Globalization, Digital Films, and New Directions in Documentary

By Tom Zaniello

If we begin with definitions, we may never get to the movies.

Historically, documentaries were films with ideas, not stars. Documentaries were for exploring social and political issues destined for a campus film series or a public television station, so went the accepted wisdom, but then we happily made an exception for the more provocative post-modern film essayists like Michael Moore.

Fair enough. Perhaps. But even before digital filmmaking became routine, the varieties of documentary were impressive. Besides traditional social realist documentaries and personal post-modern explorations — the two examples just cited above — documentary had morphed into an impressive variety of forms: cinema verite (filming “real people in undirected situations”- Stephen Mamber), TV documentaries (celebrity reporter goes on location, with Frontline as the gold standard), agit-prop documentaries (targeting an injustice without regard for journalistic “balance”), structuralist documentaries (exploring imagery, landscape, and action often without a linear narrative), ethnographic fictions (using nonprofessionals to mimic an activity, sometimes scripted, as if they were doing it in “real life”), and mock documentaries (pseudo-documentaries using professional and non professional actors in scripted and semi-scripted action). For a full taxonomy and numerous examples that document globalization, see my Cinema of Globalization.

Of course, any of these documentary forms can now be made today digitally and disseminated on the Web. In fact, if their filmmakers are to reach an audience, that’s what they’ll have to do, since many of the usual venues (independent film theatres, public TV, cable TV, film societies, and campus film series) have now been extensively supplemented – in some cases replaced – by the newer modes of digital distribution.

Furthermore, as we are in the Age of Globalization, both the topics and the distribution of documentaries explicitly acknowledge that globalization and digitalization are virtual twins. One example may suffice: when the Walmart clerk scans your purchase, let’s say a set of plastic ice trays, the Chinese factory that makes them receives that digital bit of information directly in a triumph of supply chain logistics.

Today, while almost everyone believes we are in the Age of Globalization, most commentators only believe in their definition of the phenomenon. Here’s mine:

Globalization is an economic and political phenomenon involving the trans-national creation of goods and services at the lowest cost for the maximum profits of multinational corporations through the exploitation of raw materials, the employment of labor regardless of national borders, the unimpeded flow of capital, led and to a certain extent controlled by trans-national organizations like the World Bank (WB), the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Films documenting globalization are available, but what constitutes documentary is not so easily resolved. As I have tried to insinuate already, many potential viewers had already missed how varied documentary was even before digitalization. Post-digitalization in documentary has developed because the filmmakers have gone where many of their peers from the pre-digital generation could not have gone even if they wanted to.

Therefore, what follows should be more strictly labeled as “notes towards the post-digital documentary wave,” because many of the filmmakers discussed below – whether self-conscious pioneers or not – have simply re-discovered what documentary filmmakers of previous generations have instinctively practiced: what is real is what we film. And because of globalization, the topics of documentary and their countries of origin, whether filmed in real or virtual worlds, cross national borders with the speed of the Internet.

My schema is tentative and begins with only three of the new directions in documentary, and in fact I begin with probably the most familiar set, Remixes and Mashups. All three reinforce, however, what one recent guidebook asserts: when it comes to documentary, “hybrids are the rule, not the exception.”

1. Remixes/Mashups: Fanvids Grow Up

Fanvids are the avatars of hybridity. The films of Jonathan McIntosh (aka Rebellious Pixels) epitomizes the journey of fanvids into more ideological territory. His Buffy vs Edward: Twilight Remixed video - recently nominated for a 2010 Webby Award in the Best Remix/Mashup category - dramatizes Buffy’s superiority as a vampire slayer when Edward wanders out of the Twilight films and into her high school and begins to stalk her. (Hasn’t he ever seen any TV re-runs?) Twilight fans may be disappointed with this inspired and perhaps inevitable film.

McIntosh’s more politically driven remixes include Go Army: Bad Guys (log in @ You Tube) that depicts a young boy sitting confidently in an interview with his guidance counselor. As he explains that he wants to join the Army so he become one of the “bad guys”, his earnest face is intercut with footage of torture from Abu Ghraib.

So You Think You Can Be President mocks John McCain’s performance during the 2008 presidential debates by mixing footage of the excited chatter of the host and judges of So You Think You Can Dance with McCain’s (and Obama’s) speeches.

2. Digital Adverts: Visiting the Corporate Utopia

At first glance, many of the films cited below would have been dismissed as advertisements, but their scale and placement in the global market has moved them into a new category, in which the films vacillate between what exists and what might exist, all in the spirit of selling a corporate utopia.

CGI and digital filmmaking have provided the planners and financiers of global development schemes the opportunity to “show” their concepts as if they were actual places. The sheiks of Dubai are the leading auteurs in this category, although I will cite examples from Korea and Saudi Arabia as well. I have included for contrast two others, one from London whose streets are to be paved with Olympic gold and one from a district of New York City whose streets are, well, unpaved.

Dubai’s urban renewal offers the ambitious doubling of Dubai, already the largest city of the United Arab Emirates, by creating a megalopolis that will be built from scratch on the coast of the Persian Sea, or more precisely, built from sand, as the new entities are all man-made islands connected to the mainland by causeways. Falcon City combines a residential city with an ambitious resort consisting of almost full-size replicas of the major wonders of the world past and present: the Great Pyramid, the Eiffel Tower, the Great Wall of China… There seems to be no end to the list of these wonders. The name of the city derives from the Middle Eastern culture of falcon-hunting, and in fact, the structure of the man-made lagoons and peninsulae create a falcon shape visible when flying over the city. We know from published reports that this complex in Dubailand will have in effect one of the defining features of the megalopolis, a workers’ city - with migratory labor almost exclusively - but it is oddly absent from the film.

This proposed 25 billion-dollar “ubiquitous city” goes beyond the CCTV model of street-wise surveillance characteristic of the contemporary metropolis to become one of the first U-Cities with a complete net of monitoring and convenience technology. Based in part on the same RFID (radio frequency identification) tag system that made Walmart’s supply chain the envy of the globalized economy, the U City carries Wi-Fi and plastic card recognition to another level, monitoring the location of every cardholder. On the sound track the lead singer of Sigur Ros, the Icelandic post-rock band, breaks into lyrics in an imaginary language, making the new city seem even more un-real.

The Saudi Arabian megalopolis of the future will be built near Riyadh, its capital city, and is named after the Saudi ruler. Unlike Dubai’s projects, the Saudis have less to show on the ground, and the videos reflect this: they are hype rather than reality. The CGI films are light on religion but stress “Middle Easternness” - the King is the guardian of the Prophet’s mosques; we see tableaus of meetings and hotels with men only (the rare exception being burka-clad university women sitting by themselves in the education zone); and we hear of “high end” residential zones.

When London, once the imperial city par excellence, wanted to impress its old colonies and the new centers of power that it was the logical choice for the 2012 Olympics, it released this film (in different versions, depending on audience), a portrait of London as a city of runners of all sorts amid endearing British stereotypes: we see Jo Ankier, champion steeplechase runner, charging throughout London, passing street sweepers playing hockey with their brooms and bowler-hatted city workers fencing with their brollies. In short, it is city as palimpsest - London steady on, but ready to host its global neighbors.

Although Willets Point, also known as the Iron Triangle, an undeveloped thirteen-block area near Shea Stadium in Flushing, New York City, resembles the streets of John Carpenter’s dystopian prison fantasy, Escape from New York, the film was commissioned by the owners of auto repair, salvage, and related businesses who are agitating against Mayor Bloomberg’s plan to take over all their private property by eminent domain, raze the entire district, and create appropriate office and residential opportunities that will complement the new stadium of the NY Mets baseball team. The only recorded resident in this daily working community of 1,500 is not interviewed about the lack of drains and sewers. So much for the curbline. There are no curbs.

3. Faux Docs: To Be and Not To Be

Although CGI is now used everywhere, I am most interested in its use as speculative non-fiction and agit-prop documentary. For the former, a newscast in Taiwan, Tiger Woods Accident is a good example: filmmakers created two animated scenarios, the first which purports to be Tiger’s wife’s (unlikely) version in which she uses his golf club to free him through a broken window, and the second (what really happened): she scratches his face, and when he drives away, he is distracted by her pursuit with the golf club and crashes. Both animations are intercut with still photos and an excerpt from a post-accident police interview.

Alex Rivera’s Why Cybraceros?, a short film whose central idea of “remote labor systems” later became the driving idea of his first feature film, The Sleep Dealer (2008), proposes that America can have “all the labor without the worker” by using robots in the fields controlled through cyberspace by Mexican workers who never leave their native villages. Rivera shows two robots picking oranges, intercutting what appears to be a Mexican working at a terminal controlling the robots. The comic high point of the film comes in an animated sequence in which a Mexican worker jumps the fence on the U.S.-Mexico border - that’s the old way. In the new way, his arms detach and they clear the fence - that’s the “remote labor solution.”

There may be a thick line between a scripted mock-documentary with professional actors and “reality show” provocations in which the filmmakers may be the only actors around. The latter is the specialty of the Yes Men (Andy Bichlbaum and Mike Bonanno), whose independent documentary releases in theaters and on DVD, The Yes Men (2003) and The Yes Men Fix the World (2009), often cannibalize their own digital filmmaking distributed on the Web. Two of their hybrid works include Re-Code.com wherein potential Walmart consumers are tutored how to create their own bar codes to print out - and affix on goods at the stores - for their own “really low” prices:

and I’m Not Stealing ... Don’t Put Me Behind Bars, a defense of re-coding as the epitome of the American way:

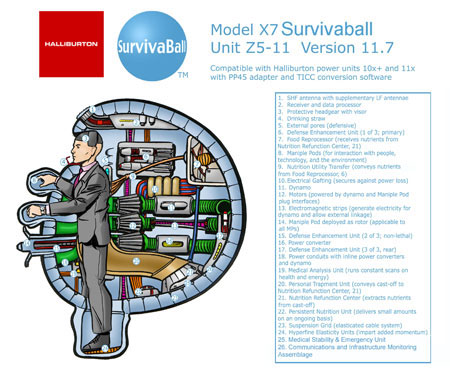

SurvivaBall, the third in this series of very brief CGI films, showcases a roomy ovoid disaster suit, supposedly provided by the Halliburton Corporation for execs to use during global disasters. All of these SurvivaBall CGIs spoof post-apocalyptic cinema: one of them features a cyber-woman dancing through deserted canyons of skyscrapers, while another offers advice for future executives: form a pile of fellow SurvivaBalls, create a floating colony, and then “dispense with unneeded units.”

The somewhat mysterious Guerrillavison, an activist and no doubt anarchist collective of filmmakers, have taken the participatory politics of other anti-globalization filmmaking groups a step further. One of the most famous of the latter groups’ work is Showdown in Seattle: Five Days that Shook the WTO, a five-part day-by-day video record of the protests against the Seattle meeting of the World Trade Organization. At least seven groups filmed the protests and pooled their footage daily, usually uploading the resultant “guerrilla” news to cable channels. Eventually they released a DVD of all the broadcasts.

Guerillavision now works, it appears, mainly digitally, with Crowd Bites Wolf, its most powerful piece of work.

On one level, the “crowd” is simply the mass of demonstrators in Prague protesting the IMF-World Bank summit, while the “wolf” is the then-World Bank president, James Wolfensohn. Lovers of cosmic justice realize that the film did not have to be re-titled in 2005 when Paul Wolfowitz followed his brother wolf as president.

What sets Crowd Bites Wolf aside from most protest documentaries is that it is simultaneously a documentary of the events and a semi-staged intervention in the activities in Prague by what seems to be a roving journalist who interviews demonstrators, attends meetings, and narrates the clashes as they unfold. He is also, it appears, a clandestine agent, receiving important memos and direction at café “drops” from mysterious strangers, information vital to the success of the demos that he dutifully passes along. A full range of digital media are also part of the film itself, as we see footage from handheld devices as well as surveillance cameras.

While Crowd Bites Wolf is probably one of the most experimental and daring of all the new directions in documentary, all the digital films I cite have enough of an edge to challenge anybody’s definition of documentary. I conclude with another challenging and evocative film, a Kanye West music video, Flashing Lights, in which the singer appears only briefly at the end trussed up in the truck of his car just before a scantily clad Amazon finishes him off with a shovel (off screen, of course):