‘Speaking as’: Selfies and Cybertyping

Jenny Gunn

Figure 1

|

In a recent article, Grant Bollmer and Katherine Guinness question the effectivity of ethnographic methods for a critical media theory of the selfie. They write, “feelings of empowerment may explain personal motivations, but they do little to elucidate the politics of whatever is performed in a specific act.”i While their recommendation moves towards a phenomenology of the selfie, I suggest an emphasis on its relationship to visual culture by drawing upon contemporary art and film engaged with processes of self-mediation in an effort to analyze the political significance of this new media form. |

| Amalia Ulman’s Instagram performance piece, Excellences and Perfections (2014), for example, exposes the circulation and investment (both monetary and affective) in white cis-gendered femininity as an aesthetic ideal within contemporary selfie culture (Figures 1 & 2). Tracking Ulman’s breast implantation through a series of selfies documenting her post-operative healing process, Excellences and Perfections examines white femininity as a patriarchal technology achieved through violent and masochistic alterations to the body.ii |

Figure 2

|

| As Alice Marwick observes of “Instafame,” i.e. the achievement of microcelebrity through Instagram, it can be difficult to assess the causal roots of an individual account’s popularity. In the case of one account that Marwick tracks, Cayla Friesz, then a high school student from Indiana, her Instafame seemed to center around nothing more than her embodiment of all-American youthful, white cis-gendered femininity (Figure 3). |

Figure 3

|

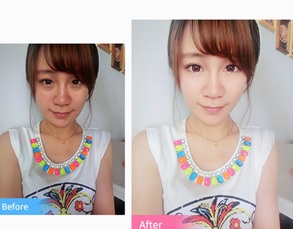

Writing for The New Yorker, Jiyang Fan similarly traces the further entrenchment of white, European femininity as a cosmetic ideal in Chinese selfie culture through the overwhelming popularity of Meitu photo-editing applications. It’s estimated that over one half of the selfies uploaded on Chinese social media applications are first filtered and cosmetically altered through photo-editing applications owned by the Meitu corporation, which additionally sells selfie-optimized smartphones. As Fan explains, “In nine years, the company—whose motto is “To make the world a more beautiful place”—has literally transformed the face of China.iv The company has done so through the perpetuation of what is known as wang hong lian, or “internet celebrity face.” As the blog “Digital Media Culture” argues, the image-based web 2.0 era has found internet celebrity evolve from an association with expert content producers in the blogging era to an association with celebrity earned solely through appearance.v With the aid of Meitu’s photo editing applications, more and more Chinese social media users--especially young women—now alter their selfies to appear more Westernized (Figure 4). These digital modifications include the single eyelid fold common in China altered to a more Westernized double fold, lightened skin, and widened eyes. These racial dynamics are further underscored by the popular “mixed blood” filter that adds a more Eurasian appearance to users.

| Meitu thus clearly illustrates the perpetuation and exacerbation of whiteness as an ideal within selfie culture. In her interviews with China’s Instafamous or “wang hong,” Fan alludes to the harm that investment in this ideal can generate, as well as to the various types of physical, emotional, and psychological damage that can result from narcissistic self-objectification more broadly. Such damage is, indeed, not small as people continue to undergo excessive plastic surgery in order to embody their filtered appearance on social media. This problem appears rampant in the United States, too, with the increasing popularity of photo-editing applications and enhancements such as those popularized by Meitu. vi |

Figure 4

|

The emergence of the selfie format is frequently analyzed in relation to the gendered construction of the gaze: does the selfie disrupt the hegemony of the male gaze or merely illustrate its further entrenchment and internalization?vii Reaching a definitive answer concerning the ontological form of the selfie seems unlikely; however, evaluations of its gender politics appear to be most productive when responding to specific selfie practices. Further, it is certain that the initial framing of the selfie’s significance in relation to the male gaze obscures attention to the function of race in the visual culture of selfies. The re-emergence of gender as an analytical category vis-à-vis the male gaze might, indeed, reproduce the earlier mistakes of second-wave feminism by inadequately attending to other intersecting identities.viii As Kimberlé Crenshaw has proven, gendered oppression does not operate apart from class and race.ix Exceeding questions of the gaze, the selfie has also been analyzed in relation to subjective narcissism.x In these conversations as well, there has been little discussion of the inherent function of race and gender in the narcissistic process of identity formation.

While Frantz Fanon famously articulates the exclusion of blackness from the reciprocity of narcissistic identification, Judith Butler argues that post-Oedipal adherence to a gender norm also functions in relation to the development of the ego in the mirror stage.xi Drawing from Freud’s association of pain and hypochondria as well as homosexuality with narcissism, Butler states that, “ . . . gender-instituting prohibitions work through suffusing the body with a pain that culminates in the projection of a surface, that is, a sexed morphology which is at once a compensatory fantasy and a fetishistic mask.”xii The post-Oedipal identification with a gender norm thus furthers the coordinating and repressive function of the ego.xiii And yet, as Butler allows in her analysis of gender as performance, the resulting identity nevertheless remains a “compelling illusion, an object of belief.xiv” Butler’s assessment of the investment placed in one’s gendered ego thus soundly resonates with Lauren Berlant’s concept of cruel optimism, which the latter defines as “a relation of attachment to compromised conditions of possibility.”xv The ego, in other words, may be the first and most formative object in this chain of cruelly optimistic attachments. Like Butler, Berlant emphasizes that cruel optimism often betrays an attachment both to the formal and the normative. She opposes this through the concept of “the impasse,” where an encounter might occur that could lead to both “the dissolution of the form of being that existed before the event” and to a “radically resensualized subject.”xvi The impasse thus opens a potential and opposing force to the attachment of cruel optimism and its complicity with “the productive pace of capitalist normativity.”xvii If as Berlant insists, however, a critique of political economy inherently accompanies analyses of cruel optimism, then we must be attentive to capitalism’s exploitation of our ego-driven attachments in contemporary selfie culture and the manner in which our narcissistic acts participate in the re-circulation of racial and gendered norms.

Writing in The Interface Effect, Alexander Galloway is attentive to the double-bind of participation in post-web 2.0 digital media. He asserts that given the hegemony of likeness and representation within social media sites, one is always interpellated through the matrices of race and gender. Galloway defines this problematic as “cybertyping”:

There is a new kind of speech online, the speech of the body, the codified value it produces when it is captured, massified, and scanned by systems of monetization. The difficulty is not simply that bodies must speak. The difficulty is that they must always ‘speak as.’xviiiIn such an atmosphere, one’s individuality is less significant than one’s value as an embodiment of a social type. So what form of action can be pursued in in response to the cruelty of always already ‘speaking as’ an embodied social identity?

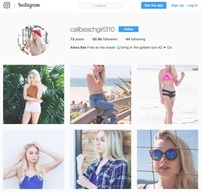

| Galloway’s pessimistic solution is to decline participation altogether, but this advice seems insufficient seeing as the fulfillment of raced and gendered ideals need not even rely on embodied acts but is increasingly achievable through simulation or what Galloway might define as a “purely idealized racial coding.”xix This new reality was recently exhibited through marketing firm, Mediakix, and its experimental monetization of a simulated Instagram personality, Alexa Rae as calibeachgirl1310 (Figure 5). |

Figure 5

|

| As these developments indicate, digital simulation alone can allow for the maintenance and enforcement of racial and gendered hierarchies. As such, how might we counteract this force by participating otherwise? While critical media theory should continue to consider the ideological function of new media forms, we must also be vigilant about the micropolitics of individual social media practices. Does the selfie necessarily remain attached to compromised conditions of possibility that reinforce gendered and racialized ideals, or can new practices help open an impasse and assert radically re-sensualized subjectivities? |

Figure 6

|

About the Author

Jenny Gunn is a PhD Candidate in Moving Image Studies at Georgia State University. Her research interests focus on critical media theory, feminist media studies, and continental philosophy. Her dissertation, Narcisscinema: Selfie Culture & the Moving Image, analyzes the affects and aesthetics of the selfie and other self-reflective new media forms and their impact on contemporary film & visual culture. Jenny is on the Editorial and Social Media Staff for liquid blackness, a research project on blackness and aesthetics. Her writing has been published in Film Philosophy and Cinephile journal. She is also the recipient of the 2018 Provost’s Dissertation Fellowship at Georgia State.

Works Cited

- Grant Bollmer and Katherine Guinness, “Phenomenology for the Selfie,” Cultural Politics, Vol. 13, No. 2 (July 2017): 160.

- Teresa de Lauretis, Technologies of Gender: Essays on Theory, Film, and Fiction (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987).

- Alice E. Marwick, “Instafame: Luxury Selfies and the Attention Economy,” Public Culture, Vol. 27, No. 1 (2015): 149.

- Jiayang Fan, “China’s Selfie Obsession,” The New Yorker, December 18, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/12/18/chinas-selfie-obsession. See also: Yuejia Wang, “‘We Are Famous on the Internet’: A Study of the Chines Phenomenon of Wanghong"” (University of Bergen, 2017), http://bora.uib.no/bitstream/handle/1956/17096/We-are-Famous-on-the-Internet-A-Study-of-the-Chinese-Phenomenon-of-Wanghong.pdf?sequence=1.

- 网红Wang Hong: A Report on China’s Social Media Microcelebrities,” Digital Media and Culture (blog), April 14, 2017, https://cinebibliophileblog.wordpress.com/2017/04/14/instafamous-a-report-on-chinas-micro-celebrities/.

- Allyson Chiu, “‘Snapchat Dysmorphia’: Patients Desperate to Resemble Their Doctored Selfies Alarm Plastic Surgeons,” The Washington Post, August 6, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2018/08/06/patients-are-desperate-to-resemble-their-doctored-selfies-plastic-surgeons-alarmed-by-snapchat-dysmorphia/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.9b888d796f02.

- For a brief but representative sample of many popular press publications connecting the selfie to questions of the gaze, see: Maria X. Liu, “Obstructing the Male Gaze in a Gaze-Dependent Culture,” Huffington Post, December 16, 2014, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/maria-x-liu/obstructing-the-male-gaze_b_6322936.html; “Women, Selfies, and The Male Gaze - What Really Happens When Girls Take A Selfie,” AMBmagazine.com, May 4, 2017, http://ambmagazine.com/women-selfies-male-gaze-really-happens-girls-take-selfie/; “Harvard Crimson: Girls Taking Selfies Is A ’Su | The Daily Caller,” accessed July 20, 2017, http://dailycaller.com/2017/03/07/harvard-crimson-girls-taking-selfies-is-a-subversive-feminist-act-against-the-male-gaze/; “Let Me Take a Selfie | Opinion | The Harvard Crimson,” accessed July 20, 2017, http://www.thecrimson.com/column/femme-fatale/article/2017/3/2/hu-let-me-take-selfie/; “The Selfie as a Feminist Act,” The Clayman Institute for Gender Research, accessed July 20, 2017, http://gender.stanford.edu/news/2014/selfie-feminist-act; “Putting Selfies under a Feminist Lens,” Georgia Straight Vancouver’s News & Entertainment Weekly, April 3, 2013, http://www.straight.com/life/368086/putting-selfies-under-feminist-lens; Ben Agger, Oversharing: Presentations of Self in the Internet Age (London and New York: Routledge, 2015).

- Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Visual and Other Pleasures, (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire England; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009): 14-30.

- Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review, Vol. 43, no. 6 (July 1991): 1241–99.

- Quentin Fottrell, “Instagram Users Admit They’ve Created the Most Narcissistic Social Network on the Planet,” MarketWatch, accessed July 20, 2017, http://www.marketwatch.com/story/beware-of-people-who-always-post-selfies-on-facebook-2015-07-16; Zoe Williams, “Me! Me! Me! Are We Living through a Narcissism Epidemic?,” The Guardian, March 2, 2016, http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/mar/02/narcissism-epidemic-self-obsession-attention-seeking-oversharing; “Hey, Guys: Posting a Lot of Selfies Doesn’t Send a Good Message,” News, January 6, 2015, https://news.osu.edu/news/2015/01/06/hey-guys-posting-a-lot-of-selfies-doesn’t-send-a-good-message; “Selfie Obsession: Are We the Most Narcissistic Generation Ever?” Telegraph, accessed July 20, 2017, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/11265022/Selfie-obsession-are-we-the-most-narcissistic-generation-ever.html; “Study Links Selfies To Narcissism And Psychopathy” Huffington Post, accessed July 20, 2017, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/01/12/selfies-narcissism-psychopathy_n_6429358.html

- Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Berkeley, Calif.: Grove Press, 2008).

- Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex (Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2011), 64; Sigmund Freud, “On Narcissism,” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud: Vol. XIV, trans. James Strachey. (London: London the Hogarth Press), 67-102.

- Freud, “On Narcissism,” 75.

- Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal, Vol. 40, No. 4 (1988): 520.

- Lauren Berlant, “Cruel Optimism: Optimism and Its Objects,” Differences, Vol. 17, No. 3 (2006): 20; See: Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2011).

- Ibid, 26.

- Ibid.

- Alexander R. Galloway, The Interface Effect (Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity, 2012), 136-138.

- Ibid, 124.

- “How to Be an Instagram Influencer For $300: A 2-Month Study,” Mediakix | Influencer Marketing Agency, August 4, 2017, accessed August 15, 2018, http://mediakix.com/2017/08/fake-instagram-influencers-followers-bots-study/.

- Peter Holley, “Soon, the Most Beautiful People in the World May No Longer Be Human,” The Washington Post, August 8, 2018, accessed August 15, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2018/08/08/soon-most-beautiful-people-world-may-no-longer-be-human/?utm_term=.49d6efbede7b.

- Ibid.

- Galloway, 2.

‘Speaking as’: Selfies and Cybertyping by Jenny Gunn is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License