On Cinemetrics, Video Essays, and Digital Scholarship – An Interview with Dr. Yuri Tsivian and Dr. Daria Khitrova

Interview, Text, and Transcription: Matthias Stork

Last April, noted film scholar Yuri Tsivian followed an invitation by Janet Bergstrom to deliver two presentations in the Cinema and Media Studies department at UCLA. On April 20, Dr. Tsivian presented his talk “What Makes Them Run, What Slows Them Down: Cinemetrics Looks At Films, Their History And Culture” to an assembly of CMS faculty and students as well as a large group of guests from across campus. His talk inspired a lively debate about the principles of film editing, the use of digital editing databases, and the viability of cinemetrics as a research method.

The following day, he continued his visit with a lecture on “Early Vertov And His Problems”, hosted at the Billy Wilder Theater, in which he illustrated Vertov’s strategies to reconcile the seemingly contradictory elements of his film theory and filmmaking practice. The presentation concluded with yet another engaging Q&A session during which the political dimensions of Vertov’s work were addressed.

Yuri Tsivian has published several books and numerous articles during his career. He is the author of Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties (Pordenone: Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, 2004), Ivan the Terrible (London: British Film Institute Publishing, 2002),

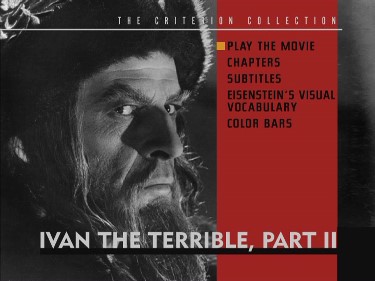

Early Cinema in Russia and its Cultural Reception (Routledge: London, New York, 1994). Furthermore, he is a member of a growing circle of academics who produce work in digital media. The movie measurement and study tool database Cinemetrics is a case in point. The database and software program allows the documentation of a film’s cutting rate. Additionally, Dr. Tsivian recorded an audio commentary for Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (Image 1995), created an interactive learning project on CD-ROM titled Immaterial Bodies: Cultural Anatomy of Early Russian Films (USC 2000), and contributed a visual essay on Eisenstein’s visual vocabulary in Ivan the Terrible to the Criterion Collection’s Eisenstein series (2001).

In between his professional obligations at UCLA, I was able to sit down with Dr. Tsivian and his colleague Daria Khitrova with whom he had collaborated on cinemetrics projects at the University of Chicago. Dr. Khitrova is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor in the department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at UCLA. Both of them shared their thoughts on cinemetrics, video essays, and Sergei Eisenstein’s drawing habits.

Could you explain the concept of cinemetrics as an analytical research tool?

Daria Khitrova: Cinemetrics, on the one hand, is a tool and, on the other hand, a method.

Yuri Tsivian: The method has been used by filmmakers and film observers for quite some time. The first instance dates back to 1913 when someone suggested to start timing shots, to distinguish between a film and a stage play, to clarify the film space and the theatrical space. There was a difference as to how many characters could fit on a stage and appear in front of the optical device of the camera. The timing would also help screenwriters write specific film stories and scenarios. As far as I know, this is first brought up in screenwriting manuals that were published to train freelance screenwriters. Between 1913 and 1916, studios had screenwriters on their payroll but the demand for new films, by exhibitors and distributors, was so tremendous that the regular staff was unable to handle it. Studios thus opened their doors to freelancers who, typically, were unsuccessful playwrights. And they tended to apply their bad habits to film which would result in irreconcilable problems. Studios therefore required them to keep their scenes, more precisely shots, short. The duration was measured in seconds or feet. This is when metrics came into play.

Film scholars started to count shots to distinguish between film cultures and periods. Barry Salt was the first to start publishing these results. He started his work in the 70s. He counted the number of shots in a film, divided them by the length of the film, and came up with the average shot length. Today, in the age of computers, cinemetrics allows us to measure and see how shot length changes over the course of a film.

Could you briefly elaborate upon your current research projects that involve cinemetrics?

Tsivian: One of our projects aims to figure out the dynamics of a filmmaker’s cutting rate strategy across their careers. One project in particular aims to study D.W. Griffith. The project has yet to be completed. More films need to be examined. Another project concentrates on Charlie Chaplin. The idea is to examine whether Chaplin has transformed the structure of comedies that existed before he came on the scene. The traditional model was based on a rapidly cut action comic situation with farcical characters, Keystone cops, bathing beauties, and all that. Fastness was key! Chaplin was not pleased with this model because he had been trained as a stage actor. In his memoires, he wrote that he changed the cutting style and adjusted it to his needs. So he made it slower.

Khitrova: He wanted to shift the focus of the comedy from cutting to acting, to produce an actor-centric movie.

Tsivian: Yes, indeed. In fact, Chaplin did not really change the style for the better. He did not really win the battle. Interestingly, he learned a lot about fastness from his work at Keystone and he incorporated it into his work at other studios, specifically Essanay and Mutual. We have covered the periods at Keystone, Essanay, and Mutual. We have yet to look at a few of his shorts at First National. This is also were he made his first full-length feature, The Kid. And by comparing his feature-length work to shorts, we try to determine whether the length of the films, one, two, three or more reels, factors into the cutting rate. Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t. The question is quite open.

Khitrova: Location also affects the cutting rate. I studied how fast or how short scenes are cut in Chaplin’s Keystone shorts if the action takes place indoors or outdoors. Keystone had a specific set with two rooms, a hall that separates them, and a lobby. Chaplin used it frequently and the different spaces resulted in different cutting rates. I also wanted to comment on the legend that Chaplin was this revolutionary actor who once and for all changed the Keystone cutting style. In his first Tramp film, Mabel’s Strange Predicament, the longest shot in the film does not feature Chaplin but his co-star Mabel Normand.

Tsivian: There is a small difference that I can mention in Chaplin’s favor. His first lobby shot is in fact a few seconds longer than Mabel’s.

Khitrova: But Mabel is present in the shot at the beginning, for just a couple of seconds. So, the shot was filed as Chaplin + Mabel.

Tsivian: That is right, I forgot about that [chuckles]. Another project that we are currently working on involves crosscutting. I am interested in the cutting rates in last-minute rescue scenes in the films of D.W. Griffith.

Since you have been working with cinemetrics, have you noticed a change in your personal film viewing experience?

Tsivian: You start noticing cuts. And you truly begin to appreciate the editor’s work. You pay more attention to the credits and your attention shifts towards the craft of editing. Cinemetrics does not change your life but it changes your perspective on watching movies.

Khitrova: Absolutely. It becomes clear that the essential feature that distinguishes film from other art forms and which defines film as an art in itself is the cutting. My cinemetrics motto is that as soon as you notice these cuts subconsciously, as soon as you notice them all the time, your eye is equal to Dziga Vertov’s kino-eye.

You also developed a user-friendly computer software that allows everyone to measure the cutting rate of a film. It requires you to use your mouse button every time a cut occurs.

Tsivian: Yes, and we have discovered that if you use cinemetrics to determine the cutting rate of a film, you know it a lot better afterwards.

Does cinemetrics require any specific technological know-how or media literacy? Can anyone participate in the project?

Tsivian: Anyone can but not many would. It takes a very special person to develop an addiction to it, to see its value.

Khitrova: There are over 500 participants at this point.

Tsivian: Well, we will never get to the level of Facebook or even Google.

Janet Bergstrom screened your visual essay on Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible in her DVD seminar this year. The essay was produced for the film’s Criterion Collection release. How did it come together? Did you pitch the idea to Criterion? And what did the production process involve?

Eisenstein Criterion and Image of DVD

Tsivian: There is a small group of Eisenstein scholars. It is an international community. Criterion wanted to produce a series of Eisenstein films. One of the producers attended several Eisenstein conferences and recruited me for the project, which was not as much a visual essay as a voice-over commentary. Criterion’s strategy was to look at the film from different perspectives. So, the producers brought in a historian, Joan Neuberger, to look at Eisenstein’s film in the context of Stalinist politics. She provided an alternative voice-over. They also found David Bordwell for Alexander Nevsky.

You become noticeable in academia when you publish and they knew me from the book I had written on Eisenstein [Editor’s Note: Ivan the Terrible (London: British Film Institute Publishing, 2002)]. So, what happened was, there were several recording sessions. The commentary was not off-the-cuff. It was not just an audio commentary. It was a visual essay, a form that I actually prefer. It was planned out. In an audio commentary, you have to ramble on constantly, even during moments when you have nothing to say. It is only filmmakers who can do that well. The approach to the visual essay was different. It involved cutting the voice-over, adjusting it to other visual sources: paintings, for example. It was a great opportunity. Criterion is less commercial than other companies. They are not after the money. They are truly interested in the material at hand. I think the project was discontinued because Eisenstein’s early silent films were either unavailable or existed in too many versions – Potemkin alone has several versions. Now, one of the projects that Daria and I are currently working on involves a Vertov movie, the Kino-Eye in fact, and its two versions. We found a publisher in Vienna who is ready to do two versions of the film. So, you would have both versions available.

Did you provide the sketches and paintings that are featured in the Criterion essay or did Criterion take care of the supplemental materials?

Tsivian: I would like to skip this question, due to copyright issues, which are uncomfortable.

Were you involved in the editing process?

Tsivian: No, I was not involved in the physical editing process. I wrote the script for the essay and described exactly what I would like to see on-screen. Criterion produced the essay. And they did it rather well.

For the Eisenstein video essay, which archives did you use?

Tsivian: Just one archive. Scholarship in Russia is rather centralized. It is in Moscow, the Russian State Archive for Literature and Art. It includes every Soviet archival collection, literature, arts, film. It is a huge depository of books, notes, images; no film copies. The Eisenstein archive is the largest in the building. As a filmmaker, Eisenstein was incredibly demanding and he constantly rewrote and revised scripts, took copious notes.

Khitrova: He produced many drawings.

Tsivian: Yes, lots of drawings. The richness of the archive is so incredible that it took me about five years, give or take, to complete my research.

What was one of the most surprising discoveries that you made during your research?

Tsivian: Well, what struck me most was … well, Daria should probably cover her ears for a moment. I discovered a number of sketches that Eisenstein had drawn for his actors to understand the dynamic of a scene. It was similar to a storyboard. Anyway, there were two penises in the drawing, one short and fat, the other bigger. And Eisenstein, I should say, was a wonderful draughtsman. And it was just a dialogue between two penises.

Khitrova: His notes feature a lot of pornographic sketches.

Tsivian: Yes. He drew them for the actors. One of his cinematographers also had a huge collection of drawings by Eisenstein. And you can find most of them online. But they have also been published in a book.

What exactly was the purpose of these pornographic images?

Tsivian (laughs): He was just a genius.

Khitrova: Plus, he was a manic draughtsman. He was drawing all the time. He just could not contain himself.

Tsivian: I am sure he would be happy to explain his obsession via Freud or Ranke. He was a professed self-analyst.

What was your approach to the essay’s structure?

Tsivian: In terms of DVDs, most “essays” are just voice-overs for the film. You cannot really play with them. At this point in my life, I was interested in something more interactive. For me, a video essay is something that is meticulously constructed and it engages you. I watch it, I argue with its points. A voice-over or audio commentary seems fleeting. You come to a fantastic shot or scene but before you can comment upon it, it’s gone. The eternal contradiction between visuals and aurals is very clear there. So, with the essay, I wanted the viewer to have at least some interactivity. I included chapter breaks so that the viewer could access different parts of the essay. The essay also has color backgrounds that were produced by a designer. I had nothing to do with them. Visually, I often used two slides in juxtaposition. That is a stylistic device that comes from art history. Art historians teach classes using two projectors and two slides and say, well, tell the difference between the two. That is how iconography and iconology were born, by putting two things next to each other.

Is that how you teach at the University of Chicago as well?

Tsivian: Oh yes, no less than two slides, all the time!

Did you have a particular audience in mind for the essay?

Tsivian: Cinephiles is probably the best description for the audience. In theory, you always wonder which audience you should target. But in real life, you realize that you do not think about it very much. You just share what you know. And the language that you choose will alter and calibrate your audience. If you speak in academese then, of course, your colleagues will be disgusted. If you are talking in pictures, then you more or less are using a language that is on a level with Eisenstein’s. He was never interested in targeting film specialists only. He was talking to the entire world with his pictures. And that made his work very clear and interesting. And I think I was trying to emulate that, like making a mini-movie.

Khitrova: Or preparing a class, a lecture.

Tsivian: Yes, that is what we all do.

The video essay is an emerging form of alternative scholarship in the digital age. What do you see as its benefits and/or downsides as an outlet for research findings?

Tsivian: Well, the overall approach to scholarship has not changed. You go to a library, you read. You go to an archive, you watch your movie a hundred times. And the visual essay is an interesting form of scholarship.

Khitrova: But it is not the newest form. There is a company called Hyperkino

Tsivian: Yes, it is a very small company. They produce annotated editions of Russian films across history. They borrow the old tradition of annotating books but, of course, upgraded to the digital level, a multimedia thing.

Khitrova: Essentially, they provide footnotes for films. You watch the film and when numbers appear on the screen, you can pause the film and click on a number. That will then bring up Yuri’s or someone else’s comment on the film.

Tsivian: Yes, in written form.

Khitrova: But they also include other features like video comparisons between the scene and other scenes or other films even, pictures, audio materials, any kind of material. And then you return to the film until the next footnote appears. And Yuri did Eisenstein’s October.

Did the company ask you to provide material for the film?

Tsivian: Yes. I am friends with someone at the company. And I was asked to choose a film and provide a commentary.

Tsivian: Because I have a lot to say about it! (chuckles)

How does your approach to the video essay differ from a written essay or an audio commentary? In other words, why did the video essay format lend itself to the subject matter?

Tsivian: There is always this problem with writing about visuals. Without being able to show the visual. This was a problem two hundred years ago, with art history books. Of course, they published reproductions. It is even harder with films. You can publish a picture, but it still does not move. So, the video essay is the God-given solution for us scholars to create a book which shows you pictures in movement.

Would you consider it the future of film scholarship?

Tsivian (laughs): Wouldn’t you?

Yes, I would. I am a staunch proponent of the video essay.

Tsivian: It is not that film studies will be centered on video essays entirely. Something old stays and something new comes, that is how it is in life. And you choose whichever medium suits you better. I still write essays and I will write a book on cinemetrics rather than visualizing it online.

Khitrova: And I think online journals will be the future of film scholarship. Online journals will be able to publish video essays. But, of course, we still have an institutional problem. Will such publications count towards tenure-track positions?

Tsivian: Yes, well, you can put anything online seems to be the reasoning.

Khitrova: And that is just ignorant. We are still stuck with the written essay.

Tsivian: Well, academia, in its structures and views, is rather medieval. It’s not really open to new elements. But that is a topic for another time. I think it is time to eat now, isn’t it?

Author bios:

Total Archive: Picturing History from the Stereographic Librry to the Digital Database by Brooke Belisle is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.