Media Boundaries and Bullet Time: A Hard Boiled Fan Plays Stranglehold

By Harrison Gish

In 2007 Midway Games released John Woo Presents Stranglehold, a third-person shooter video game positioned as a sequel to Hong Kong filmmaker John Woo’s Hard Boiled (1992), an international hit film starring Chow Yun-fat, Tony Leung, and Anthony Wong.1 Perceived as the epitome of Woo’s spectacular action choreography and as a calling card to Hollywood, Hard Boiled’s success allowed Woo to direct, and Chow to star in, Hollywood action movies, while inspiring Hollywood studios to place successful Hong Kong directors such as Tsui Hark, Ringo Lam and Ronnie Yu at the helm of numerous action films.2 Released fifteen years after Hard Boiled, Stranglehold is an oddity among those video games either adapted from or produced in tandem with blockbuster films, and raises important questions concerning our experience of cross-media properties.3 Here, I investigate my personal fascination with Woo’s cinematic spectacle and how such experience directly informs my incorporation into the world of an enjoyable yet derivative game.4 While films and video games clearly differ drastically in terms of narrative construction, visual modes of address, and subjective experience, I argue that personal involvement with both media forms directly influences our appreciation of and engagement with those games that situate themselves between the stylistic, technical, and interactive boundaries that are understood to divide cinema and video games.

Studying Games, Studying Films

The interrelationship of cinema and video games is a site of critical investigation within the field of video game studies, and a growing body of work focuses upon such cross-media influence. Numerous scholars have applied film studies methodologies to analyze the video game medium within the last decade. Mark J.P. Wolf, Bob Rehak, and Geoff King mobilize theories of spatiality, subjectivity, and spectacle associated with the critical analysis of cinema so as to interrogate the experience of playing video games. Their essays respectively discuss the player’s perception of on-screen and off-screen space, comparatively analyzing classic films and video games through Noël Burch’s theories of cinematic spatiality; the duality of the player’s role as both spectator and participant in the game’s unfolding, utilizing Christian Metz’s understanding of cinematic spectatorship; and the differences between the experience of visually astounding moments in film viewing and interactively overwhelming moments during game play.5 To these scholars, the similarities between cinema and video games, which both exist primarily as visual media, cannot be easily discounted. Nonetheless, Wolf, Rehak, and King are careful to enumerate the differences between the two media, focusing specifically on cinema’s status as a non-interactive6 and abundantly narrative media form whose unfolding the audience cannot directly affect. They then contrast this mandated non-interactivity with games, which require interaction on the part of the player for progress towards a narrative and ludic conclusion.7

Video game narratives have themselves become an important touchstone within game studies, a subject that has provoked a large body of scholarship and has been criticized for its perceived importation of literary and film narrative theory into a field where such questions do not pertain. To Henry Jenkins, video game narratives function spatially. Jenkins argues that video games place a premium on spatial exploration, as players must explore game worlds and the spaces they contain so as to fight enemies, collect coins, or move toward the completion of the game’s objectives.8 As players move through both individual levels and the game as a whole, they activate story elements, such as cut scenes and verbal encounters with non-player characters (NPCs), effectively activating a narrative that continues to grow in detail as spatial exploration persists. First-person shooters, which frequently enforce linear progression, exemplify Jenkins’ understanding of spatial narratives in games. For example, in Call of Duty: World at War (Treyarch, 2008), two entwined narratives accompany the player’s unidirectional push forward through German and Japanese soldiers and the spaces they occupy, namely the personal narrative of the player-character, told through cut-scenes and spoken dialogue, and the grand narrative of the Second World War itself.9

To Britta Nietzel, game narratives are inherently multifaceted, their unfolding less a guarantee than a potential. Depending upon player actions, certain narrative elements may or may not be revealed as the player progresses toward a conclusion. While the designed structure of video games guarantees the inclusion of certain encounters and the narrative information they reveal, players may simply avoid, miss, or ignore other encounters that are not required for game completion. Sandbox-style games such as Grand Theft Auto IV (Rockstar Games, 2008) thrive on just such narrative possibility. Certain players will progress only through the game’s main missions, experiencing nothing more than the story that drives the game toward a conclusion, while other players will spend their time exploring the game’s expansive virtual world, encountering characters who lend breadth to the narrative while not being necessary to the game’s successful completion.10

While the approaches to game studies enumerated above differ wholly, ranging from comparative analysis of video game visuals and the cinematic image to the application of narrative theories towards the game medium itself, all utilize cinema as a reference point when engaging the video game. Such applications of film methodologies and theories to video games has met both criticism and resistance from a variety of scholars who foreground the structured, programmatic, and computational nature of games as the proper focus for a critical inquiry of the medium. To these scholars, the most cinematic elements of video games, specifically game narratives and the cut-scenes through which they are frequently expressed, exist as secondary pleasures of the medium, distracting from the inherent individuality of interactive play. Scholars Jesper Juul and Espen Aarseth both emphasize the potential for interactive play within a digital rule system – a system that continually operates computationally to determine the efficacy of player actions – as the distinctive, defining feature of video games, one that fundamentally differentiates digital games from both cinema and literature. To play games, players must operate effectively within a variable series of constraints that differ depending upon the game played. Such constraints range from prescribed visual perspectives to spatial, temporal, and interactive limitations, and foundationally structure the unique elements of specific games while determining the player’s individual experience.11 It is the “complexity” of digital rule systems that the self-declared ludologists champion, and not the cinematic or narrative elements such systems may contain.

Juul, cautioning scholars against the wholesale application of film and literary narrative theory to video games, writes, “The operation of framing something as something else works by taking some notions of the source domain (narratives) and applying them to the target domain (games). This is not neutral; it emphasizes some traits and suppresses others.”12 While Juul specifically criticizes the application of narrative theories from film and literary studies to video games, Aarseth goes further. Discussing the genre of adventure games, he writes, “The adventure game is an artistic genre of its own, a unique aesthetic field of possibilities, which must be judged on its own terms.”13 Aarseth’s point clearly extends beyond the adventure game to all video games, which differ drastically from cinema and literature in their constituent elements, their finished form, and the experiences individuals have when engaging with them.

Juul and Aarseth, scholars who understand video game play and their inherent pleasures as emerging from individual interaction with a computational rule system, have termed themselves ludologists, overtly foregrounding a methodological approach that valorizes “ludus,” theorist Roger Caillois’ understanding of a mature form of bounded, goal-oriented play. Caillois, seeking to understand the role of games and play in society and culture, introduces the terms “paidia” and “ludus” to demarcate a spectrum of play, ranging from unbounded, wholly free play to directed, constrained, goal-oriented play. While the imaginative play of children on a jungle gym is “paidiac,” a form of play without time limits or overtly expressed objectives, the goal-oriented play of children playing a game of basketball is “ludic,” limited by time, clear spatial boundaries, and a complex rule system. While paidia, to Caillois, intones “spontaneous manifestations of the play instinct,” ludus in its purest form exists as “the pleasure experienced in solving a problem arbitrarily designed for this purpose … so that reaching a solution has no other goal than personal satisfaction.”14 Understood through Caillois’ definitions of play, video games appear highly ludic, foregrounding progression within a system of arbitrary constraints towards a specific goal. An awareness of video game play as a form of ludic engagement, coupled with an understanding that games function only with interactive play, has both spurred the ludology-narratology debate and been applied in a diverse array of game scholarship that pays little heed to this point of contention. The ludologist’s declaration that narrative is secondary to game play and that games are importantly distinct from other media emerges from a legitimate concern that theories of film applied directly to video games without acknowledging the important differences inherent to each medium succeeds only in doing a critical disservice to both.

While the ludology-narratology debate has certainly inspired a large body of video game criticism from both new media theorists and narratologists, to understand this debate as foundational to the field of video game studies in its entirety is inaccurate. Recently, both narratologists and ludologists have declared the debate to be over, not because a solution has been reached, but because accepting the existence of differing approaches to an object of study allows for the growth of diversity, which in turn allows both the field and the scholarship within to progress. Additionally, numerous scholars more interested in understanding how video games function digitally, interactively, spatially, temporally, and culturally – rather than taking polemical stances valorizing the appropriateness of certain methods of inquiry – produce much of the criticism that constitutes and enlivens the field. However, though the ludology-narratology debate may have concluded, and though numerous scholars continue to avoid this divisive issue when analyzing games, it is important to note that cinema and video games do influence each other in various ways that cannot simply be discounted. As Geoff King and Tanya Krzywinska accurately argue, “The boundary between cinema and videogames often appears to be a permeable one, with movements both ways between one medium and another.”15

Expressions of the cross-media permeability between cinema and video games are numerous and diverse, ranging from narrative adaptation and collaborative industrial marketing, to the casting of video game voice actors and the structure of non-interactive narrative moments in games. In terms of adaptation, high concept Hollywood films are frequently adapted into video games that may either reconstruct the film’s narrative in ludic form or may enlarge the diegetic world of the film through further adventures and storylines.16 One of the earliest examples of such cross-media adaptation is the video game version of Star Wars (Atari, 1983), which allows players to progress through levels based on the film’s (George Lucas, 1977) iconic action sequences, such as the climactic X-Wing attack on the Death Star. Today, such adaptations are commonplace, and almost any major blockbuster is accompanied by the release of a video game, as is the case with the recent Thor: God of Thunder (Liquid Entertainment, 2011) released in tandem with the film Thor (Kenneth Branagh, 2011). Extremely successful game franchises are themselves adapted into major motion pictures, a cross-media marketing trend attaining national recognition with Super Mario Bros. (Annabel Jankel and Rocky Morton, 1993) and continuing with movies such as Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time (Mike Newell, 2010). In such films, recognizable game play elements are adapted into spectacular set pieces, as in Doom (Andrzej Bartkowiak, 2005), where the closing action scene is nearly identical to the player’s first-person perspective in the original game (id software, 1993).

While cross-media narrative adaptation between games and films is generally understood as a financial ploy on the part of entertainment conglomerates attempting to exploit popular commodities through ancillary markets, the collaborative marketing of games and films exceeds adaptation alone. Entire film narratives have explicitly marketed both video games and video game consoles directly to consumers, as is the case with The Wizard (Todd Holland, 1989), where the entire narrative progression exists in the service of marketing Super Mario Bros. 3 (Nintendo, 1990), an oft-referenced “secret game” revealed during the climactic competition that ends the movie. The Wizard’s audience watches a play-through of many of Super Mario Bros. 3’s first levels, and game secrets are revealed, such as the location of the game’s first warp whistle. Throughout the film, as the protagonists make their way to Los Angeles and the competition held on the Universal Studios lot, Nintendo games and peripherals such as Double Dragon (Technos Japan, 1988), Rad Racer (Square, 1987), and the Power Glove are played within the movie, discussed in detail through dialogue, and focused upon through lavish close-ups.

While The Wizard is certainly an emphatic example of game marketing within cinema, pitching games to film audiences continues in far more subtle forms today. In the recent alien invasion action film Battle: Los Angeles (Jonathan Liebesman, 2011), the sole billboard standing in a decimated west Los Angeles advertises Resistance 3 (Insomniac Games, 2011), a game concerning alien invasion distributed by Sony, the parent company of both Insomniac Games, the developer of the game, and Columbia Pictures, the studio which released the movie. While in-game marketing of films is far less frequent, advertisers continually market games as approaching the cultural status, narrative heft, and visual spectacle of cinema, as is the case with the marketing of Uncharted 2: Among Thieves (Naughty Dog, 2009), for which television advertisements featured a young woman mistaking the video game her boyfriend plays as being a Hollywood blockbuster.

The intersection of cinema and video games is not limited to adaptation and blatant references, however. The unique structures and rhythms of each medium—the ways in which cinema and games convey information to viewers and players—have also traversed the boundary that divides these media. Video games frequently utilize non-interactive sequences, termed cut-scenes, that operate through cinematic conventions, a narrative technique popularized in Final Fantasy VII (Square, 1997), a game advertised entirely through its cut scenes and not through sequences of actual game play. Initially termed “cinematics,” cut scenes have become a form of narrative expression all their own, resembling cinema less as both game technology and games’ expressive potential have matured. Today, the non-interactivity of cut scenes is not guaranteed. For example, players must perform actions at a moment’s notice during cut scenes in games such as Assassin’s Creed II (Ubisoft, 2009) and Resident Evil 4 (Capcom, 2005). Much of the recent Heavy Rain (Quantic Dream, 2010) questions the status of the cut scene as existing at a remove from game play, as the majority of player action occurs during seemingly “cinematic” sequences.17

Cinema’s influence on games is, however, not limited to the editing of pre-rendered narrative exposition. Established screen actors have lent their voices to major games, as with Ray Liotta voicing the player-character Tommy Vercetti in Grand Theft Auto: Vice City (Rockstar North, 2004), a casting decision that draws upon Liotta’s cache as the star of Martin Scorsese’s seminal gangster film Goodfellas (1990). Video games have appeared in the mise-en-scène of films in order to place characters culturally, as in The Princess Bride (Rob Reiner, 1987), where the first onscreen image is of the baseball video game Hardball! (Accolade, 1987), situating Fred Savage’s character as a middle class suburban youth with little time for literary fantasy. Finally, film narratives deliberate the social and cultural repercussions of video game play in dystopian science fiction contexts, such as with The Lawnmower Man (Brett Leonard, 1992), The Thirteenth Floor (Josef Rusnak, 1999) and Gamer (Neveldine/Taylor, 2009), films which depict worlds where the boundary between video games and reality blurs to the point that the difference between the real and the virtual can no longer be identified.18

It is near this critically and industrially constructed boundary between films and video games that John Woo Presents Stranglehold exists, a unique game that itself intertwines many of the categorizations of film and video game hybridity mentioned above. Unlike the average film-to-video game adaptation, Stranglehold was released fifteen years after Hard Boiled, approximately a decade subsequent to the late-1990s heyday of Hong Kong directors and actors producing, directing and starring in high budget Hollywood cinema. Neither retelling Hard Boiled’s narrative ludicly nor featuring an alternate narrative set temporally simultaneous to the film’s events, Stranglehold instead continues the story of Chow Yun-fat’s trigger happy cop Tequila, taking him from Hong Kong to Chicago as he pursues an international group of criminals. In so doing, Stranglehold is positioned as a video game successor to Hard Boiled, a literal sequel that recasts the successful elements of the film in new settings, doubly so in that Tequila takes on gangsters in such places as the slums of Kowloon and the Chicago Natural History museum (action venues not explored in Hard Boiled) and that the narrative continues to unfold in a new medium. In Stranglehold, the Tequila player-character is voiced by and motion-captured from Chow Yun-fat, and Woo, who had a small yet meaningful part as a bartender to and mentor for Tequila, is also motion and voice-captured, appearing both in the game’s cut scenes and in the game’s menu. As well, the game was advertised as a John Woo production, as the director collaborated with the game designers, advising the narrative and cut scene development. As such, while first and foremost a video game, John Woo PresentsStranglehold positions itself as hailing from cinema. Stranglehold is not a neutral media object; it overtly appeals to fans of Woo’s films and constantly references Hong Kong cinema, both through its narrative and its dynamic, interactive structure. To understand my own experience playing Stranglehold, I must first explore my experience of Hard Boiled.

Taking Hard Boiled Personally

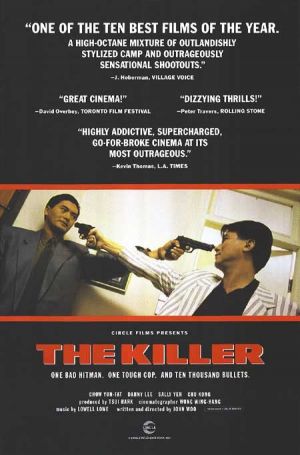

My first encounter with John Woo’s films came in Cambridge, Massachusetts during the early 1990s. Standing in the middle of summer outside The Brattle Theatre, one of the great art- and revival-houses on the east coast, I saw a poster for The Killer (1989) and was immediately intrigued. Long a fan of action cinema, my experience with such films had been, up until that moment, decidedly Western. The poster promised something I had yet to encounter, a direct form of action choreography that would be experienced as an assault, both between the films’ two protagonists (Chow Yun-fat as the titular assassin and Danny Lee as the inspector hunting him) and upon the audience itself. To call the poster ‘in-your-face’ today seems doubly appropriate.

Image 1: A poster for The Killer foregrounds John Woo’s penchant

for constructing

sequences of spectacular violence.

My first experience watching John Woo’s cinema came several years later (at an age when my parents gave me carte blanche to rent whatever I chose from the local video store), after the director had begun making his mark on Hollywood with Hard Target, a 1993 Jean Claude Van-Damme film set in New Orleans that borrows liberally from The Most Dangerous Game (Ernest B. Schoedsack, 1932), and Broken Arrow, a 1996 John Travolta and Christian Slater film where the pair fight over nuclear arms in the American West. The Killer had been rented from the video store’s minimalist ‘Foreign’ section, and so I instead chose Hard Boiled, whose videocassette box promised stylized action, astonishing stunt choreography, and a man plunging into the urban metropolis of Hong Kong while wielding two handguns.

Image 2: The video box art for Hard Boiled, juxtaposing

the trigger-happy cop Tequila

with the urban milieu of Hong Kong.

From the teahouse gunfight that opens Hard Boiled to the violent and spectacular extravaganza that concludes the narrative—an action scene that crescendos masterfully, contained within the space of a hospital where ruthless gun runner Johnny Wong uses the morgue as a personal armament warehouse—I was thoroughly absorbed and utterly astounded. At a time when it seemed important to be able to readily identify my favorite film within any given genre, Hard Boiled immediately became my favorite action film, a choice that I thought situated me as being both hardcore (in that Hard Boiled featured the most astounding gunfighting I had ever seen on either film or magnetic tape) and worldly (in that Hard Boiled was decidedly international fare, far different from the Hollywood films my friends and I had grown up watching). I viewed Hard Boiled countless times over the next several years, persuading numerous friends to engage a film I pitched as an action masterpiece. Working at a video store in Brookline in 1998, I suggested Hard Boiled with zeal whenever customers asked me for my action recommendations, an experience that left both them and me disappointed (store patrons criticized the film for containing too much violence, being incomprehensible, and being in Chinese, criticisms I cannot help but believe are interrelated). Their critiques only strengthened my belief that Hard Boiled was a masterpiece, and that I was a master viewer for being aware of its power.

Three moments of Hard Boiled stood out to me as essential viewing for any action fan, a claim that I still hold to today. Hard Boiled opens with a teahouse gunfight, during which Hong Kong cop Tequila, pursuing an arms dealer, utterly destroys the teahouse interior and slides down a handrail so as to shoot a gangster who is killing innocent patrons. The sequence culminates in what I still think of as one of my favorite cinematic images, with Tequila spitting out a toothpick before executing the arms dealer, whose blood then splashes over Tequila’s face, which has been previously covered in flour (the execution itself occurs off-screen).

Image 3: Tequila executes a criminal at the

conclusion

of Hard Boiled’s opening

gunfight.

Halfway through Hard Boiled, Tequila raids a warehouse in which two criminal organizations are already engaged in battle. Rappelling in from the warehouse ceiling, Tequila appears to fly through the air, killing countless criminals with his pump-action shotgun. Upon touching down, Tequila is by no means restricted to the ground floor of the warehouse, and instead leaps over motor vehicles as he uses his shotgun to obliterate several motorcyclists, yielding improbably large explosions, accentuated through Woo’s use of slow motion.

Image 4: Tequila flies through the air, dispatching

both villains and motor vehicles with

his shotgun.

In the film’s closing action scene, a forty-minute set piece that is really multiple action scenes strung together into an overwhelming spectacle of stylized violence, Woo employs the tracking shot masterfully. Following Tequila and his undercover partner (Tony Leung) through hospital hallways, Woo transitions into and out of slow-motion frequently, as the pair round corners, switch positions, and eventually enter a hospital elevator that takes them to another floor.

Video 1: An incredible tracking shot from Hard Boiled’s epic, excessive conclusion.

In addition to the exemplary scenes mentioned above, Hard Boiled also includes numerous tropes associated with John Woo’s oeuvre, such as the iconic image of two characters locked in a firearm stalemate, recalling The Killer’s poster, and a visual and narrational doubling of the film’s two protagonists, both perfectly expressed in the following image.

Image 5: Chow Yun-Fat’s Tequila faces off against

Tony Leung Chiu Wai’s undercover

cop Tony.

The fascination I experienced with Hard Boiled is by no means mine alone. The spectacle on display has astounded YouTube contributors, journalists, film critics and theorists alike. Stephen Teo describes the climactic fight scene that ends Hard Boiled as being “hysterically excessive” and “breathtaking.”19 YouTube video bloggers are less restrained, declaring the closing hospital fight the “Best Action Scene Ever Filmed.” Though film theorist and historian David Bordwell criticizes Hard Boiled for being “frankly designed as a portfolio film for Hollywood,” he nonetheless utilizes a shot-by-shot breakdown of the teahouse gunfight’s conclusion to exemplify what he understands as the “pause/burst/pause” editing and choreographic rhythms of Hong Kong action cinema.20

To Bordwell, Hong Kong cinema “embraces a circus aesthetic, mixing amusement, astonishment, and a delight in farfetched feats,” embellishing “effortless grace and geometrical precision,” resulting in a “clarity of action” absent in Western action films prior to the importation of Hong Kong filmmakers to Hollywood. This clarity “is furthered by one paradoxical quality. These scenes seem fast because they make a calculated use of fixity. They seem constantly in movement because they incorporate stasis.” This technique is on display in Hard Boiled, where the execution of the arms dealer that ends the teahouse gunfight displays moments of stillness along with moments of precise movement. Bordwell writes,

"In the gun battle that opens Hard Boiled ... Tequila has raced into a kitchen in pursuit of a gangster who has shot his partner. The gunman lies on his back on the floor, firing. Tequila dives onto a tabletop, rolls across it through a cloud of flour, and leaps off. Four shots map his rightward and downward trajectory. In the last of these, he glides across the frame to come to a sudden halt, the pistol to the gunman’s head. There follow three close-ups in which the killer and Tequila stare at each other, motionless and silent. Tequila’s dive consumes a second and a half; the unmoving exchange lasts nearly as long. This comparatively long pause accentuates the next two movements, executed in quick succession: Tequila contemptuously spits out his toothpick and executes the killer, spattering blood across his own bleached face."21

Though both the opening teahouse battle and the later warehouse gunfight are rapidly edited, even the tracking shot that occurs during the hospital shoot-out adheres to the “pause/burst/pause” aesthetic. In this final action sequence, violence is not continual. As Tequila and Tony make their way through the hospital corridor, they frequently pause to reload their guns, exchange exclamations, and discuss Tony’s shooting of a fellow police officer in a moment of recklessness. These pauses are embellished even further through Woo’s use of slow-motion; as the characters switch positions, the film itself literally slows, foregrounding both this spatial exchange between the two protagonists and the shoot-outs to come. As the film returns to normal speed, the violence, already astonishing, is rendered even more impactful, appearing accentuated due to its temporal difference from the moments of slow motion. A double “burst” of action seems to occur, astonishing the viewer through the over-the-top violence on display at the very moment the film returns to an approximation of real time.

While I did not read Bordwell until college, during my high school experience of Hard Boiled I understood the processes he describes intuitively. The editing and choreography of these sequences were affective in a way that the shootouts in Die Hard (John McTiernan, 1988) and The Terminator (James Cameron, 1984) were not. My fascination with Hard Boiled as a masterpiece of action cinema quickly went beyond this film alone. Throughout college and graduate school, I have attempted to investigate Hong Kong cinema’s multifaceted history, exploring classic wu xia cinema, gunplay films that never made it to the United States, and the exemplary work of Johnnie To. I took Hard Boiled personally, allowing it to overwhelm and influence me as a spectator, as a scholar, and, eventually, as a video game player.

Incorporating Hard Boiled into Stranglehold

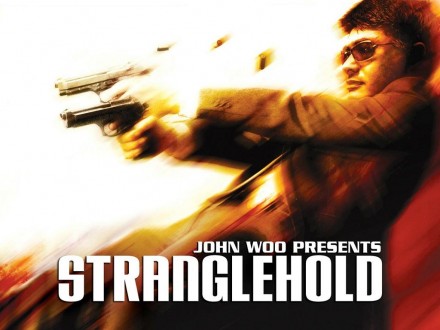

My first encounter with Stranglehold was significantly different from my first encounter with John Woo’s cinema. Standing in a gas station on Santa Monica Boulevard in West Los Angeles, I looked up to see a large billboard advertising a video game, a rare occurrence in 2007, similar to the following image.

Image 6: The billboard and box art for Stranglehold.

I quickly noted Woo’s name above the game’s title, Chow’s face, and the positioning of two handguns, similar to the image that had invited me to experience Hard Boiled years prior. I was both astonished and perturbed, thrilled that one of my favorite movies was getting a video game treatment while apprehensive that such a game could in no way approximate my experience with the film on which it was based. This apprehension overwhelmed my interest, and I put off purchasing the game for four years (I did not own an Xbox 360 for another two), until Amazon strategically synthesized my purchasing history and seemingly advertised the game to me specifically, flaunting its less than ten dollar asking price. Unable to resist adding such a comparatively inexpensive game to my collection, a game for which I was absolutely the target demographic, I ordered it and decided to see whether Stranglehold would live up to my relatively low expectations, or surprise me by exceeding them. In contemplating such possibilities, I forgot that my own personal experience with Hard Boiled would distinctly influence my appreciation of the film’s video game sequel.

As a media experience, I find Stranglehold significantly less compelling than Hard Boiled. While Woo’s film is, to me, an exemplary manifestation of Hong Kong action cinema (and cinema generally), many video games have astonished me far more than Stranglehold. Max Payne (Remedy Entertainment, 2001), to which Stranglehold bears more than a few design similarities, is a far superior game, with a captivating storyline, a seductive, noir-ish, at times horrific aesthetic, and an appealing anti-hero as its player-character. Stranglehold is not a “bad” game per se, but simply a game that does little to stand out from other contemporary third-person shooters. Labyrinthine and frenetic are the best terms I can think of to describe the game’s aesthetics and play structure. A consistent tone is absent from Stranglehold; while play mechanics remain the same throughout, the levels seem disconnected and random, linked together through uninspiring cut scenes. The narrative is the caliber of one of Woo’s ill-fated American television pilots, and while the traversal from the neon lights of Kowloon to the drab interiors of the Chicago Natural History Museum certainly makes the settings seem disparate, this also lends a discontinuity to the game’s virtual world. At least, this was my initial impression of Stranglehold.

Yet the more I played Stranglehold, the more I found enjoyment during play, not because the game itself improved, but because during rare moments of heightened activity, when the game demanded that I be extremely attentive to the numerous NPCs swarming the Tequila player-character I controlled, I found myself as overwhelmed as I was during my viewing experiences of Hard Boiled. In other words, there were distinct bursts of play when I felt as if an action scene from the film was unfolding in front of me. As such, my experience playing Stranglehold corroborates Geoff King’s understanding of spectacle’s function within video games, which frequently inspires “a sense of assaultive impact and sensation” in the player.22 Spectacle, moments in both games and films of excessive “scale, detail [and] texture,” exists to provoke both “admiration” and “astonishment” in players and viewers, who marvel at both the scope of what is depicted on-screen and the technical complexity necessary to achieve such grandiosity.

To King, two forms of spectacle operate in games and films: a “contemplative” spectacle that is massive in scale and emphasizes the breadth and beauty of a particular space, and an “assaultive” spectacle that revels in “action” and “destruction.”23 Though both Hard Boiled and Stranglehold more frequently emphasize the latter, foregrounding scenes of intense violence featuring structures and bodies decimated through explosions and gunfire, the film and game achieve the effect of a spectacular assault differently. While the interactive virtual world presented in Stranglehold does not in any way approximate the look or feel of Hard Boiled, the demands the game placed upon my attention and the way I felt overwhelmed by the spectacle on display did approach the affectivity of the film’s astonishing bursts of action. The pauses between these in-game moments were, however, far more protracted than in the film and, as I realized where true pleasure lay for me within the game, I began to strategize. I attempted to place my player-character in situations where such interactive and visually spectacular moments would again occur. In effect, I began to work towards an approximation of my Hard Boiled experience through play.

Video 2: In Stranglehold, the player must actively run head-long toward NPCs so as

to approximate Hard Boiled’s spectacular action scenes, activating what Geoff King

terms “assaultive spectacle” through play.

As a game, Stranglehold resembles Max Payne distinctly, far more so than it resembles Hard Boiled, especially in its inclusion of player-activated slow motion within a third-person shooter. Max Payne altered the sub-genre of the third-person shooter in that it allowed the player to engage “bullet time,” during which the player-controlled Max leaps forward as the game enters into a slow motion that affects the surrounding environs, the oncoming enemies, and the player-character’s trajectory through space.24 What remains unaffected by this temporal attenuation is the ability to aim and fire. While the body of the player-character slows, the torso swivels at regular speed, allowing players to take aim and fire upon NPCs who are momentarily incapable of returning fire as quickly. Max Payne’s manual and box art specifically reference John Woo’s cinema as both an influence on game design and a goal of game play; players, it is hoped, will feel as if they are playing within a John Woo film when they play not only Stranglehold, but Max Payne as well.

Interestingly, the comparison of John Woo’s cinema to Max Payne’s “bullet time” is slightly inappropriate. “Bullet time” refers far more accurately to the digital cinematography of The Matrix (The Wachowskis, 1999), where actors, performing stunts in front of green screens, were simultaneously filmed from an array of cameras that surrounded them. This unique approach to digital filmmaking allowed editors to slow down moments of physical action while transitioning between cameras sequentially at varying speeds, resulting in the feel of a tracking shot in which time had either stopped or slowed while the camera continued to move. In The Matrix this stylistic flourish is an external reflection of character interiority; able to control the digital world that is The Matrix, Neo (Keanu Reeves) and his cadre of freedom fighters are capable of manipulating the temporality and spatiality of their surroundings. Of course, Woo’s influence on The Matrix cannot be discounted, yet his use of slow motion varies considerably from The Matrix, Max Payne, and Stranglehold. In Woo’s films, as can be seen from the Hard Boiled clip above, slow motion does not give the characters an advantage over their enemies. It is specifically stylistic, enhancing, as Bordwell discusses, the potency of the forthcoming action. In Max Payne and Stranglehold, slow motion becomes functional, allowing players to carefully aim targets at their opponents and execute them with precision.

Video 3: In Stranglehold slow-motion is functional, allowing players to both leap past

and take aim at NPCs while their movements are slowed. The player’s ability to swivel

and aim during play remains unaffected.

Another form of “bullet time” exists in Stranglehold as well. Collecting origami pigeons gives the player the ability to zoom in on targets and shoot at particular body parts, such as the heads, chests, and even crotches of oncoming NPCs. As opposed to firing a hail of bullets, one bullet is fired, resulting in a very brief non-interactive cut scene in which the virtual camera trails the bullet in close-up as it flies rapidly toward the targeted appendage. The virtual camera then transitions to a medium shot of the NPC being hit, blood spurting from the point of contact. To my knowledge, Woo has never featured close-ups of bullets flying through the air in his films. The technique instead may be credited to Woo’s contemporary Ringo Lam, who employed close-ups of travelling bullets in Full Contact (1992), a Hong Kong gunplay film also starring Chow Yun-fat. Clearly, Stranglehold’s functional game play elements are not only indebted to Hard Boiled or to Woo’s cinema alone, but to other films that exemplify 1990s Hong Kong and Hollywood martial arts and gunplay cinema.

Stranglehold differs from Hard Boiled not only temporally but also spatially, in terms of the perspective on the unfolding action the game provides the player. The game as a whole distinctly resembles Hard Boiled’s hospital hallway tracking shot, with the virtual camera positioned above and behind the player-character, much as Woo’s camera lingers behind Tequila and Tony as they decimate criminals and the hospital itself, moving through constrained corridors and proceeding literally from level to level. The lengthy tracking shot is not a normative Woo motif, standing apart from the other action scenes that appear throughout the film. As Bordwell notes, the editing in Woo’s action sequences is generally rapid; in the teahouse gunfight’s conclusion, the longest single shot lasts three seconds. The continual presence of Stranglehold’s virtual camera, fixated on the player-character Tequila, both literally and figuratively distances the player from the ensuing action in a way that Woo’s films do not.

The rapid transitions between perspectives in Woo’s action sequences have the effect of placing the viewer within the ensuing violence. The continual spatial relocation of Woo’s camera, associated with the protagonists only during the hospital hallway gunfight, never attempts to convince the viewer that they are Tequila or Tony. However, Woo’s technique does an outstanding job of overwhelming the viewer with a bombardment of bullets, explosions, and bodies, as well as an equivalent number of perspectives on the action, so that the violent barrage depicted in the film becomes a visual barrage upon the viewer. In Stranglehold, the player is comparatively withdrawn. The stability of the camera and the oncoming NPCs’ focus on the player-character, and not on the player, have the effect of placing the player at a remove, continually reminding the player of the barriers that exist between them, the onscreen virtual world, and the action they control within.

Of course, the most important difference between Stranglehold and Hard Boiled is that Stranglehold is a video game and Hard Boiled is a film. Attempting to replicate Woo’s filmic editing style would be nonsensical for a video game. A barrage of cuts displaying multiple viewpoints on the unfolding action would make Stranglehold truly unplayable and undercut the generic affiliations of the third-person shooter. Also, including Max Payne’s “bullet time” as a core mechanic of game play allows players to feel as if Stranglehold is similar to other popular video games while it also approximates Woo’s cinema. Though action is non-stop – there are very few pauses within game play – those moments where I activated “bullet time,” leapt through the air, and opened fire on approaching enemies made the crumpling of their bodies to the ground in real-time all that much more satisfying. While differing totally from the pause/burst/pause structure Bordwell finds within Woo’s film, the effect of “bullet time” on my play experience yielded a complementary result. Through pauses, I performed complex actions with a precision that mimicked the grace and exactitude of Woo’s action choreography.

However, the moments of true pleasure in Stranglehold for me as a video game player and a fan of John Woo’s cinema came in the rare moments when I felt I had achieved a feat that approached the over-the-top grandiosity of Woo’s action scenes. Killing a few villains in the slums of Kowloon left me unsatisfied, but flying across a display case in the Chicago Natural History Museum while dispatching gangsters encircling my player-character while snipers rappelled down from the ceiling above, left me enthralled, as I beheld an excessive spectacle on par with a great Woo action scene. As Stranglehold progressed, increasing in difficulty and throwing ever more NPCs in my direction, this feeling of transportation into the game occurred more frequently. As I grew increasingly accustomed to game play, I no longer desired to simply destroy NPCs. Instead, I attempted to do so in a way that was affectively similar to watching Hard Boiled’s hospital hallway gunfight. In this way, I found myself experiencing what Gordon Calleja discusses as incorporation, “a shortening or disappearance of distance between player and game environment.”25

While playing Stranglehold, I never truly became immersed in the game’s virtual world. Exceptionally aware that I was playing a game based upon one of my favorite films, I at no point found myself mistaking the virtual world of the game for the world I inhabited, and at no point did the interface between the actual and virtual truly seem to disappear. Stranglehold, with its constant onslaught of enemy NPCs, required me to react rapidly while being strategically aware of how much “bullet time” remained, and as such was simply too difficult and too complex a game for me to lose myself in entirely.26 As Stranglehold continually hails a film with which I have much experience, I am constantly reminded when playing that this is a play experience distinct from both the film and the actual world surrounding me. However, as I manipulated Tequila during moments of intensified play, I began to experience simultaneity between the actions I performed upon the controller and the actions my in-game surrogate performed onscreen. Approaching the spectacle on display in Woo’s cinema through my own actions, creating and witnessing an overwhelming barrage of explosions, bodies, and bullets, I sat astounded, much as I do when watching Hard Boiled. In these moments, both in Stranglehold and in Hard Boiled, I do not believe myself to be within the virtual world depicted in front of me, but I do tend to forget myself slightly. The attention the game and film demand during their most spectacular action sequences, and the awe these moments inspire, similarly astound to the point that my awareness is targeted less at myself and more directly towards the virtual world beyond the screen.

Calleja carefully discusses this distinction, proposing six frames through which players may become incorporated into games as “conscious attention” to the game and one’s actions within its virtual world give way “to internalized knowledge.”27 These frames include tactical involvement, “interaction both with the rules of the game and with the broader game environment;” performative involvement, “game piece control in digital environments, ranging from learning controls to the fluency of internalized movement;” affective involvement, “the cognitive, emotional, and kinaesthetic feedback loop between the game process and the player;” shared involvement, “all aspects of communication with and relation to other agents in the game world;” narrative involvement, “a game world’s history and background” as well as “the player’s interpretation of the game-play experience;” and spatial involvement, “locating oneself within a wider game area than is visible onscreen.”28 To Calleja, not all of these frames need to be activated to achieve incorporation with a game. Instead, engagement through the frames Calleja describes occurs on an individual basis, a specific and mutable relationship between the individual playing and the game being played.

No doubt my experience playing Stranglehold diverges from the play experiences of those who have never watched a John Woo film or are uninterested in Hong Kong cinema, and differs also from those with other interests in video games. Personally, I love video game narratives that I find engaging and intelligent, like those touching narratives of redemption constructed in Rockstar games and the minimalist dystopian stories of the Half-Life (Valve, 1998 and 2004) franchise. Halo 3 (Bungie, 2007), Assassin’s Creed II, and Stranglehold lose my interest quickly; with Halo 3 and Assassin’s Creed II, not playing the earlier installments in the franchise rapidly renders the new narratives incomprehensible, while the uninspired story of Stranglehold made me long for Woo’s cool, calculated, and downright sexy moments of narrative exposition, nonexistent in the film’s video game sequel. My experience playing Stranglehold was decidedly influenced by my personal history with Woo’s Hard Boiled, particularly my fascination with the choreographed action that had so astonished me years ago. The narrative frame of Calleja’s model remained dormant, while the tactical, performative, affective, and spatial frames were heightened as I beheld a spectacle that I had worked to create which, for me, effectively echoed the potency of a Woo action sequence.

Two considerations emerge from this reminiscence upon my experience of playing Stranglehold after spending my formative years of cinema spectatorship watching Hard Boiled in astonishment. First, game play is a highly individual experience. Polemically declaring the true pleasures of video games to be found only in game narratives, or only in effectively operating within a complex rule system, assumes that everyone should play video games for the same reasons. Yet the reasons players play games differ drastically, much as do games themselves, and game scholarship should reflect this diversity in both its methodologies and its subjects. Second, video games should never be considered to exist in a vacuum outside the influence of both other games and other media forms. This is not to say that studying singular games is unproductive, but is instead a suggestion that we remain aware that, as games such as Stranglehold overtly declare their affiliations with other media and other mediums, we should encourage critical analysis that is conscious of this media hybridity, and not dismiss such criticism as having little to offer. Game theorists should be aware that our experience of contemporary media does not respect the distinct boundaries that separate games from films. Encouraging multi-media, multi-methodological approaches to games, and to films, will work to expose these connections. Much as bullet time has blasted through the media boundaries distinguishing games from films, so too should contemporary game and film scholarship.

NOTES

- The classification of video games is a subject of scholarly inquiry and a variety of typologies have been proposed. As with the application of film theory and film analysis to video games, the usefulness of importing genres from cinema is debatable, as such categorizations frequently emphasize narrative and thematic elements while ignoring the forms of interactivity and the visual perspectives present in individual titles. Mark J.P. Wolf argues, “player participation is … the central determinant in describing and classifying video games, moreso even than iconography,” and therefore video game genres should be differentiated through the forms of interactivity unique to each game. See Mark J.P. Wolf, “Genre and the Video Game,” The Handbook of Computer Game Studies, eds. Joost Raessens and Jeffrey Goldstein. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005. 193.The designation “third-person shooter” denotes a game in which the visual perspective of the player is located at a remove from the player-character they control, usually positioned slightly above and behind. Shooting projectiles at advancing non-player characters is the “core mechanic” of the game, a repetitive action that allows for both spatial advancement and narrative progression. Numerous games, Stranglehold and Max Payne (Remedy Entertainment and Rockstar Games, 2001) included, are solely third-person shooters, as the only form of interaction possible is to run through bounded spaces dispatching enemies with gunfire. Other games, such as Grand Theft Auto IV (Rockstar North, 2008) and Red Dead Redemption (Rockstar San Diego and Rockstar North, 2010), are partially third-person shooters, as certain discrete moments of play require the form of interaction described above, while other moments alter functionality drastically, emphasizing driving, racing, collecting, and many other varied forms of play. For these and other genre definitions, see Wolf, “Genre and the Video Game,” as well as Espen Aarseth et al., “A Multi-Dimensional Typology of Games,” paper presented as part of the Level Up Conference proceedings (Utrecht, Germany: Utrecht University and Digital Games Research Association, 2003), available on-line at http://www.digra.org/dl/search_results?general_search_index=aarseth, last accessed 15 May 2011.

- Film scholar David Bordwell discusses Hard Boiled as epitomizing a “surge in production values” in late-1980s and early-1990s Hong Kong cinema resulting in “glossy spectacles” (74) that attained international recognition and allowed Hong Kong directors, John Woo first and foremost, the opportunity to helm Hollywood film productions. Hard Boiled “was greeted by disappointing box office and critical indifference [in Hong Kong] but proved quite successful overseas in the wake of The Killer [Woo, 1989].” Bordwell writes, “America’s studios have long attracted a flow of foreign talent, and once Hollywood decision-makers got a glimpse of Hong Kong cinema, it was likely that some directors would be emigrating—especially when producers realized the growing significance of the Asian market.” (85) Bordwell specifically discusses Hard Boiled producer Terence Chang, a graduate of NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, as a savvy international businessman who built up Woo’s reputation in the United States so that Woo, along with Hard Boiled star Chow Yun-fat, could enter into the Hollywood film industry. (86, 99) See David Bordwell, Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 74, 99, 85-86 respectively.During his tenure in Hollywood, John Woo directed Hard-Target (1994), starring Jean-Claude Van Damme, Broken Arrow (1996), starring John Travolta and Christian Slater, the financial and critical success Face/Off (1997), starring Travolta and Nicolas Cage, Mission: Impossible II (2000), starring Tom Cruise, and Paycheck (2003), starring Ben Affleck, Aaron Eckhart, and Uma Thurman. His most recent film is Red Cliff (2008), starring Tony Leung and Takeshi Kaneshiro, signaling the director’s return to Chinese-based film production, albeit on an epic scale clearly different from his Hong Kong films of the late 1980s and early 1990s, in terms of both production and narrative. After Hard Boiled’s release, Chow Yun-fat appeared opposite Mira Sorvino in The Replacement Killers (Antoine Fuqua, 1998), opposite Mark Wahlberg in The Corruptor (James Foley, 1999), opposite Jodie Foster in Anna and the King (Andy Tennant, 1999), in the internationally-composed and Academy Award-nominated Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Ang Lee, 2000), opposite Seann William Scott and Jamie King in Bulletproof Monk (Paul Hunter, 2003), and opposite Johnny Depp in Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (Gore Verbinski, 2007), among others, while also starring in Hong Kong-based productions without the international scope of the aforementioned titles.

- Hard Boiled and Stranglehold are here discussed as intellectual properties that cross the boundaries between cinema and video games, yet they also epitomize an international boundary crossing as well.

- Here, I borrow the term “incorporation” from Gordon Calleja, who perceptively discusses the multiple ways in which video games may invite players into the game play experience, encouraging them to forget the boundaries, such as the controller and screen, that clearly demarcate the difference between the real and the virtual. Incorporation differs importantly from immersion, which is the feeling of finding oneself completely overwhelmed within a virtual world, such as on a holodeck. See Gordon Calleja, “Digital Game Involvement: A Conceptual Model,” Games and Culture 2, no. 3 (2007) and Janet H. Murray, Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace (New York: The Free Press, 1997).

- See Mark J.P. Wolf, “Space in the Video Game,” The Medium of the Video Game, ed. Mark JP Wolf.Austin, TX: The University of Texas Press, 2002; Bob Rehak, “Playing at Being: Psychoanalysis and the Avatar,” The Video Game Theory Reader, eds. Mark JP Wolf and Bernard Perron. New York: Routledge, 2003; and Geoff King, “Die Hard/Try Harder: Narrative, Spectacle and Beyond, from Hollywood to Videogame,” ScreenPlay: Cinema/Videogames/Interfaces, eds. Geoff King and Tanya Krzywinska. London: Wallflower Press, 2002.Geoff King and Tanya Krzywinska’s anthology ScreenPlay: Cinema/Videogames/Interfaces explores the permeable boundary between cinema and video games, ranging from discussions of representation (for example, how science fiction films depict the future of video games) to analyses of cut scenes (the normatively non-interactive moments within video games that disclose narrative through cinematic editing). Itself an experiment, ScreenPlay celebrates a multi-modal approach to the issue of cinema and video game hybridity, carefully avoiding polemics and displaying a variety of scholarship that analyzes how diverse media interface with one another.

- To call films non-interactive is a simplification. Any film viewed on DVD becomes an interactive media text, where viewers have the ability to alter playback drastically. Some films take the DVD’s interactive potential further, allowing for the revelation of narrative information not included in the theatrical release. In limited cases, such as Final Destination 3 (James Wong, 2006), the viewer can choose the fate of certain characters, in this instance causing them to die in gruesome ways that differ from the deaths present in the original film. Easter eggs and special features allow for interactions with the film text’s unfolding and investigations into production histories. However, film is here considered non-interactive in that, in classically understood film viewing, spectators have no ability to alter either the narrative or their perspective upon onscreen events through personal activity. Domestic digital film viewing differs importantly from theatrical film viewing, and in certain cases introduces game modalities into the experience of cinema.

- It is important to note that games conclude in various ways. Early arcade games such as Donkey Kong (Nintendo, 1981), Pac-Man (Namco, 1980) and Space Invaders (Taito, 1978) conclude when the player loses all the lives allotted to them. As no win condition exists, play continues infinitely, increasing in difficulty, until the loss of all lives occurs and the player is provided an infamous “Game Over” screen, which are now generally absent from contemporary triple-A console titles. As video games moved into the home during the 1970s and 1980s, their forms changed as well, as the continual demand for coin drop, which brief moments of heightened interactivity in the arcade guaranteed, gave way to an abundance of time within a domestic space where the financial investment was complete before the game was even played. Games like Super Mario Bros. (Nintendo, 1985) conclude not only when players lose a certain number of lives but also when they complete a series of levels and effect an outcome that brings closure to the game’s minimalist narrative, such as finally rescuing Princess Toadstool from Bowser’s castle. Today, players themselves frequently determine video game conclusions. To some, a narrative conclusion may signal the end of sandbox games such as Grand Theft Auto IV and Red Dead Redemption, even when there are numerous activities left uncompleted. Other players only consider these games complete after one hundred percent of all possible activities have been exhausted. In contrast to earlier games, the player’s character can expire infinitely, without the game ever coming to an end.

- Jenkins is certainly not alone in considering the importance of spatial exploration to video games. For Jenkins’ discussion of game spatiality and narrative, see Henry Jenkins, “Game Design as Narrative Architecture,” in The Game Design Reader, eds. Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006. For a resoundingly clear discussion of spatial exploration in video games, see James Newman, Videogames (London and New York: Routledge, 2004), specifically chapter 7, “Videogames, space and cyberspace: exploration, navigation and mastery.”

- See Harrison Gish, “Playing the Second World War: Call of Duty and the Telling of History.” eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture, v. 4 n. 2 (2010) for a discussion of Call of Duty’s multiple, intertwining narratives.

- Neitzel, Britta. “Narrativity in Computer Games.” The Handbook of Computer Game Studies, eds. Joost Raessens and Jeffrey Goldstein. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005.

- For example, Super Mario Bros. (Nintendo, 1985) presents the player with a two-dimensional plane that moves from left to right, through which players must manipulate Mario, controlling the iconic player-character so that he eliminates oncoming enemies, avoids falling into bottomless pits, and reaches the end of the level within a pre-determined timeframe. In contrast, Doom (id Software, 1993) presents the player with a three-dimensional space oriented towards the player’s point-of-view, which players must navigate while destroying enemies with a variety of weapons and simultaneously avoiding oncoming fire, without a prescribed timeframe. Wholly different in terms of perspective, design, spatial and temporal limitations and game play, the experience of playing both games is highly dissimilar. To ludologists, such interactivity-based avoidance of obstacles and achievement of goals, in all its possible variety, is the heart of game play, while Super Mario Bros.’s narrative of rescuing Princess Toadstool from the villainous Bowser and Doom’s narrative of a space marine combating demons from Hell on the moons of Mars are entirely secondary. For ludological discussions of narrative’s role in video games, see Jesper Juul, “Games Telling Stories? A Brief Note on Games and Narratives,” Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Games Research 1.1 (July 2001), available at http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/juul-gts/, last accessed 15 May 2011, and Espen Aarseth, “Aporia and Epiphany in Doom and The Speaking Clock: The Temporality of Ergodic Art,” in Cyberspace Textuality: Computer Technology and Literary Theory, ed. Marie-Laure Ryan (Indiana University Press, 1999). For a rebuttal of Juul and Aarseth, see Marie-Laure Ryan, Avatars of Story.Minneapolis: Regents of the University of Minnesota, 2006, specifically Chapter Eight, “Computer Games as Narrative.”

- Juul, Jesper. “Games Telling Stories? A Brief Note on Games and Narratives,” Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Games Research 1.1 (July 2001), available at http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/juul-gts/, last accessed 15 May 2011

- Aarseth, Espen. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature.Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.106.

- Caillois, Roger. Man, Play and Games.University of Illinois Press, 2001. 27-29. Originally published in the French as Les jeux et les homes.Paris: Librairie Gallimard, 1958.

- King, Geoff and Tanya Krzywinska. “Cinema/Videogames/Interfaces” ScreenPlay: Cinema/Videogames/Interfaces, eds. Geoff King and Tanya Krzywinska. London: Wallflower Press, 2002. 1.

- Henry Jenkins discusses the enlargement of virtual worlds through multimedia properties as “world-making,” in which expansive worlds are designed that can be explored through cinema, video games, comic books, literature and other media forms. To Jenkins, the “world-making” phenomenon, through its careful appeal to and engagement of fan interest, differs from ancillary marketing, in which a major release in one medium is industrially exploited into other media so that financial revenue may reach a maximum. See Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York and London: New York University Press, 2006. Especially chapter 3, “Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling.”

- For more on the narrative and ludic elements of cut scenes, see Rune Klevjer, “In Defense of Cutscenes,” available on-line at http://www.digra.org/dl/db/05164.50328, last accessed 2 June 2011.

- For a book-length study of the co-functioning of the film and video game industries, see Robert Alan Brookey, Hollywood Gamers: Digital Convergence in the Film and Video Game Industries.Indiana University Press, 2010. For an anthology interrogating multiple connections between films and video games, see Geoff King and Tanya Krzywinska, ScreenPlay: Cinema/Videogames/Interfaces.Wallflower Press, 2002. For a historical discussion of how Hollywood has mobilized video games industrially and narratively, see Harrison Gish, “Representation of Video Games in Hollywood Cinema,” in The Video Game Encyclopedia, ed. Mark Wolf. Greenwood Press, 2012, forthcoming.

- Teo, Stephen. Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions. London: BFI Publishing, 1997.178, 180.

- Bordwell. 100, 226-229.

- This and all quotes within the paragraph are from Bordwell, 220-228.

- King. 62.

- King. 57.

- This same functional effect is present in Red Dead Redemption’s Dead Eye targeting system, sans the player-character leaping through the air. Player-activated slow motion is, however, used to a different effect in Red Dead Redemption, as players are in far more control of where their player-character will arrive after the Dead Eye meter runs out, and because players can place targets which the player-character will fire upon after the Dead Eye meter depletes.

- Calleja. 254.

- In fact, no game has really ever allowed me to achieve this mythic state, no matter how engaging it may be. Having to manipulate a controller to produce a desired in-game result, I am always aware when playing that I am controlling a virtual construction through a physical remote.

- Ibid. 254.

- Ibid. 239-252.

Media Boundaries and Bullet Time: A Hard Boiled Fan Plays Stranglehold by Harrison Gish is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.