Impact on Soft Power of Cultural Mobility: Japan to East Asia

By Seiko Yasumoto

Introduction

Japan, perhaps better known for its industrial and economic power, has also made significant contributions in the domain of popular culture. In recent times, there has been a burgeoning in the form of cultural exchanges between Japan and countries not only in the Asian region, but also globally in the form of adaptations of Japanese popular media for overseas consumption. Japanese popular cultural products have been transferred to different countries using different formats including television drama, film, anime, manga, computer games and music.

My essay examines the significance of the cross-cultural adaptations of popular Japanese media as a vehicle enabling the promotion of greater cultural tolerance, empathy and understanding between nations. In consideration of the ambivalent attitudes toward Japanese products in light of the history of the political hostility between Japan and neighbouring nations in the Asia-Pacific region, the significance of implications for cultural empathy and acceptance cannot be overstated. This inherent “power” in Japanese media adaptations to promote cultural understanding has attracted the attention of the Japanese government and international academic scholars, and has been termed “soft power.” My paper will examine the significance of soft power in the context of its functions and uses in Japanese government policy and in its global consumption as popular entertainment. I will begin with a discussion of the background of the concept of soft power, followed by the identification of the recent burgeoning of Japanese cultural re-makes and adaptations of Japanese media texts. I discuss adaptation as a form of soft power by examining Hana Yori Dango, a paradigmatic example of media cultural adaptation and exchange, through the use of foregrounding analysis to 1) identify distinctive features ubiquitous across adaptations, and 2) identify culturally specific modifications to the adaptations. I conclude by submitting that the cultural exchange that occurs through Japanese media adaptation and consumption through a fantasy world of mediascapes enables the projection of a new reality where cultural hybridization facilitates the mitigation of cultural prejudice in society.

Soft Power

The term soft power was first used by Joseph S. Nye Jr., Dean of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, who was an Assistant Secretary of Defence in the Clinton administration. Nye refers to “hard power” for military and economic power, and “soft power” for cultural exchanges with other countries. He also describes soft power as “the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments. It arises from the attractiveness of a country’s culture, political ideas, and policies.”1 My interpretation of soft power, in the substance of this essay, is at the micro level and focuses on the plethora of initiatives – be they commercial, artistic, regulatory or political – which combine to produce emerging macro soft power, in many cases knowingly and planned, but in many other cases unanticipated yet still contributing to soft power. Research by Ishii Kenichi, Iwabuchi Koichi and Hamano Yusuki, among others, have elucidated this trans-national soft power and its economic and cultural impacts.2 When Nye and Japanese officials speak of soft power they are talking about the ability of the attractiveness of Japanese values to get other countries to side with Japanese efforts in diplomatic and international relations. Until relatively recently, there has not been at the governmental level an active external promotion of the values in Japanese texts. There is, however, growing recognition, now evidenced in recent Japanese government initiatives on behalf of the national interest, of a need to become active in the dissemination of Japanese values and in recognising, where possible, their economic value. The inherent popularity of Japanese media products, pan-Asia and globally, is evidenced in the contribution to soft power of the numerous remakes and adaptations of Japanese media texts outside of Japan.

Japanese Popular Culture Texts

This essay focuses on what is arguably one of the strongest examples of the emergence of soft power which has led to Japanese government initiatives: the remake and adaptation of Japanese popular culture texts from their original manga (comic) form to their “osmosis” into other textual forms, especially in the East Asian region. The manga series Hana Yori Dango (Boys Over Flowers, 1992-2004) by Kamio Yoko is examined in terms of its adaptation from its original form into other media formats.

Originally, the first volume was released in manga format in 1992, and published in thirty-seven volumes over twelve years by Margaret Comics.3 It was re-made not only into several other media formats in Japan, but also adapted for audiences overseas, namely in Asia, as an animated television series broadcast by Asahi Television in 1996. It was then re-made as an anime film in 1997, by Toei Animation. Due to its popularity, it was re-made, yet again, into another television drama in Japan and broadcast by Tokyo Broadcasting Station in 2005.

A second series, Hana Yori Dango II, was re-made in 2007, and broadcast by TBS. In 2008, it was re-made as the film Hana Yori Dango: Final by Toei Studios. The original Hana Yori Dango, in the initial move from local to regional, was re-made into a Taiwanese television drama called Meteor Garden, using a Taiwanese cast for a Taiwanese audience and broadcast by the Chinese Television System in 2001. The Taiwanese version was broadcast in Japan in 2006.

Hana Yori Dango (Meteor Garden), Taiwanese Production

A Korean version of Hana Yori Dango was re-made using a Korean cast and broadcast by the Korean Broadcasting System in 2009. A Chinese version of the series was re-made and broadcast by Funan TV in 2009. Such re-making of popular culture texts into sequels and prequels across Asia reflects a creative, dynamic, and powerful force of the soft power phenomenon. With Hana Yori Dango and other iconic texts, what becomes apparent is the demonstrated capacity of these texts to cross-geographical boundaries, as well as to contribute, probably inadvertently, to the value of soft power from both the socio-cultural and economic aspects of the distribution chain. The granting of iconic status to a text is accorded, in the context of this essay, when that text has strong consumer appeal in its host country; and as a corollary, that its fundamental story content can cross international borders, be accepted, and have strong consumer appeal in the receptor countries. Hollywood has, and continues to have, many texts falling within this definition. The influence of this cycle of remaking and recycling can most clearly be seen in the soft power discussions that come to light when viewing the background and production history of Hana Yori Dango.

The Background: Towards Emerging Soft Power

Cultural trends of Japanese influence beyond Japan have manifested in three main stages of “Japonism.”4 The first stage was the influence of Japanese art on the European artists of the 1860s. The second stage was manifested in the Western interest in Japanese cultural icons during the twentieth century. For example, such interest focused on the Japanese tea ceremony, Japanese flower arrangement, and Japanese gardens. The third stage saw media being transferred regionally and globally due to a burgeoning popularity of Japanese manga, anime, and its presentation in other formats, including film and television. In stage three, many examples of media texts were remade and reformatted.

Media can only become regional and global in a broadcasting environment that enables the transmitted content to move legitimately beyond national borders. Regional broadcasting, which was restricted in the 1980’s in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, now allows for the legitimate transfer of texts across national borders. The bans preventing the consumption of Japanese cultural products in such countries as Korea and in Taiwan have been softened in a process of gradually changing legislation. The Japanese government, as with other regional governments, has progressively made explicit its perspective on media transfers. The improvement in relations between Japan and Korea was facilitated under the presidency of Kim Dae-jung (1998-2003). He instigated four steps to open the Korean door for Japan, allowing the entry of Japanese popular culture into Korea in 1998, 1999, 2000, and 2003/4.5 The first step resulted in the adverse reaction of Korea’s mass media industries, intellectuals, and academics that were hesitant to accept this new open door policy. Kim Dae-jung, who was progressive in terms of opening the door between Korea and Japan and increasingly enabling a cultural flow, saw this as the way to improve the understanding of Koreans of things Japanese, and conversely, for the understanding of the Japanese of things Korean. In Taiwan, martial law was not lifted until 1987, and the new cable television law, legislated in 1993, enabled Japanese programming on Taiwanese broadcast channels. By 1997, there were five Japanese stations available on Taiwanese broadcast television.6

There has been scholarly research in the field of remade and adapted texts conducted in the West, but Japanese scholarship in this area has been comparatively much smaller than that conducted by European and North American scholars; and there are few authentic Japanese sources relating specifically to television drama.7 Japan has been a significant contributor of primary media texts that have been a source for remaking, not only within Japan but also overseas. These texts that have not only been transformed and made successful in Japan, but have also migrated outside of Japan and been successful in pan–Asian markets and globally.8 Some of the leading examples of primary texts that have crossed geographical and cultural divides are: The Ring, Iron Chef, and The Lion King. The remaking licences for Japanese films such as Gojira (Godzilla), Akira, and Dragon Ball were granted to Hollywood.9 America purchased the remake license of The Ring for US$1,000,000.10 Iron Chef, a variety television program, which first aired in Japan from 1993 to 1999, was exported to the United States as Iron Chef America, and has continued its broadcast since 2005. Many adaptations of Japanese drama originated from manga created earlier in the twentieth century. The Lion King originated from Tezuka Osamu’s 1955 work Janguru Taitei (Jungle Emperor) and was remade into an anime film in 1977, while both the animated TV series and new Hollywood CGI film Astro Boy had their origins in Tetsuwan Atomu (1956). Other manga which has reappeared as adaptations include the first “shojo manga” (girls’ comic) Ribon no Kishi (Princess Knight) in 1958, and the “shonen manga” (boy’s comic) Wan Piisu (One Piece) in 2009. Hana Yori Dango, one of the most iconic Japanese TV dramas, also originated from manga.

Hana Yori Dango (Boys Over Flowers), Korean Production

Media popular culture has played a significant role in Japan and across Asia in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and has contributed to globalization as well as regional localization. An increasing number of re-made products have been pan-Asianally transferred. Five hundred and fifty five Japanese TV dramas were broadcast in Japan in the 1990’s, and many have been broadcast overseas.11 Japanese manga have been re-created into TV dramas; TV dramas have been re-made into films; films have been novelized into books; and books have been remade into other media forms driving regional soft power. The aggregation of media outputs has in turn created “media capitals.” For example, Tokyo in Asia, along with other Asian media cities, contributes to their respective national economies.12 For example, manga is a distinctive Japanese textual form and its production is progressively centered in Tokyo. The city acts as a magnet for retaining an existing creative pool, as well as drawing in prospective stakeholders; thus creating a critical mass of talent and production resources. The commercial outcomes initiated within Japan then become regionalized or internationalized, and add to Japanese soft power. Hana Yori Dango being a prime example of this process.

Hana Yori Dango, Japanese Television Production

The Japanese parliament strategically, if only recently, recognises the importance of cultural transfers. To quote from the policy speech made by former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to the 166th Session of the Diet on January 26, 2007:

As part of [the Asia Gateway initiative], we will also formulate the Japanese Cultural Industry Strategy, which will enhance the competitiveness of areas that represent the good traits and uniqueness of Japan, such as animated film, music and Japanese food, and present them to the world. This claim to competiveness is illustrated by the fact that sixty percent of the global production of anime and manga is Japanese.13

The appreciation of the value of cultural transfers beyond mere economics is now acknowledged, certainly by international students from Korea, Taiwan, and Japan studying at the University of Sydney, and amplified through audience analysis findings discussed later in this essay. These cultural transfers are contributing to an emerging integration of cultural elements in the region, in effect, cultural hybridization. Joseph Straubhaar defines hybridization as when “new elements from outside a culture, whether from gradual contact or major threshold change, tend to be adapted to local culture over time.14 Iwabuchi emphasizes the Japanese transnational cultural power of “Japanisation” as a shift in cultural orientation where interactive cultural flows and an intensity of reciprocal media industries exchange from Japan to Asia and from Asia to Japan.15

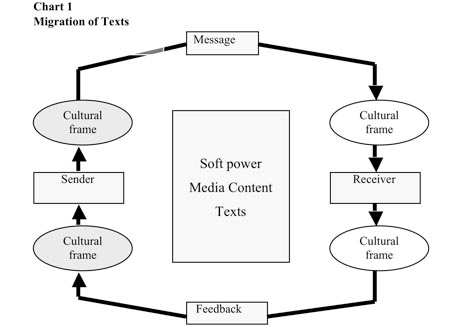

These elements and trends are very important, not only for Japan but also in the region. The reference to cultural hybridization is a recognition of both the multilateral flow and a scholarly appreciation of textual changes within the cultural flows. Texts cross cultural boundaries, and the cultural frames of the senders and receivers influence the understanding and appreciation of the content. Geographic proximity does not necessarily equate with cultural proximity, and if the texts, in whatever format, have an opportunity for commercial success, the content and form of the texts as they cross national borders has to be revised in consideration of the receiving audience’s cultural frame. If the content does not reasonably align with the expectations of the receiver, then the audience acceptance is shown to be minimal. The cultural implications are propounded by Edward T. Hall in the chart below, which illustrates the migration of texts’ “cultural ring road” and the interrelated transfer of content.16

Adapted from Walker (2007) and Yasumoto (2010)

Media texts can also have a significant impact on culture. The popularity of Hana Yori Dango in the 1990’s led to identifiable manifestations of fandom. In fashion, there was a proliferation of the “Chapatsu” (dyed blonde hair) modeled after the hairstyles of characters in the series. An increased undertaking of overseas studies in the United States and Europe was seen to confer a sense of status, and “J-Pop” singers such as the pop group Arashi rose to cult status after significant exposure through the series. Arashi also gained popularity in East Asia. “Purikura” (photo stickers), “kogyaru” (girls emulating stars), “atsuzoko boom” (platform shoes), and “cosplay Maid” (French maid costumes) all became elements of the fan culture.

Triangulation Analysis of the Manga of Hana Yori Dango

The Hana Yori Dango manga, a popular culture text, is a romantic comedy in the genre of “shojo” (girls) manga by Kamio Yoko, and its appealing content was the basis for remakes in other media formats. In my opinion, it is the core story that creates not only the local but also the regional or international appeal. This regional or international appeal then translates into Japanese soft power and elevates the status of Japan in the receptor regions. Foregrounding, the essence of the story, is the driver for this development. The following is my synopsis of the Hana Yori Dango manga as a precursor to analysis of the text.

Hana Yori Dango, Original Japanese Manga Volume 1, Cover

The protagonist is Makino Tsukushi, a girl from a plain and poor family who is forced by her parents to attend the well-known and eminent private high school, Eitoku Gakuen. The school children generally make an ostentatious display of wealth. For example, there are kindergarten children who commute to school via chauffer-driven luxury cars such as Mercedes Benzes, BMWs, Audis, and Rolls Royces. Tsukushi is an active and fair-minded girl. The high school is dominated by a gang of handsome but arrogant students called F4 (flowers four) named Domyoji Tsukasa, Hanazawa Rui, Nishikado Sojiro and Mimasaka Akira. The four boys are heirs of the most influential families in Tokyo. In the beginning, Domyoji, the school gang leader, whose billionaire mother shares and runs an international business venture in New York, hates Tsukushi for no reason and takes every opportunity to bully and play tricks on her. Over the course of many incidents, Tsukushi comes to understand the reason behind Domyoji’s arrogance and violence. Eventually, Tsukushi gains Domyoji’s respect, and he subsequently falls in love with her. Domyoji and Tsukushi eventually begin a romantic relationship together.

Let me now turn to the 1) foregrounding, 2) text, and 3) audience analyses of Hana Yori Dango. This triangulated analysis was adopted to determine the underlying dynamics of the “message”: the textual content and the audience reception of the television drama productions. This study includes an analysis of thirty-seven volumes of the original Japanese manga of Hana Yori Dango, eighteen episodes of the Japanese TV drama series adaptation, twenty-five episodes of the Korean drama series remake, and twenty-four episodes of the Taiwanese drama series remake. If the outcome of the analysis demonstrates that the text chosen for analysis has indeed migrated regionally with commercial success, then some of the ingredients of soft power have been fulfilled. A multiplier effect occurs with texts in other genres such as J-horror (Japanese horror films), which are particularly popular in Hollywood remake productions.

1. Foregrounding analysis

In examining remakes of Hana Yori Dango across Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, the aim of the analysis was to confirm whether the foregrounding in the original manga text had been transferred into the television drama content. Two questions were considered in the analysis to establish if specific content characteristics could be seen to account for its popularity in Japan and subsequently pan-Asia:

a) What are the salient constituent elements characterising the original manga of Hana Yori Dango?

b) Are the original elements retained in the remade versions of the original manga?

These questions aim to identify salient features of the original and adaptations, and identify any presence of subtle, culturally specific, modifications aimed to suit the audience and make the adaptation more accessible.

In addressing the above questions, the linguistic technique of “foregrounding” has been used. Foregrounding has been described by Mark Halliday as “achieved by linguistic devices in the foreground text standing out... highlighted or prominent in the body of the text.”17 Ruqaiya Hassan states, “the concept basic to foregrounding is that of contrast,” since “foregrounding becomes noticeable because of its consistency, and foregrounding would be impossible without the existence of a consistent background.”18 Chart 2 below identifies the salient, distinctive characteristics within this analysis of Hana Yori Dango considered in the two foregrounding questions.

Foregrounding: Identification of Distinctive Thematic Elements of Various Versions Hana Yori Dango Chart

These “foregrounded”elements are identified and summarised as consisting of: friendship, courage, overcoming adversity, romance, kindness, aspiration and vitality. There are many shared elements across the various adaptations and the fact that these particular thematic elements of the storyline have been retained across the range of television drama presentations arguably reflects cultural proximity in that they have not been subject to cultural modification in adapted versions, as have certain other features discussed below. Chart 3 on the other hand reflects the culturally specific modifications that have been made to Japanese idiomatic expressions.

2. Text analysis

The text analysis isolates six headings: cultural expressions, societal positioning and lifestyle, locations, youth culture, foreign language inclusion, and humour. Chart 3 is a small sample taken from the heading of cultural expressions. Words have different meanings and emphases within definable cultural groupings, and when texts move into different cultures and different languages, their interpretation can be very subjective and highlight differences in perspective. Consensus of meaning even within the closest family group may not be assured. Perceived humour or pathos in one culture may have a very different interpretation in another culture. Chart 3 is a small representation of Japanese words and phrases which have cultural implications translated into English explanations. These cultural expressions have not been transferred into the Taiwanese and Korean TV drama productions. Iwabuchi refers to the lack of a “Japanese odor” where the storylines may be simple and transportable (odourless), though the cultural expressions within the Japanese manga are invariably specific to Japan.19 Further study will determine if the essence of the expressions are portable.

Text Analyses of Cultural Expressions Chart

The cultural implications of the selected phrases are documented in the second column. Eighty-one cultural elements that contain many Japanese cultural nuances and expressions were identified, amongst which sixteen representations have been selected. As can be seen, the references, idioms, and metaphors are culturally specific. This highlights one of the issues of adaptation for different cultural audiences: the remaking of original cultural texts, modified to suit the audience, necessitates that in translation and adaptation the cultural meanings may be lost or hybridised, thus taking on new forms. The Taiwanese television drama version of the Hana Yori Dango manga was renamed Meteor Garden.

This production retained the overall structure and the “skeleton” of the storyline of the original manga. Portions of the original storyline and elements were not used in the episodes. The original manga was set in a high school, whereas the Taiwanese version has older characters moved into a university setting. Interestingly, one of the defining characteristics of the Japanese production, its setting in an exaggerated upper-class fantasy environment including well-known and iconic local and international locations, was changed to a setting nearer to everyday reality. In this sense, the content of the Taiwanese television drama appears to displace the main message of the Japanese version, which is aspiration for a “better” life. The “iconic luxury” elements of the story, perhaps more than extravagant for the majority of the audience, were missing from the Taiwanese version, and the fantasy element of the original manga thus discarded. The repositioning of the drama from a fantasy to a completely different and more mundane perspective in content and location was a somewhat surprising contrast to my research preconceptions. The bullying scenes were more overt in the Taiwanese drama than those depicted in the Japanese manga, the body language and expressions of characters more severe, and there was a greater focus on the love story.

The pace of the television drama develops more quickly than would be anticipated when compared with the manga text and the Japanese television production. Japanese cultural expressions were replaced in the remake. For example, an authentic Japanese “dango” (sticky rice sweets) shop is replaced by a cake shop. The substitution of the fantasy by a local reality is an interesting cultural differentiation.

The Korean television drama version places emphasis upon the love story, relationships, fashion, and parties. Settings are extraordinarily luxurious and the music foregrounds and romanticises the scenes. In the musical score of the Japanese television drama production, only a solo violin is featured. In the Korean version, violin, guitar, piano, harp, orchestra and love songs are featured. The emphasis on bullying, as in the Taiwanese production, was more overt than the original manga and portrayed in a Korean context. Japanese cultural implications and expressions were discarded. Localisation was clearly in evidence through the production to sustain the relationship of accessibility between the audience and the text. The main “shojo” (young girl) character was portrayed as more dominantly strong-willed and assertive than her Japanese counterpart. Overall, the Japanese cultural elements were displaced by Korean elements that a Korean audience would be sympathetic towards. For example, the Japanese tea ceremony house was replaced by a Korean pottery shop. In terms of the luxury setting, the Korean production is close to the original manga, retaining and even reinforcing the fantasy content. The productions, broadly speaking, were similar and the location of the drama was changed from Japan to Korea.

It is interesting to compare the Taiwanese and Korean productions of Hana Yori Dango with attitudes and opinions expressed by a focus group of Sydney University students and contemporaries, which met in 2009, and were comprised of natives of Taiwan, Korea, and Japan. The Korean and Taiwanese focus group members wanted to know more about Japanese culture and were very interested in what was happening among Japanese youth. In an interview, which I conducted with the President of the Taiwanese Youth Society of Australia, he observed that Taiwan has adapted, and still now adapts, Japanese popular culture. The Korean group said that young Koreans, particularly in high school, copy Japanese culture, whether it is good or bad, such as the negativity of “ijime,” or bullying.

Hana Yori Dango has certainly added to the fan culture in East Asia and its acceptance, in some cases even with substantive repositioning, has illustrated elements of commonality of regional values in the regional acceptance of its content. Not only the story, but also other factors are seen to represent “Japaneseness” and are attractive to youth across Asia. If the essence of what is attractive to pan-Asian youth and beyond can be distilled, it is in the Japanese imagination, which makes the superficially impossible possible and realises dreams often buried in the human psyche, converting them to conscious realities. The international appeal of Japanese manga and its remaking perhaps confirms this opinion.

3. Audience Analysis: Japanese Reception of Hana Yori Dango

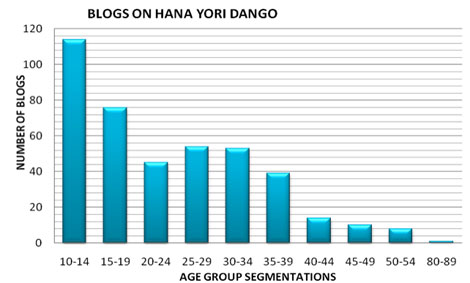

As a precursor to the formal audience analysis, various Japanese “blogs” relating to Hana Yori Dango were collated and are illustrated in Chart 4.

Chart 4: Audience analysis

Japanese Reception: TBS Blog Analysis: August 31-September 1, 2007

The data was collected by accessing the TBS Blog between August 31 and September 1, 2007. The predominant age group expressing their thoughts and views on Hana Yori Dango via the internet were those in the age range of ten to fourteen years old. The number of samples declines steadily from this age group to the oldest age group, with the contributors between the ages of twenty to twenty-four years old being slightly under represented as compared to their expected numbers. Gender was heavily weighted to females: of the 429 bloggers, only three were male. The Internet may be a challenge for some, but the blog in the eighty to eighty-nine years age group was inspirational. This substantive variation in interest and preparedness to publish views is worthy of more analysis. Superficially, one can assume that Hana Yori Dango is interesting to the female segment of ten to thirty-nine year olds.

Texts without an audience may be seen to have no attributed meaning. The content values are dependent on perception. The study has included audience analysis to determine the factors that engage (if at all) the prospective audience in the text.

Focus Group in Australia

This analysis utilised the benefits of the Australian multi-cultural university environment to interview international students from Japan, Korea, and Taiwan in a common location away from their home countries. The research method applied for Hana Yori Dango took the form of sampling with a seven-part survey form and ensuing focus group discussions. The focus group interviews were conducted in Sydney on June 9, 2009, and June 13, 2009.

In order to understand the audience reaction, audience discourse was attempted from two perspectives: both texts and cultures were compared to ascertain how the audience interpreted the essence of the original text, which elements that appealed to them, and what elements were shared or differed in terms of cultural proximity. Jason Sternberg states that, “The interview with these groups was used in order to develop ‘tertiary audience texts’ containing discourses that could be used to examine the ways in which fans communicated with others.”20 Group discussions rather than individual discussions were used following the method of Peter Lunt and Sonia Livingstone involving “collecting a group, or more often, a series of groups of people together to discuss an issue in the presence of a moderator.”21 Focus groups are effective for “speeding up sampling for one to one interview.”22 The method was used as an addendum to the questionnaire to support validity, reliability and control group interviews. The focus groups were given the questions forty-five minutes before the focus group interview and allowed to take preliminary notes. The interview respondents were then taken to recording studio 103 in the Multimedia Centre at the University of Sydney. The interview was conducted over approximately forty-five minutes and respondents discussed freely in response to questions. The focus group interview questions were subdivided into sections relating to: A) Program related questions, B) Text related questions, C) Cultural viewpoint questions, D) Viewing format, E) Government policy, and F) Representations of Japan.

This research was conducted with three groups of Japanese native speakers (3 male, 3 female), Korean native speakers (0 male, 4 female), and Taiwanese native speakers (5 male, 5 female). Their ages ranged from nineteen to twenty-four years old and the volunteer respondents were a mixture of undergraduate and post-graduate students at the University of Sydney. The Japanese group is currently taking both the undergraduate course in Japanese Media Culture and the post-graduate course in Asian Popular Culture, and the Korean group is enrolled in the undergraduate course in Japanese Media Culture. The Taiwanese group is comprised of students from the Taiwanese Student Youth Society at the University of Sydney, as well as Taiwanese students from the undergraduate course in Japanese Media Culture.

It has been suggested by research that the ideal number for focus groups is no fewer than six and no more than ten participants.23 As suggested by Jason Sternberg, in order to set up and create a friendly atmosphere, two participants from my educational network were placed in each group and asked to bring their friends or acquaintances so that the participants would know each other before the interviews, feel relaxed, and talk freely within the limited time of interviews: “The members of each group came from the same population, were well known to and interacted well with each other, and the interviews were conducted in an environment familiar to the group.”25 Some interview principles and conditions followed Sternberg’s ideas of the effective interview process, namely that participation in this group interview was voluntary and subjects were free to partially and fully withdraw from the study at any time.

As a snapshot, some comments have been extracted from the interviews, which reflect some Korean perceptions of the Japanese media in the context of cultural mobility, interrelations between Japan and Korea, and the role of technology in facilitating cultural proximity and understanding between the countries. These comments reflect awareness of the political implications of media cultural exchange through adaptation of popular texts as well as their observations of cultural distinctness. Some student comments from the nineteen to twenty-four age groups (Korean, Taiwanese and Japanese) include:

Fan A: “Japanese type of humour is kind of different from Korean.”

Fan B: “I watched a lot of Japanese dramas.”

Fan C: “[The] Japanese anime version was definitely more serious. Humour really makes it. There is a big contrast. Korean sticks to more serious, dramatic, romantic. They love to create tension between characters concerning romance.”

Fan D: “I remember reading comic books from an early age. Have an older brother. Japanese illegally translated. I think it was just the natural step. Keeping up with the globalisation. We can’t just discriminate against one particular nation because of the local history.”

Fan E: “I think Korea’s still quite closed in some sense. Because the government relied upon public opinions [sic]. Korea is swayed by that. Older generations hold power politically. If they are against it, Korea is still closed and can’t change much. Younger generations don’t care as much; carefree about it and just goes with older generation.

Fan F: “New technology provided other means.”

Fan G: “Technology in Asian countries is ahead globally speaking. Technology is something everyone needs and enjoys and that opens up new doors.”

These comments highlight some of the issues facing Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese audiences in the consumption of Japanese media products and their remade counterparts. The replies to the survey question “What aspects of Japan are conveyed through Japanese media products?” illustrate that, first, the Japanese group valued cute culture, anime, technology, pop culture and manga; second, the Taiwanese group valued pop culture, Japanese culture, cultural exchange, social issues, and Japanese film; and third, the Korean group valued pop culture, anime, manga, beauty culture and Japanese culture including the tea ceremony. The responses suggest the willingness and openness of youth across the three cultures to embrace change and move on from historical prejudices and an identification of distinctive cultural characteristics where both Taiwanese and Korean students (potentially the leaders of the future) valued Japanese culture and media products.

The previous governmental legislation in Korea prohibiting and regulating the import of Japanese media, juxtaposed with the illegal consumption of Japanese media by Korean fans, was reflective of the ambivalent attitudes toward Japanese products resulting from Japanese colonisation of Korea from 1910 to 1945. Yet in the past decades, the great popularity of Japanese media, reflected in the burgeoning pan-Asian remaking of Japanese media, has facilitated cultural mobility, which in turn has significant implications for future empathy between East Asian nations. Technological advances, for example, the production and distribution of compact discs, memory sticks, satellite broadcasting, computers, television, the internet’s ability to enable the easy transfer of texts, and an appreciation of Japanese cultural items riding over historical antipathies, are all particularly evident in the younger generations as illustrated in the student comments above. The Japanese government has recognised in the global popularity of Japanese media products such as Hana Yori Dango, among other anime and manga media products, a form or element within soft power concurrent to economic power in the transfer of these products.

Conclusions

At this time, regional soft power in the form of media transfers of popular culture is active in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, and texts move freely across national borders. Hana Yori Dango is a classic example of these transfers from its origin as a manga into anime, film, and television drama formats with regional productions localised but retaining the core values of the original text. The predominately positive reception of Japanese media transfers by the incoming and upwardly mobile younger generations can be seen as contributing to an improvement in regional political relations and thereby more cultural transfers and better mutual understanding.

Fandom has several manifestations that propagate and consolidate the enjoyment of popular culture media products. The adoring audiences create new societies in both local and regional contexts as communication and ideas flow to and fro across geographical boundaries and contribute towards a hybrid group where a variety of ideas, thoughts, and feelings meet in cohesion with many shared human qualities deriving from fundamental commonalities and new stimuli. The fantasy world of mediascapes in effect moves the audience towards a new reality where barriers progressively dissolve and hybridization facilitates the mitigation of cultural prejudice in society. Commonality can be shared and mutually enjoyed, and audiences create a new culture and world where they communicate through media products such as Hana Yori Dango and other forms of remaking towards a new cultural reception. The regional success of Hana Yori Dango and the regional and international success of other manga together with texts in other genres certainly confirm the relevance and importance of soft power enunciated by Joseph S. Nye within the qualification of this essay’s definition and in the emerging global village.

NOTES

- Nye Jr., Joseph S. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs, 2004. x.

- Iwabuchi, Koichi. “Cultural Globalization and Asian Media Connections.” Feeling Asian Modernities: Transnational Consumption of Japanese TV Dramas. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004. 1-22.

- Kamio, Yoko. Hana Yori Dango. Margaret Comics. Vols. 1-37. Tokyo: Shueisha, 1992.

- Takashina, Shuji. Japonizumu Nyumon. Kyoto: Shibunkaku, 2000. 1-10.

- Maeda, Yasutaka. “Kindaichu Daitoryo No Tainichi Taishu Bunka Kaihoseisaku No Imi Rekishiteki.” Otsuma. Joshi University Higher Education, 2007. 37.

- Iwabuchi, Koichi. Recentering Globalisation Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2002. 141.

- Curtin, Michael. “Globalisation.” Television Studies. Ed. Toby Miller. London: British Film Institute, 2005. 43-46; Moran, Albert. Copycat Television: Globalisation, Program Formats and Cultural Identity. Bedfordshire: University of Luton Press, 1998. 169-78; Mazdon, Lucy. Encore Hollywood: Remaking French Cinema. London: British Film Institute, 2000; Keane, Michael Albert Moran, and Anthony Y. H. Fung. New Television, Globalisation, and the East Asian Cultural Imagination. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2007.

- Tomoyuki, Sugiyama. Kuuru Japan: Sekai Ga Kaitagaru Nihon (Cool Japan: Japan Being Wanted by the World). Tokyo: Shodensha, 2006; Ishii, Kenichi. Higashi Ajia No Taishuu Bunka. Tokyo: Sososha, 2000; Hamano, Yasuki. Moho Sareru Nihon. Tokyo: Shoudensha, 2005; Nakamura, Ichiya and Megumi Onouchi. Nihon No Poppu Pawaa (Japan Pop- Power). Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Shinbunsha, 2006; Kelts, Roland. Japanamerica. Tokyo: Random House Kodansha, 2007.

- “Kontentsu Bijinesu No Kaigai Tenkai Nitsuite.” Ed. Trade and Industry Ministry of Economy. Tokyo: METI, 2003. 4.

- “Kontentsu Sangyo Kokusai Senryaku Kenkyuukai: Chukan Torimatome.” Ed. Ministry of Economy Commerce and Information Policy Bureau, Trade and Industry. Tokyo: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

- Ishida, Yoko. TV Dorama Ooru Fairu (TV Drama All File). Tokyo: Aspect, 1999. 1.

- Curtin, Michael. “Media Capital: Cultural Geographies of Global TV.” Television after TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition. Eds. Lynn Spiegel and Jann Olsson. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004. 270-302.

- “Kontentsu Sangyo No Kokusaitenkai to Hakyuukooka.” Ed. Ministry of Economy Commerce and Information Policy Bureau, Trade and Industry. Tokyo: METI Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, 2008. 8.

- Straubhaar, Joseph D. World Television: From Global to Local. California: SAGE Publications, 2007. 12.

- Iwabuchi, Koichi. Public seminar. The University of Sydney, 30 October 2009.

- Walker, Danielle Thomas Walker, and Joerg Schmitz. Doing Business Internationally: The Guide to Cross-Cultural Success. Ed. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003. 207

- Halliday, Mark. “Linguistic Function and Literary Style: An Inquiry into the Language of William Golding's ‘The Inheritors’.” Essays in Modern Stylistics. Ed. Donald Freeman. New York Routledge, 2001. 325-260.

- Hassan, Ruqaiya. Linguistics, Language and Verbal Art. Victoria: Deakin University, 1985. 94-5.

- Iwabuchi, Koichi, ed. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. London: Duke University Press, 2002. 1-22.

- Sternberg, Jason. “Focus Group Method.” Diss. QUT, 2010.

- Lunt, Peter and Sonia Livingstone. “Rethinking the Focus Group in Media and Communications Research.” 1996: 14. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/

409/ - Ibid. 14.

- Morgan, David and Richard Krueger. The Focus Group Kit. Vol. 1-6. California Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1998. 1-3.

- Sternberg. 164.