on the cover of Life magazine and “basically condemned Oswald in the public eye” is theorized to be a fake. As Jim Garrison’s staff member describes perceived incongruities in the photograph, the scene is edited together with interpolated shots of the photograph being doctored by an anonymous spook.

Inventing Oswald

The audience is encouraged to wonder at the ontological provenance of this footage of the photo being doctored. The audience is suspended in a state of uncertainty regarding whether these scenes are intended to represent “documentary” footage affirming the “truth” of the photo’s origin, or whether these images simply illustrate what it would look like if Garrison’s staff member were correct in her theory. Extra-diegetically, the audience of JFK is shuttled back and forth between authentic film footage connected to the Kennedy assassination and scrupulously concocted recreations of contemporary documentary evidence. Intercutting actual footage from the Zapruder film with footage of filmed reenactments of the assassination confuses the boundary between what “really happened” and the fictions we have constructed in retrospect, lending an aura of credence to the possibility that the original assassination was itself “staged.”Indeed, the manipulation of images may be the single most important theme in JFK. Garrison freely admits that the basis for the movie’s narrative – his case against Clay Shaw – is too flimsy to stand up to the logical scrutiny of a court trial. For all of the scrupulous presentation of evidence in JFK, the case that Garrison makes against Shaw and the case that the movie makes against the Warren Commission report is not composed of a logical chain of conclusions. Rather, it is summed up by Jim Garrison’s statement to his wife while holding a volume of the Warren Commission report and watching the Martin Luther King assassination on television: “Don’t you think this has something to do with that?”

Don’t you think this has something to do with that?”: the logic of montage

This proposition is not the conclusion of logic, but the conclusion of juxtaposition, the structure of montage. Montage is, of course, the defining feature of JFK’s visual style. As Soviet filmmakers understood, montage is a powerful tool of propaganda, and Stone uses the propagandistic power of montage in the opening sequence of JFK to establish a Camelot image of John Kennedy. JFK utters a historic phrase; cut: he plays with his dog; cut: he laughs on a yacht; cut: he smiles handsomely; cut: he looks pensive in dramatic surroundings. The fragments accrue into the cardboard image of a hero and visionary leader. Montage also shares the same structure as paranoia, a mode of thinking frequently exploited in propagandistic discourse. The opening sequence of JFK shows Eisenhower’s warning in his farewell address about the growing influence of the Military-Industrial Complex. The image of Eisenhower cuts away to a series of shots of military hardware and service members, including the image of a military recruitment poster. This montage of military pride and power, which would constitute a pro-military message in another context, becomes sinister and unsettling against the context of Eisenhower’s words. The semantic effect of montage bypasses reason, engaging consciousness at an emotional level. This is particularly the case when, as in JFK, the pace of the montage is so frenzied that viewers are not afforded the time to reflect upon what they are seeing in one image before it is replaced with the next. One of the reasons JFK can get away with disorienting conscious attention so aggressively yet still be understood as a coherent narrative is because many of the images that gush through JFK’s montages are images with which spectators are already familiar. We do not require much time to process each image and decide what it represents because the figures in these images and, frequently, the images themselves, are drawn from the collective stock footage inventory inside the memory of most American citizens. There is Castro appearing angry, Vietnam footage, and a satellite picture of Cuban missile silos; even if we don’t have time to register each individual image, we respond to a total collection of memories and emotions. The ease with which Stone’s images activate spectators’ personal memories and emotions indicates the extent to which our understanding of the recent past and, indeed, of ourselves, is constructed out of such images. These manipulated and manipulable images constitute an important feature of what we recognize as our fundamental reality. Montage presents a series of clues; the relationship between those clues is not a matter of logic but of intuition – the serial images articulate Jim Garrison’s question, “Don’t you think this has something to do with that?” The narrative as a whole is less a single story than a montage of scenes constructed around different perspectives on matters loosely connected with the assassination. Garrison and Stone are not building a case against Kennedy’s assassins; they are, as one character puts it, “stirring the shit-storm” – compiling a vertiginous montage of questions, factoids, coincidences, correspondences, suggestions, innuendos, emotions, and mysteries, all of which noisily testify to the fundamental impossibility of ever arriving at any final “truth” whatsoever. In lieu of truth, we live in the montage.Moreover, Stone’s montage does not add up according to the standard conventions that dictate continuity in cinematic narratives. When Clay Shaw is answering Garrison’s questions with affable banter, the camera cuts away for less than a second to a shot of Shaw in the same chair lost in silent thought. Such moments, which become more frequent in Natural Born Killers and Nixon (1995), suggest a cubistic approach to dialogue and character. It is as if the filmmaker is offering us a privileged glimpse into another profile of the character’s mood while simultaneously suggesting the inadequacy of any single act of perception to reveal the truth about reality. In the same way that Kennedy had to be maneuvered into the center of a triangulated crossfire in order to be executed, the truth of this execution can only be arrived at by a certain arrangement of points of view, none of which is sufficient in itself. Taken collectively, however, these perspectives might build up a geometric configuration within which “the truth” can be triangulated. Similarly, Garrison’s loose hypothesis that Kennedy’s assassination was the result of a joint conspiracy involving the military, the CIA, the mob, Cuban exiles, the homosexual underworld, LBJ in the executive branch, Earl Warren in the judicial branch, and various defense contractors, oilmen, and bankers represents not so much a legal argument as an impressionistic montage of suspects. The truth is not in any one perpetrator, but in the reticulation of participants, the patterns and relationships. When Stone’s camera reveals Clay Shaw speaking while simultaneously staring silently into space, the juxtaposition implies that the truth of his character is not to be discovered in any one shot alone, but in the interaction between these two contradictory representations. On a wider narrative level, the discrepant montage of perceptual reality bedevils our understanding of “what really happened” during the assassination. In this vein, Stone shows us both the Warren Commission report’s version of Oswald committing the assassination and also Garrison’s version of Oswald calmly eating lunch while the assassination is being carried out by other parties. Similarly, Stone reenacts three different versions of the murder of Officer J.D. Tippett. We see him shot the first time in the sequence by Oswald, then a second time by an Oswald impersonator, and a third time by two men. If the standard motto for protest films or propaganda films is, “seeing is believing,” then in JFK, the act of seeing is turned against itself to undermine credulity. Stone identifies the mystery surrounding the Kennedy assassination with a more intangible mystery at the heart of post-war American consciousness: How can the fragments of postmodern culture be shored up into some form of truth? How can we arrange all these hyperreal images into some shape resembling reality?

Despite the sprawling complexity of JFK’s many subplots, the film

itself is firmly anchored by the character of Jim Garrison, represented as a

greatest generation holdover from the pre-television days. This folksy

anachronism is a credible advocate for the old-fashioned values of truth and

justice. His habit of quoting Shakespeare and the Bible firmly associates

him with Western literary traditions. But the new generation of Americans

– the atomic age generation – is represented by men like Lee Oswald and Dave

Ferrie, men whose personalities are a schizophrenic montage of sorts. The

figure of Oswald in the movie, much like the picture of Oswald that is left to

history, comes across as an irreconcilable jumble of information. A

patriotic defector, a Marxist right-winger, a self-incriminating victim; it is

as if Oswald’s personality had been deliberately assembled out of discordant

pieces of information – surveillance camera photos, travel documents, arrest

records – for the specific purpose of creating a mystery. There is no

overarching logic that explains his personality, just as there is no

master-perspective that could ever capture the totality of the seven fatal

seconds in Dealey Plaza. Oswald’s friend, Dave Ferrie, is similarly

represented as a collage of traits. His apartment is a surreal

accumulation of Catholic vestments, laboratory mice, homosexual pornography, and

other bric-a-brac which constitute his personality. In this sense, Oswald

and Ferrie both represent a new generation of Americans for whom montage is

their natural element and the sole principle of their psychology.

Naturally, these montage-men are deaf to Jim Garrison’s conventional notions of

truth and morality. There is something about the montage-structure – in

either cinema or psychology – that welcomes violence and destruction.

Whereas conventional morality is grounded in the interpersonal affinity and

concern that develops along with a sustained narrative, montage never devotes

enough time to a particular image to grow invested in it or to develop a sense

of concern for it. Indeed, the montage itself is a perpetual destruction

of one image by the introduction of another set of images. The editor cuts

repeatedly, with each new face that crops up mown down by the machine-gun fire

of the editing block. This metaphor is the starting point of Natural

Born Killers, which can be read as a sequel to JFK in its elaboration

on the evolution of American hyperreality.

Natural Born Killers’s Mickey and Mallory are the next generation of the new hyperreal structure of personality pioneered by the likes of Oswald and Ferrie. Natural Born Killers paints a picture of the cultural condition we inhabit in the wake of the ascendency of montage from a cinematic technique to a way of life. In the opening minutes of the movie, black-and-white images of the American landscape cut to black-and-white images from a television changing channels. These establishing images imply that the American landscape into which this movie is transporting us consists not only of photographic images of Monument Valley, but also of video images of “Leave it to Beaver,” Nixon’s resignation speech, and innumerable other equivalent landmarks of the American imagination. When strung together, these images refer to a sense of reality that blurs what exists historically and what is on television, what is shocking and what is banal, as well as what is fictional and what is real. During the opening credits, Mickey and Mallory drive their convertible through a video montage of their true homeland, which is not one of waving fields of grain and purple mountained majesty, but is more accurately represented by a frenzied inter-editing of clips from monster movies, war footage, nature documentaries, atomic explosions, newspaper headlines, and unreadable snippets of violence and confusion, accompanied all the while by a soundtrack that is a similar bricolage of songs, noir poetry, and sound effects.

Driving through the montage-scape

When Mickey flips through channels on a motel room television set, the window behind him jumps from image to image, implying that the world outside the window is identical to the world on the television set. The world around them is aglow with what Mickey refers to as the “manmade weather” of the media. To reinforce further the depth of Mickey’s immersion in this weather, the montage includes purported scenes from Mickey’s childhood. A black-and-white close-up of young Mickey looking innocent and vulnerable as the sound-track indicates that he is being verbally abused by his parents becomes a motif throughout the movie, a “clip” that comes to impressionistically stand for Mickey’s entire childhood. This shot, reminiscent of home movie footage, suggests that Mickey’s memories are themselves preserved in the form of stock footage, and the inclusion of this shot in the window-television screen montage implies that Mickey’s own traumatic memories are embedded in the wider cultural montage of American media culture.

Mickey’s childhood memories edited into the motel room television screen window

Mickey’s murder of the Native American, the murder placed at the chronological and moral center of Natural Born Killers, is triggered by a dream-montage that spooks Mickey into this act of homicide. In this specific instance, as throughout the plot generally, montage and murder are revealed to be companion phenomena. Indeed, the very structure of Mickey and Mallory’s crimes – a series of disconnected and unmotivated acts of random mayhem – constitutes a montage of death, while the victims are mourned as little as the faces condemned to annihilation by the casual remote-control-clicking channel-surfer. In fact, Natural Born Killers switches channels on itself at several points in the movie, as if losing interest or patience with its own story. At the end of the movie, Wayne Gayle has been shot on camera, then killed a second time when the television footage of his death is discarded in favor of other television fare by whomever is holding the remote control of the movie. This inscrutable personage expresses his indifference to Gayle’s murder by casually flipping from the news report of his death to a Coke commercial. The channels then continue to flip through images from contemporary news stories, including the trial of the Menendez brothers, the OJ trial, the Rodney King incident, and the burning of the Branch Davidian compound in Waco. In this final montage, the movie surfs, as we all do, through the quotidian sensationalism and luridness of a culture which is itself a violent montage of celebrity killers. In her critique of the violence of pornography in NBK, Sylvia Chong disparaged Stone’s inclusion of real-world news footage into the concluding montage of his film. “In blurring the line between fiction and fact,” Chong observes, “Stone ends up making the real seem fake rather than making the fictional seem true.”8 Chong describes this effect as a flaw in the film, but if one considers Natural Born Killers within the context of the hyperreal, it is clear that the film succeeds to the extent that it does evoke the impression that the “real” world that Americans inhabit in 1994 is itself a kind of berserk murder montage.

Moreover, as a work of cinematic art, Natural Born Killers splices together the mismatched preoccupations of its two principle auteurs into an uneasy montage. The film’s imperfect synthesis of the conflicting artistic temperaments of Quentin Tarantino, who wrote the original screenplay, and Stone, who adapted Tarantino’s script to his own purposes, reinforces the schizophrenic mood of the film. It is possible for any viewer of Natural Born Killers who is familiar with the oeuvres of Tarantino and Stone to identify which elements of the film owe their genesis to which filmmaker. The dialogue about key lime pie in the beginning of the movie is vintage Tarantino, as is the figure of “Supercop” Scagnetti, Mickey’s gift for telling narrative-style jokes, the prison-escape ploy of duct-taping the business end of a shotgun to a hostage’s neck, and the detail of the Mickey and Mallory narrative that they always leave one victim alive “to tell the tale.” When Tarantino’s characters talk, they talk in sparkling screenplay banter, and when they act, they do so in over-the-top American movie fashion. In Tarantino’s original screenplay for Natural Born Killers, we learn nothing about Mickey and Mallory’s abusive childhoods, Wayne Gayle is not a veteran of Grenada, and Mickey and Mallory feel no guilt for killing a wise old Native American. In short, there is no trace of trauma, history, or guilt in the pre-Stone version of the narrative. Where these themes emerge, we can clearly see Stone at work incorporating a comparatively moralistic sensibility into Tarantino’s gleeful nihilism. Tarantino invents Mickey and Mallory as a legendary pair of icons who are beyond good and evil and who, in owing their entire existence to cinematic representations, share the perfect moral innocence enjoyed by phantasmal entities. Contrastingly, Stone’s revision of Tarantino’s script attempts to embed these filmic creatures into humanistic systems of victimhood and responsibility. The film that results from this convergence of two perspectives, however, does not succeed in subjugating Tarantino’s hyperrealism to Stone’s sociology, nor is Stone’s temperament entirely overwhelmed by the sweep of Tarantino’s creation. Rather, Natural Born Killers juggles both versions of the same story, keeping them in play simultaneously by editing them together in a kinetic and dialogical tension.

The overarching logic of montage also sheds light on the philosophical problems raised in NBK. David T. Courtwright describes Natural Born Killers as a “failed experiment” 9 due to its “contradictory” handling of the problem of evil. Courtwright observes correctly that, at certain moments, the film implies that Mickey and Mallory are evil by nature, that they are, as Tarantino’s title clearly seems to indicate, “born bad,” and so are paradoxically innocent in the same manner as a rattlesnake or a scorpion – creatures whose inherent nature endows them with a license and even an obligation to kill. Other points in the movie, however, clearly indicate that Mickey and Mallory are maladjusted victims of a culture of violence which assaults them both through the supersaturated image-ecology as well as through more physical forms of childhood abuse. Clearly, this schism at the heart of the film is a reflection of the turbulent Tarantino-Stone relationship, Tarantino being largely responsible for the parts of the film that put emphasis on the killers’ Nature, and Stone being largely responsible for those aspects of the film which articulate the “Nurture” argument. That Courtwright regards this schism as a fatal flaw in the movie, however, suggests that he is confusing aesthetic standards appropriate to film criticism with those more fitting for nonfiction prose. Rather than a unilateral explanation of the problem of evil that would safely neutralize the Nature/Nurture debate by choosing one side over the other, Natural Born Killers employs the logic of cinematic montage to dramatize a complex interrelation between these two causal explanations, suggesting that, rather than contradictory possibilities, essence and environment coexist in a troubled interrelation. Stone’s statement in an interview that he conceives of Mickey and Mallory as “the new Adam and Eve in the way that our contemporary society is remaking us into pre-cyborgs”10 combines the argument of environmental causality with an Edenic reference, suggesting that there is an innocence and integrity in acting according to the modes of behavior that are “natural” within a hyperreal environment. Rather than a duality between natural and environmental factors, Natural Born Killers represents a kind of kaleidoscopic swirl of nature and nurture, a vertiginous background of internal and external demons animating and buffeting Mickey and Mallory.

Ultimately, we can make the same evaluation of the moral climate of Natural Born Killers that Baudrillard makes regarding the bombardment of Hanoi: “nothing [is] objectively at stake but the verisimilitude of the final montage.”11 The real power of Natural Born Killers is not in anything it “says,” but in what it is; the individual parts of the film are only significant insofar as they contribute to the total flow of the cinematic experience. Indeed, contradiction itself – between ostensibly contradictory explanations for the problem of evil, between tragedy and entertainment, and between exploitation and critique – is a structural principle of the entire film at its most fundamental level. The anti-hero paradox that gives Tarantino’s original scenario its familiar resonance is the old literary quirk that makes us sympathize with Milton’s Lucifer or Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde. Fictional villains, and especially cinematic villains, possess all of the allure of real villains – their uninhibited freedom, their dangerous charisma, their commitment to self-determination – without any of the corporeal villainy; the magic of fiction scrubs their behaviors of consequence, injustice, or suffering. As long as fiction and reality remained opposite terms, this loophole in the moral imagination remained an aesthetic effect, but in the infotainment era, where fiction and reality have fused into a new semantic ecosystem, OJ, the Menendez Brothers, Nancy Kerrigan, and Bill Clinton himself take on the aura of fictional characters. If we respond to the movie’s cues, we can’t help feeling a little about Mickey and Mallory the same way the enthusiastic crowd outside their trial feels; Mickey and Malory are supercool, way cooler than Manson.

Mickey and Malory are the icons of the new reality: the image ripped out of its context, the innocent killer, the fictional character roaming free across the video prairies of the new manmade nature. Natural Born Killers elicits our own complicity with the cultural tendency it satirizes, blending critique with enactment in a way that collapses the border between character and audience as well as between moralistic valuations of guilt and innocence. Again, Baudrillard is our most reliable guide through this new moral landscape: “Is it good or bad? We will never know. It is simply fascinating, though this fascination does not imply a value judgment.”12 It should not have come as a surprise that the movie was accused of inspiring “copycat” killings. Natural Born Killers virtually begs the audience to cross the perceptual border between the world of the movie and the world of television news. The movie itself is calculated to arouse the audience’s desire to emulate the behavior of its giddy and sexy protagonists. But the very insistence with which Natural Born Killers propagandizes random murder serves a parodic function, provoking insight into how much of cinematic, celebrity, and journalistic culture pushes the same psychological buttons, only without any glimmer of self-awareness. In both raising and ignoring moral questions about violence, Natural Born Killers opens itself up to attacks like Courtwright’s that the movie blatantly contradicts itself, but it also permits the larger and more interesting achievement of allowing itself to behave as a kind of moral mirror. Amoral emotions are aroused so that we may more perceptively subject them to moral scrutiny, while the film’s self-contradiction reveals a self-contradiction within collective social values shared by the spectator.

Following the radical experimentation of Natural Born Killers, Stone returned to a more conventional style of filmmaking. Stone’s next film after NBK, Nixon (1995), borrows techniques of the hyperreal style from JFK and NBK, in particular the montage-effect of using different film stocks to capture the tenor of personal and cultural recollection. At one point, when Nixon visits the Lincoln Memorial, Stone inserts a video montage where the sky should be, in a brief flashback to the window of Mickey and Malory’s motel. At another point, when Nixon is at Love Field on the day before the Kennedy assassination, a brief montage and music cue deliberately echo the opening sequence of JFK. Although many aspects of the movie characterize Richard Nixon as a kind of Mickey and Mallory himself – an essentially amoral hyperreal entity – the main focus of the movie represents him as a troubled individual in the social realist mode. As such, the film shows Stone abandoning his hyperreal period. Although Stone’s Tarantino-esque U-Turn (1997) takes place in a kind of hyperreal twilight zone, Any Given Sunday (1999) and Alexander (2004) show Stone attempting to remake himself as a self-consciously “major” director. Though brief, Stone’s hyperreal experiment represents a fascinating phase in the development of the director’s career as well as a significant contribution to the American cinema and culture of the early 1990s.

NOTES

- Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation. Trans. Sheila Faria Glaser. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 1.

- Contemporary reviews of JFK and Natural Born Killers in the New York Times are representative of film critics who derided Stone’s perceived stylistic excesses: Vincent Canby derides Stone’s “hyperbolic style of film making,” determining that “J. F. K., for all its sweeping innuendos and splintery music-video editing, winds up breathlessly but running in place.” Dec. 20, 1991. Web. June 26 2012. In a similar vein, Janet Maslin writes, “Scratch the frenzied, hyperkinetic surface of Natural Born Killers and you find remarkably banal notions about Mickey, Mallory and the demon media.” Aug 26, 1994. Web. June 26 2012.

- Graham Fuller, “The Unstoppable Stone.” Interview January 1996, 44.

- Baudrillard, 24.

- Oliver Stone, “On Nixon and JFK.” Oliver Stone’s USA. Ed. Robert Brent Toplin. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000), 249-298. 270, 277.

- Oliver Stone, “Stone on Stone’s Image.” Oliver Stone’s USA. Ed. Robert Brent Toplin. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000), 40-65. 53.

- Stone, “On Nixon and JFK.” 278.

- Sylvia Chong, “From ‘Blood Auteurism’ to the Violence of Pornography: Sam Pekinpah and Oliver Stone.” New Hollywood Violence. Ed. Stephen Jay Schneider. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), 249-68. 264.

- David T. Courtwright, “Way Cooler than Manson.” Oliver Stone’s USA. Ed. Robert Brent Toplin. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000), 188-201. 201.

- Stone, “On Nixon and JFK.” 247.

- Baudrillard, 37.

- Ibid., 119

- The author would like to thank Kevin Gardner and Alex Nye for their technical assistance with this article.

Murder and Montage: Oliver Stone's Hyperreal Period by Randy Laist is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License