Headline Hollywood: A discourse analysis of the Variety archive

By Bryan R. Sebok, Ph.D.

Lewis & Clark College

In September, 2010 Variety, the filmed entertainment industry’s oldest industrial publication, announced that their entire 105-year history would be made available in a digital archive. Each daily and weekly magazine would be fully searchable by keyword, and would maintain original advertising and pagination. According to Variety senior editor Timothy Gray,

“(t)he archives consist of 27,000 issues, more than 850,000 stories, 200,000 reviews and countless uses of slanguage and snappy headlines….The archives are intended to be a research tool but also provide entertainment. Some of the stories and advertisements are quaint, others perplexing. But much of it is surprisingly pertinent, such as an item about Disney experimenting with 3D -- in 1933.”1

This article will begin to explore the Variety archive while delineating some key trends in industrial discourse during times of technological change, focusing on the 1950s shifts to widescreen technologies. While the Variety archives offer insight into but one of many possible spheres of industrial discourse pertaining to new technologies, I argue that the archive functions contemporarily as a theoretical intersection of archival discourse, industrial discourse, questions pertaining to digital heritage, and historiographic practices, thereby offering a rich terrain for theorization related to meaning-making in the archive sector as well as the nature and scope of historical inquiry. This project is part of a larger longitudinal assessment of the Variety archives during times of technological change throughout Hollywood history, including the coming of sound, the birth of 3-D, widescreen, the diffusion of color technologies, and the re-birth of 3-D in the contemporary era. As the archives are examined across history, comparative analysis reveals both consistencies and differences in how technologies were made meaningful to readers at the time of publication and came to be integrated into spheres of knowledge according to local historical politics, power, and influence. Here, I hope to suggest the significance of industrial discourse to meaning making surrounding new technologies in a given historical moment while also theorizing how the Variety discourse intersects with existing and emergent meaning making practices in dynamic ways.

While Variety coverage is inevitably but one facet of a broader sphere of experience related to how new technologies were made meaningful in a given historical context, scholars have long relied on this trade publication to make sense of film history and/or to offer directions for subsequent historical research.2

The promotional film below is an example of the range of texts circulating around VistaVision that contributed to the range of meanings ascribed to the technology:

Variety itself has recognized its contribution to the history of cinema, television, and theater and has a history of packaging and re-packaging content, including film reviews and individual issues for sale in other media formats.3 The digital archive is similarly commodified; researchers pay for access on a one month limited basis ($60 for access to 50 issues for 4 weeks) or a full year unlimited access ($600).4 The politics of this commodification is evident in Variety’s own efforts to package history for readers: the site offers access to “featured archives,” a selected collection of Academy Award coverage throughout history and offers “custom options” to remove watermarks and frame editions for collectors. In so doing, the editors/curators of the site suggest the value of particular historical moments over others and encourage a hierarchical understanding of the archive. While the politics of this practice are clearly geared for commercial appeal, their significance to the broader process of historical discourse is noteworthy. The archive situates particular kinds of coverage as commercially viable, leaving other types of stories to the waste bin of history.

Additionally, scholars are just beginning to situate Variety coverage historically, drawing on the newly accessible digital archive to present new insights into stars, historical context, scandal, etc.5 However, the process of theorizing Variety discourse as discourse has been under examined. The ways in which Variety set agendas, established tone and language, situated coverage structurally, and engaged with ideological meaning making suggests that new exhibition technologies (at least) were made meaningful within a sphere of influence that was historically contingent and subject to the dynamics of trade press habitus6. How this coverage is understood contemporarily is subject to the individual historian’s efforts at contextualization, historicization, and theorization of dominant evaluative trends within the press based on available evidence. Contemporary historians make sense of the politics and policies enacted during times of technological shifts, at least in part, via the functioning of the digital archive search mechanisms as much as through the history afforded by the articles themselves. Beginning to recognize the theoretical ramifications of digitization in the archival sector should therefore expand beyond the commonplace discussion of the process of film print digitization. Some of the questions driving this research include: How did Variety reporters frame and discuss shifts in technology? Were shifts in exhibition sector technology (widescreen, Technicolor, etc.) met with expressions of doubt, enthusiasm, or positioned as harbingers of doom? Did trends develop across history related to new exhibition technologies? How and when did a prevailing discourse develop and did it shift in light of industrial maneuvers and adoption of the technology by major theater chains? Did “slanguage” develop and if so, when and under what conditions? And finally, how do we begin to understand the digital Variety archive as a digital source material and as an analog historical tool?

Each of the technologies under consideration were examined by reviewing digital files made accessible through the Variety website during the course of the Summer of 2011 under a faculty-student research grant through Lewis & Clark College and throughout 2012 as the research took shape in its current form.7 In this case, coverage of widescreen technologies were examined through keyword searches for the terms “widescreen,” “wide,” “anamorphic,” the brand names “Cinemascope,” “VistaVision” and “Cinerama,” and followed an evidentiary pattern for shifts, as when a new key term or technology would appear in a given edition, a new keyword search would commence, as was the case with the Tushinsky lens and the term “super-scope” or “C-Scope,” or variations on a brand name, as in “vistavision,” VistaVision,” and “Vista-Vision.” The first 100 articles were examined and coded by researchers in a double blind manner for key words, the appearance of “slanguage,” coded on a scale of evaluative coverage of 1-10 based on pessimism to optimism toward the technology, and further notated for time, type of publication (daily vs. weekly), and author. Additional key phrases were recorded as meaningful quotations that might contribute to a broader understanding of coverage. The articles were then cross coded for reliability and the resulting data was compared. Reliability across the sample was determined to be high and significant.

Widescreen and Technological Discourse(s)

Beginning to investigate the codification of meaning in the Variety archive entails investigating discourses both within an original historical context, with unique politics of signification operating within a given culture, and within a contemporary sphere that is predicated on the realities of access and the functioning of digital search tools. The former begins with the recognition that meaning within the archive is related to the circumstances surrounding the encoding of the technological news in Variety at the time of authorship, and the encouragement of the audience/readership to comprehend meanings related to the technologies as truthful, credible, and rational. For example, the assignation of meaning related to widescreen technologies should be seen in the context of attempts by the authors and/or editors to “win the assent of the audience” to the dominant reading of the article/message.8 Primarily, in the context of writings on widescreen, this amounts to aligning the reader with the “inevitable,” “revolutionary,” and “technophilic” impulses that dominate the coverage. The authors, many of whom are uncredited, seek to cover debuts with enthusiastic aplomb. This does not mean, of course, that the authors would have undertaken a conscious effort to assent to the hegemonic view of technological change, but rather that their work exists within a context that is marked by tensions between organizational values and journalistic ones. In fact, given Variety’s somewhat unique orientation as a trade press, the entirety of all coverage throughout its history should be viewed in this discursive light. The degree to which trade press writers cover stories according to values of competition, professionalism, deadline pressures, etc. vs. concerns over accuracy, and audience reach are inevitably much different from more traditional newspapers. For instance, Variety writers engage with a discernibly more editorial approach to industry events, rarely shying away from hyperbole and sensationalistic appeals. The presumption here being that the efforts of the writers align with the demands of the publication to reach readers who are themselves members of the industry with pre-existing attitudes, beliefs, concerns, and motivations for engaging technology in particular ways.9

For instance, Cinerama, as it appeared in the coverage, was introduced in the following manner in the weekly Variety from October 25, 1950, and subsequently in discussion in the later days of 1952.

This is the “This is Cinerama” referenced in the articles below:

Examples from daily and weekly Variety discussing Cinerama. Click for full size.

What this coverage of Cinerama reveals, outside of the obvious appeals to technophilia, is the establishment of a mode of address and “frame” for the technological discourse. The coverage throughout Variety pertaining to new exhibition technologies across the 1950s appears consistent with a frame that aligns with more traditional news treatments pertaining to “events, not the underlying conditions; the person, not the group; conflict, not consensus; the fact that ‘advances the story’, not the one that explains it.”10

What we see here is an effort made to frame Cinerama as a technology according to the degree of success of the events surrounding its introduction and demonstration, rather than a focus on the generative mechanisms and underlying conditions behind its innovation (particularly the advent and diffusion of television in the American home). Furthermore, the technology is made meaningful by virtue of hyperbolic discourse that links the technology to “revolution,” and all that that suggests for the film industry in light of previous technological shifts including the coming of sound in the late 1920s. The focus on individuals, rather than groups, personifies the stories and links the technology to the executive chiefs at the major studios who align themselves rhetorically with their counterparts in the exhibition sector. These relationships between industrial members from production and exhibition were historically located relative to divestiture of the major theatrical chains by the major studios (ongoing during the moment in question), and that both parties shared financial and industrial interests in differentiating theatrical experiences from televisual ones. Furthermore, throughout the coverage of widescreen technologies, as we’ll see below, the inclusion of dissenting voices as to the viability of a given technology over another suggests the alignment with traditional news reporting on conflict over consensus and the desire to sensationalize as a normative standard within the trade press.

Analyzing discourse structures affords insight into the levels and dimensions of the discourse relating to widescreen technologies. Beginning with “lexical items,” or words that contextually express values and norms in opinion or evaluation, reveals that consistency across the coverage exists. Words repeat across technological coverage, including “dream,” “bonanza,” “new era,” “showcase,” and “revolution.” These concepts combine into “propositions” expressed by surrounding context in the given story. For instance, in an article appearing in the August 5, 1953 Weekly Edition entitled “Release Skeds Stepped Up: Clear Shelves of Flat Pix,” the author describes the shift to widescreen and 3-D pictures and contextualizes “era” accordingly: “It’s figured that the flats may become antiquated as more and more theatres retool for the new era product… it’s estimated that by March, 1954, most of the studios will have cleared their decks of all conventional product.” The propositional structure here expresses opinion by placing exhibitors who have converted to new exhibition technologies on the inside of the trend toward new exhibition technologies and those who haven’t on the outside. “Era” is contextualized as part of a revolution that transcends all facets of the industry and suggests the inevitability of the transition to widescreen products. This lexical item is juxtaposed against “conventional” which here gains a pejorative connotation. In so doing, the author establishes an evaluative structure that aligns with Teun van Dijk’s “ideological square,” emphasizing good actions (conversion) while assigning negative evaluations to those theatres that have yet to “retool.11” Throughout the discourse, local coherence within an edition’s coverage on new technologies is supported by a more global orientation towards the coming of widescreen technologies.

Thematically, the discourse across new technologies beginning with the coming of

sound mirrors this laudatory praise in initial cycles of Variety coverage

of Cinerama. Each time a new technology is innovated, it is

similarly couched in language heralding its potential to irrevocably shift the

industry. Many technologies, though, become subject to

longitudinal shifts in attitude and coverage within the trade press.

For instance, some three years after the initial coverage of Cinerama,

writers were more hesitant in their coverage, pointing to flaws in the

technology, a lack of interest due to limits and the cost of Cinerama

conversion, and the benefits of competing technologies.

Skepticism over the viability of Cinerama was displaced, however, by coverage of

CinemaScope, VistaVision, Todd AO, and SuperScope.

CinemaScope dominated trade coverage throughout 1953 and 1954, as 20th

Century Fox made significant in-roads towards converting the existing

infrastructure to widescreen. Coverage consistently tracked

the conversion and the potential of the format for new revenues following the

premiere of The Robe (Koster 1953). However,

CinemaScope in particular quickly became subject to commodification trends, as

reporters tracked the numbers and the box office, but failed to address the

aesthetic, industrial, and cultural differences afforded by the new technology.

Furthermore, coverage of CinemaScope also became a crucial element to the

conversationalization of discourse pertaining to new exhibition technologies.

This process, within the Variety discourse, is tantamount to the

development of “slanguage.”

Slanguage exists as a discourse phenomenon that establishes insiders and

outsiders. Readers “in the know” understand the derivation of

a given term and may even elicit pleasure from its decoding.

Those outside the group are left without context and denotation to establish

meaning. In the case of widescreen technologies, slanguage

develops as early as February 4, 1953, in an article entitled, “Now Call ‘Em

Flats,” wherein the author (uncredited) encourages the reader through imperative

rhetorical address to shift the lexicon and call all non widescreen/3D pictures

“flats.” While the term doesn’t exactly catch on with the

readership, five articles appearing throughout the calendar year 1953 feature

the term “flats” in this manner. Furthermore, the role played

by slanguage within the readership likely contributes to the overall process of

conversationalization of discourse; the development of terminology pertaining to

new exhibition technologies would have encouraged exhibitor-readers to make

sense of the discourse as more permanent, more viable than otherwise.

Here is an example of a film trailer that further aligns CinemaScope with spectacle, the star system, and sexuality while differentiating the process from 3-D:

CinemaScope, though a major focus of the trade discourse throughout its diffusion into theaters, was subject to the development of slanguage itself; the term “C-Scope” stood in for the full term in headlines and news stories alike. This shortening is a mechanism of editorial convenience to be sure, but it also reflects the alignment of the trade press with the discursive strategies of 20th Century Fox in pushing exhibitors to feel comfortable with the price, the technology itself, and the process of conversion. Yet another prevailing trend within the discourse related to widescreen technologies was the continual focus on conflict over consensus, albeit within a global coherency that favored the technologies as inevitable. For instance, after a period of laudatory praise for CinemaScope, ten articles appear throughout March and April 1954 related to the mandate from 20th Century Fox to install stereo sound equipment to accompany the widescreen image and screen. The authors repeatedly reference contrarians who resist sound conversion, particularly rural theatre owners. This conflict between hesitant exhibitors and the studio reached its peak as Paramount introduced its own widescreen technology, VistaVision, in late April 1954. While the coverage praised the new market entry, the executives at Paramount were careful to encourage the press to resist an all out format battle within the discourse, as evidenced by the headline, “Keep it Wide, But Also Tall: And Speak Well of CinemaScope.12” In dictating to exhibitors at technology demonstrations how Paramount wanted them to contextualize and make meaningful their own widescreen process and encouraging Variety technology writers to orient coverage of the trade press accordingly, executives at the major studios sought to control how and under what circumstances exhibitor-readers, industrial partners, and competitors made meaning relating to widescreen technologies. In this particular case, Paramount sought to maintain good public relations with both exhibitors already converted to CinemaScope and potential clients of VistaVision who shied away from public confrontation and mud-slinging or who were still on the fence regarding conversion. Here again we see an example of insider/outsider discourse within the press related to the construction of hegemonic discourse. Paramount’s President Barney Balaban chose to be gracious in public when it came to entrenched technology rivals, thanking everyone for making VistaVision a reality, including CinemaScope pioneers. His strategic rhetoric belies its potential to support hegemony and the inevitability of technological conversion. By demonstrating restraint and by utilizing inclusive language, Balaban asserts his control over the discourse.

Perhaps not surprisingly, coverage of each of the widescreen technologies introduced in the 1950s follows the pattern of discourse established above, suggesting that the authors and editors at Variety consistently favored new exhibition technologies in their battle to differentiate product while the studios maintained an economic and technological interest in the exhibition sector. Each technology in Hollywood’s broader history of change, whether sound, widescreen, 3-D, or stereophonic sound, is unique in the circumstances surrounding innovation and diffusion. Therefore, coverage of each technology varies according to factors sociopolitical, economic, and industrial-cultural; many share characteristics and trends within the discourse that may be illustrative of Variety’s orientation writ large towards new exhibition technologies.

After a period of extreme optimism within the coverage, typically lasting a few months to just over a year, wherein slanguage may be established and a technophilia predominates, coverage tends to hedge, as complicating factors in the adoption process are revealed. For instance, in the case of CinemaScope, appearing as it did on the heels of Cinerama, was heralded as holding the promise for revolution that Cinerama squandered. Its affiliation with 20th Century Fox seemed to contribute to the coverage, as writers such as Fred Hift, Harold Myers, and Gene Arneel consistently focused on the inter-studio politics behind films being shot and subsequently released in scope. However, the discourse also reflects that these writers, as dramatists on par with some screenwriters of the era, begin to focus on conflict, individual personalities, and squabbles. CinemaScope became, in this period of coverage, a fulcrum point between cities and rural theater chains, between mandates from studios to convert to stereo sound with CinemaScope and resistance from exhibitors. The technological discourse therefore should be seen as dynamic, fluid, dramatized perhaps, and certainly not outside the influence of sensationalistic appeal.

Archival Discourse and the Variety Archive

In order to theorize the archive as a means through which to understand “discourse,” the concept must be applicable to both social theory, including the work of Michel Foucault, and its linguistic application.13 I’d like to suggest, as Fairclough does, that discourse be considered both as a use of spoken and written language and as a form of social practice that is constitutive of meaning making. In so doing, the Variety discourse is linked to social practice that is socially and historically situated while in a relationship to other systems of knowledge. I therefore argue that the use of language within Variety is both socially shaped, by existing attitudes and experiences with new technology generally and exhibition technologies more specifically, and socially constitutive, based on, for instance, how theater owners come to understand new technologies. I argue that each article appearing in Variety contributes toward shaping how widescreen technologies are understood within the readership. The particular circumstances around each article’s publication and its placement and context of publication also contributes to that process of meaning-making. Within this dynamic, coverage engages with and contributes to the creation and maintenance of social identities (for instance stake-holders, innovators, early adopters, rural and urban theater owners, etc. pertaining to widescreen), social relations (or the dynamic attitudes and behaviors of those stake-holders towards each other), and systems of knowledge and belief (attitudes, opinions, and emotions pertaining to the benefits and risks associated with each technological option) such that one element among the three may predominate among the others. It is evident that Variety plays a crucial industrial function in meaning making as well as the creation and maintenance of power within industrial relationships.

A discourse analysis of the Variety archive is aided by the researcher/theorist to integrate Stuart Allan’s (1998) work on discourse analysis in light of the Cultural Studies tradition, Fairclough’s (1995) work on media texts and contexts, as well as van Dijk’s model linking social actors, their cognitive structures, and discursive expression. Allan’s assessment of Stuart Hall’s ‘encoding/decoding’ model (1980) aligns three ‘moments’ of media communication in relation to the naturalization of dominant forms of ‘common sense’ in order to show how news discourse reproduces ideology, social divisions, and hierarchies.14 Allan suggests that the moment of production (encoding), the moment of the text, and the moment of meaning negotiation (decoding), are interrelated to the extent that the discourse naturalizes itself as common sense via framing. For instance, an article from the Weekly Variety dated May 16, 1956 entitled “CinemaScope in Black & White Pends at 20th” that details the flexibility of 20th Century Fox’s policy regarding color vs. black and white productions made for CinemaScope under Spiros P. Skouras reproduces industrial divisions by focusing on the failure of mandates from the company (color and magnetic sound), the cost of optical and magnetic printing, and the ongoing conflict over television by referencing Skouras’ disdain for subscription television. In so doing, the article contributes to the maintenance of the ongoing discourse detailing conflict between the studios and between the film and television industries. An alternative frame could have situated the policy decision of the studio head in the context of successes in the format and the desire for aesthetic variety.

Van Dijk (1988) argues that discourse structures range from micro-level content such as lexical items to macro-level themes expressed indirectly across the discourse. According to van Dijk, the reader assigns coherency at the macro-level and micro-level according to broader systems of pre-existent knowledge. The reader can thereby make sense of the information according to not only what is present, but what may have been omitted or how the item might be understood in light of other contextual happenings. The aforementioned “CinemaScope in Black & White Pends at 20th” therefore becomes meaningful within the discourse via the omission of reference to competing technologies. This can be seen with VistaVision and within the broader context of television distribution, rural theater chains’ conflict over magnetic sound conversion, and the associated contextual knowledge of trends in conversion to widescreen across the industry. Van Dijk further asserts that discourse functions to develop an “ideological square” that divides insiders and outsiders (via editorials and opinion pieces in his research) in order to sway opinion and include the reader (presumably) as insiders. As we have seen, Variety discourse inevitably functions in this manner: the development of “slanguage” and the ubiquitous cross-referencing of industrial phenomena within the publication divides the “insider” readership from outsiders and encourages hierarchical organization of members of the culture. In the “CinemaScope in Black & White Pends at 20th” article, lines like “(h)e pointed out that Metro had announced plans for the first b&w C’Scoper, ‘The Power and the Prize’” serves to include insiders familiar with the slanguage “Metro” for MGM, “b&w” for black and white, and “C’Scoper” for CinemaScope production while excluding those outside of the ideological square.

Fairclough, drawing on the work of Michael Halliday and van Dijk, also devises a tripartite division of discourse components.15 The first is the text or discourse analysis and avails the researcher with information pertaining to the use of vocabulary and syntax as well as structure. The second category examines how discourse practices contribute to the construction of the text, how it is interpreted, and how it is distributed. Fairclough suggests that social practices be analyzed in an effort to reveal how discourse relates to ideology and power. This engagement reveals what Fairclough identifies as two crucial trends in media discourse: commodification (also referred to as “marketization”) of discourse and conversationalization of discourse. While both trends point to the increasingly intertextual nature of media discourse, the former refers to the process by which commercial models of language and media-use encroach on pre-existing discourses (as when advertising language begins to influence feature film story design and the integration of product placement). The latter term refers to the increased informality in language, particularly the news, whereby power and authority are masked in the process of increased stylization and editorialization. While Fairclough locates these trends historically in the 1980s, commodification and conversationalization are themes within the Variety coverage of new exhibition technologies throughout the 1950s. To wit: an article appearing in the April 28, 1954 Weekly Variety entitled “Allied ‘Watchdogs’ Bark Happily at VistaVision Moon,” details the reaction of the Allied States Association, a trade group of exhibitors at odds with Fox’s requirements to convert to magnetic stereoscopic sound with CinemaScope, to the demonstration of VistaVision in New York by Paramount. The article demonstrates that the commodification process herein includes applying a metaphorical frame to an industrial organization in order to be evocative and to provide emphasis through exaggeration. The stylization here is also apparent as the author masks the power position of the subjects via playful analogy.

Speculating on a broader level about the significance of the archive to authority, discourse, power, and meaning-making requires historical and theoretical perspective. While the Variety archive presents a collection of industrial news coverage constituting discourses that reflect part of the historical/technological/industrial discourse at that particular moment, the archive also exists as an archive, and is therefore subject to unique, overlapping discourses pertaining to authority and historiography. For instance, how we understand and theorize the processes of digitization to archives in terms that go beyond the aesthetic, historical, theoretical, and practical implications of digital remastering of film prints affords theoretical insight into the ramifications for researchers of such processes. Film archives typically consist of films, contracts, scripts, memos, advertising, film stills, and corporate documents such as pay slips, intra-office memoranda, and the like. Some archives include personal holdings of particular directors or stars, and are supplemented by letters from fans, between stars, and their personal diaries. Researchers have a tangible experience holding these items, examining them in person within the institutional context of the collection. How that engagement shifts when access is digitized requires further examination and theorization.

Besides individual collections, film archives are often composed of entire studio materials. For instance, the University of Wisconsin, Madison, holds the “official” records for United Artists. Film archives, unlike other historical holdings by museums, are notably contemporaneous in their collections. Instead of relying on found evidence from archaeological digs, film holdings are most often the remnants of directorial or corporate packrats. The holdings of particular museums are selected based on their potential to future generations of scholars and historians. However, the selection process is necessarily purposive on two fronts. First, the surviving family of a given “star” (most often an actor, director, or producer) selects the material they find most suitable to historical countenance. The family is concerned, most often, with maintaining the legacy of the star in question, and therefore may employ a process of editing to the available material. Secondly, the leading archivist at the given institution deems the material suitable and/or acceptable, thereby imposing an institutional legitimacy on the collection. The reputation of the institution, the authority of the archivist, along with the institutional pressure to provide “intrigue” to the archive are no less central concerns in the gathering of materials. As a result, many film archives should be examined in light of these competing agendas, with an eye towards the politics of inclusion and exclusion, and the broader historical evidence available.

When theorizing the Variety archive, however, these questions become more or less displaced in favor of new ones; the fact that the archive is complete in its collection and archived digitally for online access removes some of the politics and exclusionary dynamics behind the catalogue’s materials. Seemingly, the archive establishes authority by virtue of its completeness, thereby implicitly imbuing its articles and editions with historical relevancy and power. However, questions arise that align the archive with broader questions from the field of digital heritage studies, connected to the work of Fiona Cameron, Nina Simon, Herminia Din, Loic Tallon and others who examine information, space, access, interpretation, objects, production, and futures in wide reaching inquiries into the nature of curatorship and provision in light of digitization.16 For our purposes, this field of research raises questions of space and context as it pertains to access to coverage of widescreen technologies. For instance, all of the examples I raise herein were accessed via single page displays from the digital archive, before being examined online and then printed for further examination and coding. Issues accessed “live” (connected to the archive via the internet) through keyword search reveal single pages with stories containing keywords in high resolution quality. Once the page is downloaded to the computer, the resolution becomes highly degraded, such that the stories become virtually illegible. However, once printed, the page regains its clarity and readability, albeit with a large watermark. This process of access, degradation, and restoration is undoubtedly an effort to impose Digital Rights Management (DRM) technologies on the archive to limit piracy. The ramifications for the researcher, though, are several-fold.17 The process of encryption suggests value to the researcher; limits and control suggest scarcity in the marketplace and legitimize the archive’s authority. Furthermore, the very act of encryption aligns the archive with industrial, mainstream content and distribution strategies that place the archive within a broader thematic range of meaning relative to “Hollywood” and legitimacy. Finally, the processes of data management, encryption, watermarking, etc. contextualize the archive relative to ongoing debates and regulation pertaining to free culture, digital piracy, governmental regulation, control, access, etc.18 Therefore, the meanings embedded in the process of digital access to the archive hinge on these circulating macro-level discourses which complement the micro-level engagement with history as represented through the trade discourse.

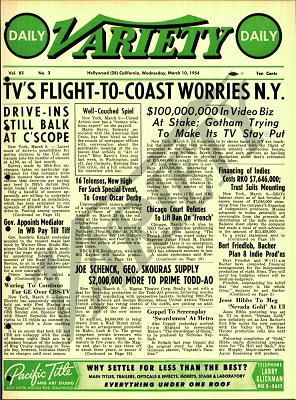

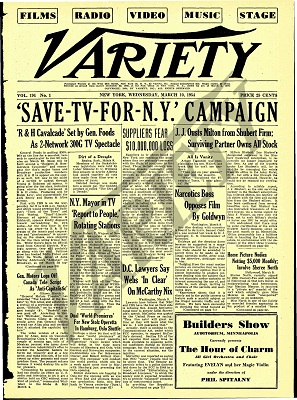

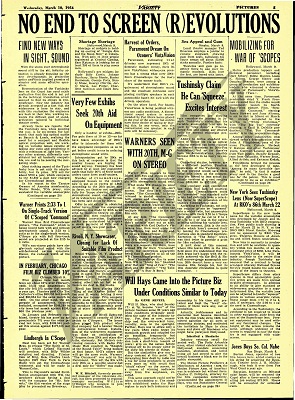

While the contexts surrounding the archive contribute to how it functions discursively as a site of contestation surrounding digital content, the interface and its functionality also contribute to how the archive creates meaning and limits or de-limits historical perspective. For instance, articles may appear within the context of their original pagination, but outside of the context of their original issue in its entirety. How these stories become meaningful in this context, or de-context if you will, is noteworthy. Each page appears via keyword search mechanisms alone, apart from the other pages that would have amounted to the full daily or weekly Variety publication. For instance, the New York debut of SuperScope on March 10, 1954 was given top billing on a technology focused page (page 4 of the Weekly Variety) featuring 10 other stories about widescreen, but viewing that page alone removes these stories from their publication and historical context. The scholar, without the edition in hand, might miss the story on that week’s cover about the $300K television spectacular planned by General Foods in an effort to “Save TV for NY Campaign,” never mind potentially missing entirely both the daily edition’s headline, “TV’s flight to coast worries NY,” and the story on “C-Scope” if the search keyword was limited to the term “Cinemascope.” The function of the search tool therefore limits the nature of scholastic inquiry, forcing the researcher to conduct additional searches in order to broaden the contextual view.

Examples of different search results for Cinemascope. Click for full size.

Missing the connection being made editorially between television technologies, shifting production geographies, and the coming of widescreen would limit the researcher to a somewhat myopic view of history. That said, the results of the research indicate a great deal about how discourse is shaped through a trade publication, and how that publication may structure certain types of language, thus potentially encouraging constituents/readers to think about a given technology in a particular manner.

Conclusion

Many of us are indebted to Variety for its unparalleled coverage of industrial phenomena, ephemera, and slanguistic panache. We draw upon it daily and weekly, online and in print to keep up with the world of entertainment, awards, production schedules and details, and of course, we seek it out to help us understand industrial thinking on new technologies and shifts in industrial structures and practices. Scholars have long sought out Variety for contextual information or historical clues that might lead to discovery in archives around the world. We now have the unique opportunity to consider the Variety archive unto itself as a digital repository of American film culture filled with clues and context, discourse and discursivity. As I have begun to suggest here, the archive needs to be understood accordingly; it exists at the intersection of history and theory and offers us opportunities to unpack the workings of industrial, technological, trade, cultural, star, and myriad other discourses. How these discourses begin to overlap and under what circumstances they shift is rich terrain for future research.

As I have shown, the Variety archive is meaningful in both contemporary and historical/historiographic contexts. As a digital record of a trade publication, it exists as an authoritative account that reflects the corporate/journalistic development of industrial discourse across history. Beginning to contextualize and theorize the digitization of the Variety archive and the ramifications therein, however, requires that we broaden our understanding of digital heritage and the functioning of archival authority. We need to understand the politics of search engines, the decontextualization of articles due to limits in keyword branching, and the ramifications and limits of algorithmic research to the writing of history in the digital era. Digital interfaces that restrict and filter information without transparency limit contextual engagement and understanding.

Discourse analysis of technological shifts throughout the 1950s pertaining to widescreen reveal the dynamic function of language, structure, context, power, hegemony, and social activity. Of the coded articles pertaining to widescreen technologies dating between 1950 and 1954, a full 51% were coded to be “extremely optimistic” in assessing the potential of the given technology. This means that these articles were coded between 8 and 10 on the 10 point optimism scale used by the coders. Conversely, only 14% of coverage fell in the “extremely pessimistic” category, ranging in the scale between 1-4. Of this coverage, many of the articles read as reactionary objections on principle, including such lines as “Drive-ins are the healthiest part of exhibition and just don’t need the fancying up treatment,” which appears in an appropriately titled article “Phil Smith sees no drive-in fancying up” from March 17, 1954. What this reveals about the functioning of the trade discourse historically is clear: technophilic themes engage and combine with opinion and editorial discourse trends to create insider/outsider dynamics that contribute to meaning-making and encourage the march of technological change throughout history.

NOTES

- Gray, Timothy M. “Opening the Variety Vault: Digital version of 105-year archives unveiled Monday” Variety Online Technology News, Variety Magazine, 13 September 2010. Web. 12 February 2012.

- See, for instance, Schatz 1981, 1988, 1999; Cook 2004; Bordwell and Thompson 1979; etc.

- See, for instance, the Variety Film Reviews book series from R.R. Bowker publishing, 1983-1995.

- See https://www.varietyultimate.com/secure/account/?screen=pi1; accessed on October 29, 2012.

- See Tim Gray’s forthcoming (2012) Variety: An Illustrated History of the World from the Most Important Magazine in Hollywood.

- See Bourdieu, P. (1990) Structures, habitus, practices. In P. Bourdieu, The logic of practice (pp. 52-79). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Bourdieu, 1990, p. 54

- I’d like to thank Joshua Cohn, my student research assistant, for his contribution to this project.

- See Morley 1992.

- Data pertaining to readership demographics and circulation figures were not available prior to 1987.

- See Gitlin 1980: 28.

- See van Dijk 1997.

- April 28, 1954: Abel Green.

- See Stubbs 1991, 2003, 2007; van Dijk 1997, 2008; and Fairclough 1993, 2009.

- See Hall, Stuart. “Encoding and decoding in television discourse,” Vol. 7 of Media Series. CCCB, 1973.

- See Fairclough 1995.

- See Cameron 2010; Simon 2010; Din 2007; Tallon 2008.

- See Sebok 2007 for a thorough discussion of Digital Rights Management technologies and the regulation of digital content.

- See Lessig, 2002, 2005; Atkins and Mintcheva 2006; Litman 2006; Gillespie 2009; Wilbur 2000; etc.

Headline Hollywood: A discourse analysis of the

Variety archive by Bryan Sebok is licensed under a

Creative

Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License