Virtual Mass Ornament: Making Masses through Changed Spatial Perception in Handheld Digital Screen Culture In "K-Pop in Public" Videos on YouTube

Hyo Jung Kim

This essay discusses the merged perception of physical and virtual space manifested in a series of fan-made videos on YouTube and analyzes how such perception results in forming a virtually connected audience who perceives the physical reality through handheld digital screens and social media. For that purpose, this study will examine Siegfried Kracauer’s essay “Mass Ornament” and his book Theory of Film to discuss abstract perception of the physical reality shaped through film. Furthermore, this study will examine the readings of Natalie Bookchin’s video installation Mass Ornament in relation to Kracauer’s notion of mass ornament and to “K-Pop in Public” videos. Additionally, David Norman Rodowick’s The Virtual Life of Film provides an insight into understanding the screen culture in the 2010s, where digital cinema such as “K-Pop in Public” is grounded on; it is based on the handheld digital screen and platforms and software on it such as YouTube, Snapchat, Instagram, or Apple Stickers that connects image, information, and subjects, regardless of the physical spatiality. This essay attempts to argue that virtual spatiality matters more than physical space in the era of the digital screen. This argument will be examined through the case study of “K-Pop in Public” videos of the K-Pop group BTS’s performance “Not Today” on YouTube.

“K-pop in Public” videos on YouTube reveals a changed perception of blurred distinction between physical and virtual spaces, engendered by digital media. As a sub-genre of K-pop fan video, “K-Pop in Public” videos manifest the changed perception of the physical space in the users of the digital screen. In them, individual performers reenact the choreography of the song in the public space. The camera is focused on the performer, whether it is handheld or tripod-mounted. The one-on-one relationship between the performer and the camera is established as the video goes. As a result, while the pedestrians constantly pass by the dancing performer and are presented as if they were merely a backdrop of the video, the performer looks as if s/he is detached from the backdrop whereas the pedestrians are part of her/his physical reality. In this sense, the physical world in the “K-pop in Public” is presented as being connected to other spaces other than the physical one.

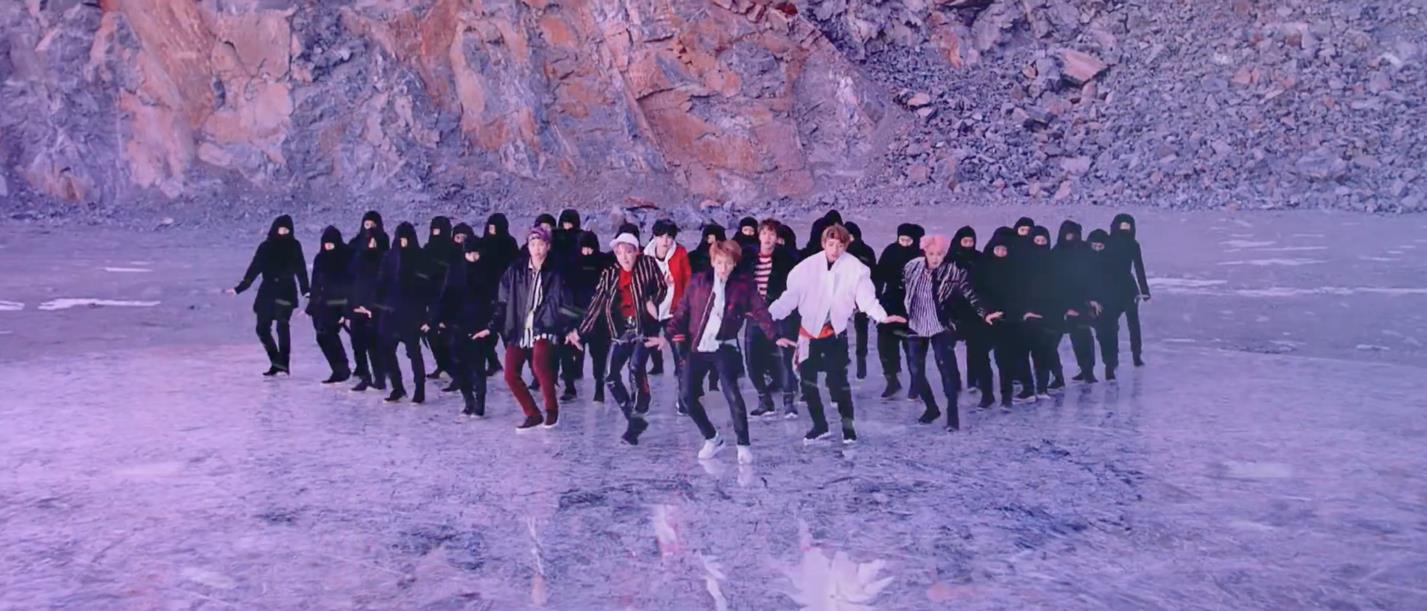

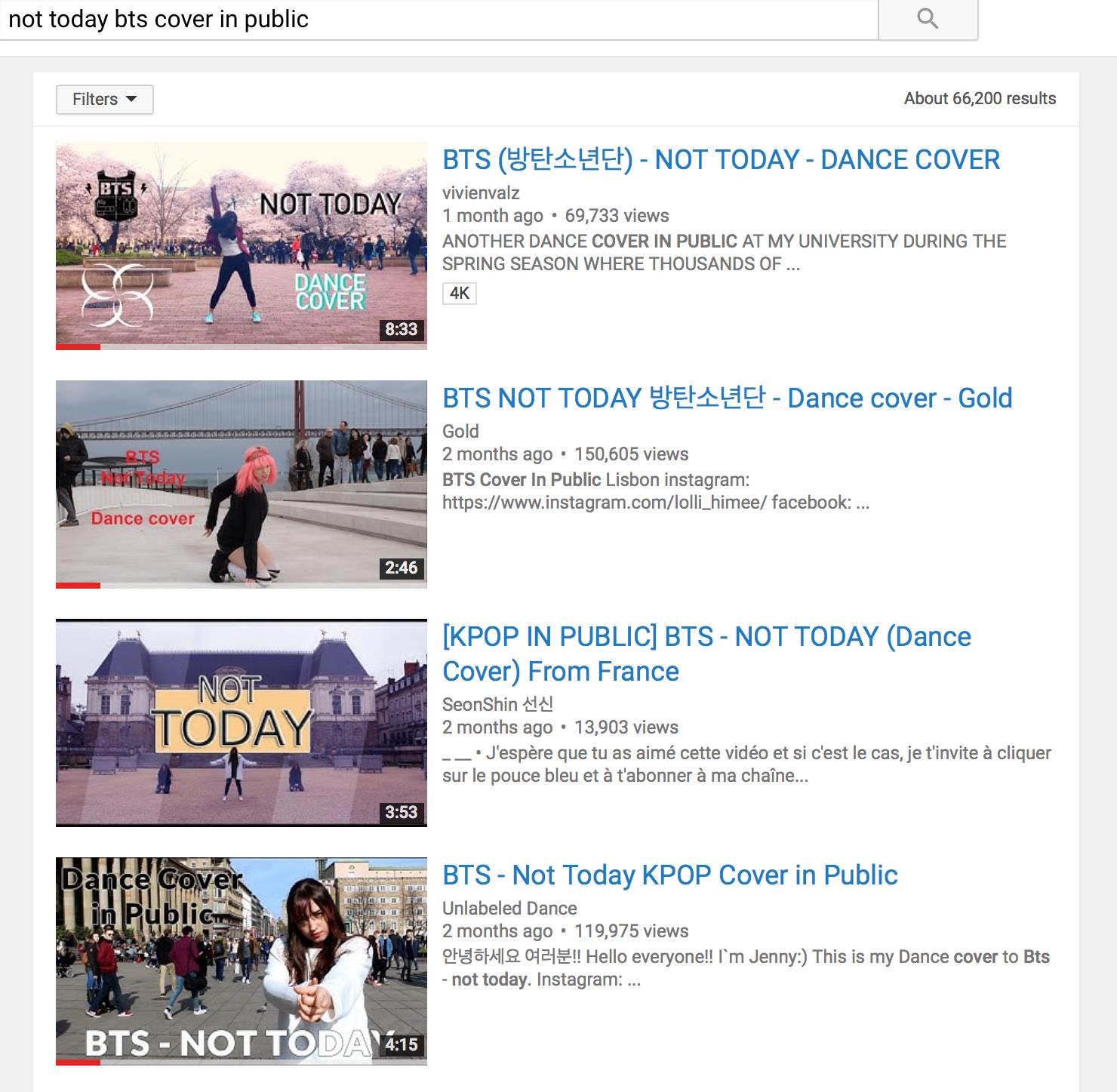

The perception of the virtual space in the physical space leads to the formation of the virtually connected masses who exist in different physical spaces around the globe. In “K-Pop in Public” videos, it is evident that the performer perceives her/himself as detached from the people in her/his physical space who are captured with them in the same scene. While precision group dance is one of the main features of K-pop, individual performers reenact the choreography alone in the middle of indifferent passers-by on the backdrop. In the case of “Not Today,” while the original choreography is mainly composed around precision group dance, (fig. 1) an individual cover dancer in “K-Pop in Public” videos choose a member of the group and reenact that person’s moves. Because of that, the dancer’s moves in “K-Pop in Public” videos look incomplete, (fig. 2)1 since the individual performer’s moves can only cover a part of the whole group’s dance. However, these seemingly incomplete dance moves are completed when considering the performers as part of the imaginary masses who are only virtually connected to collectively reenact the same dance moves. With such perception and participation across the virtuality, the performers in “K-Pop in Public” videos are part of masses on the virtual plane, regardless of their location in the physical space.

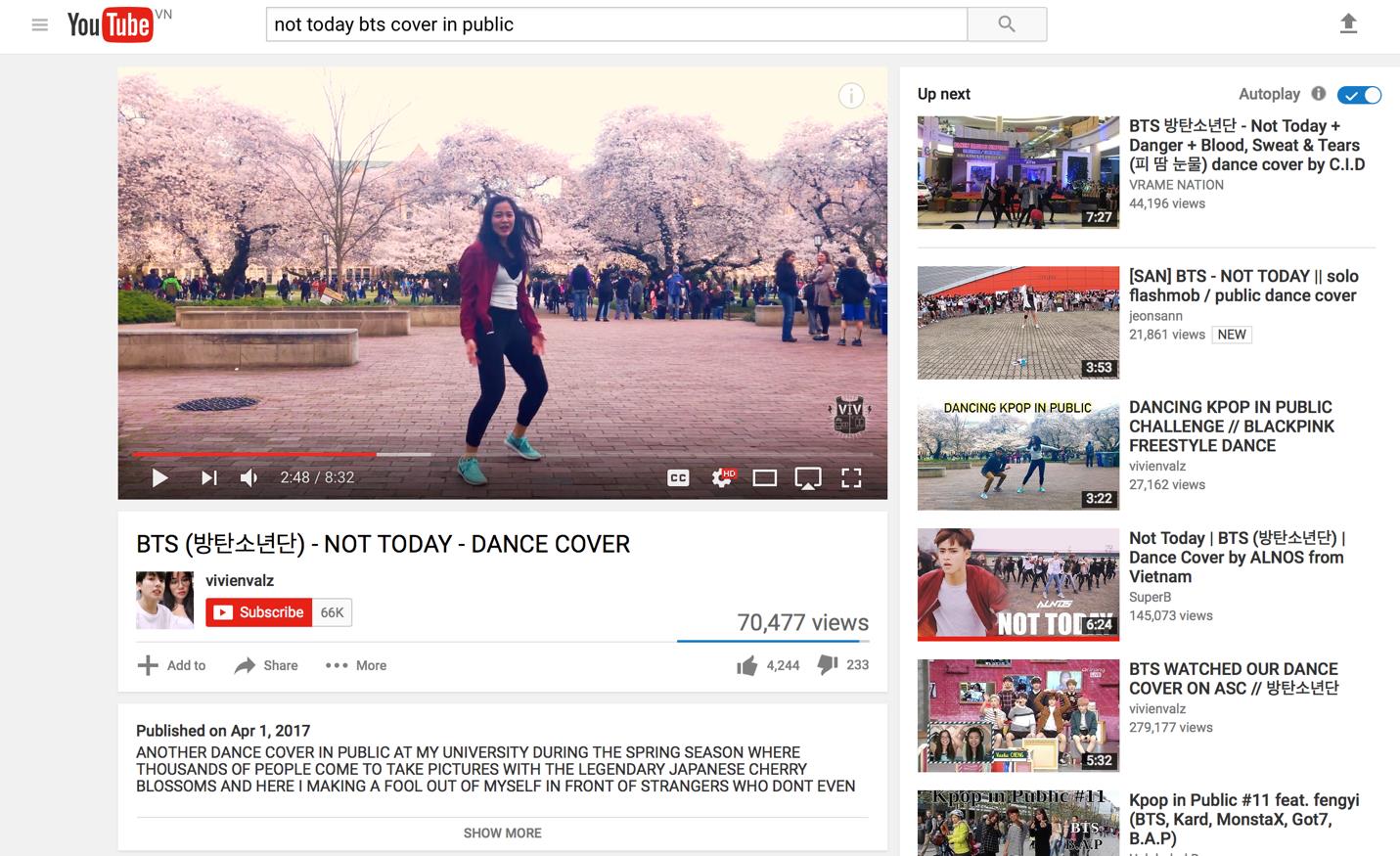

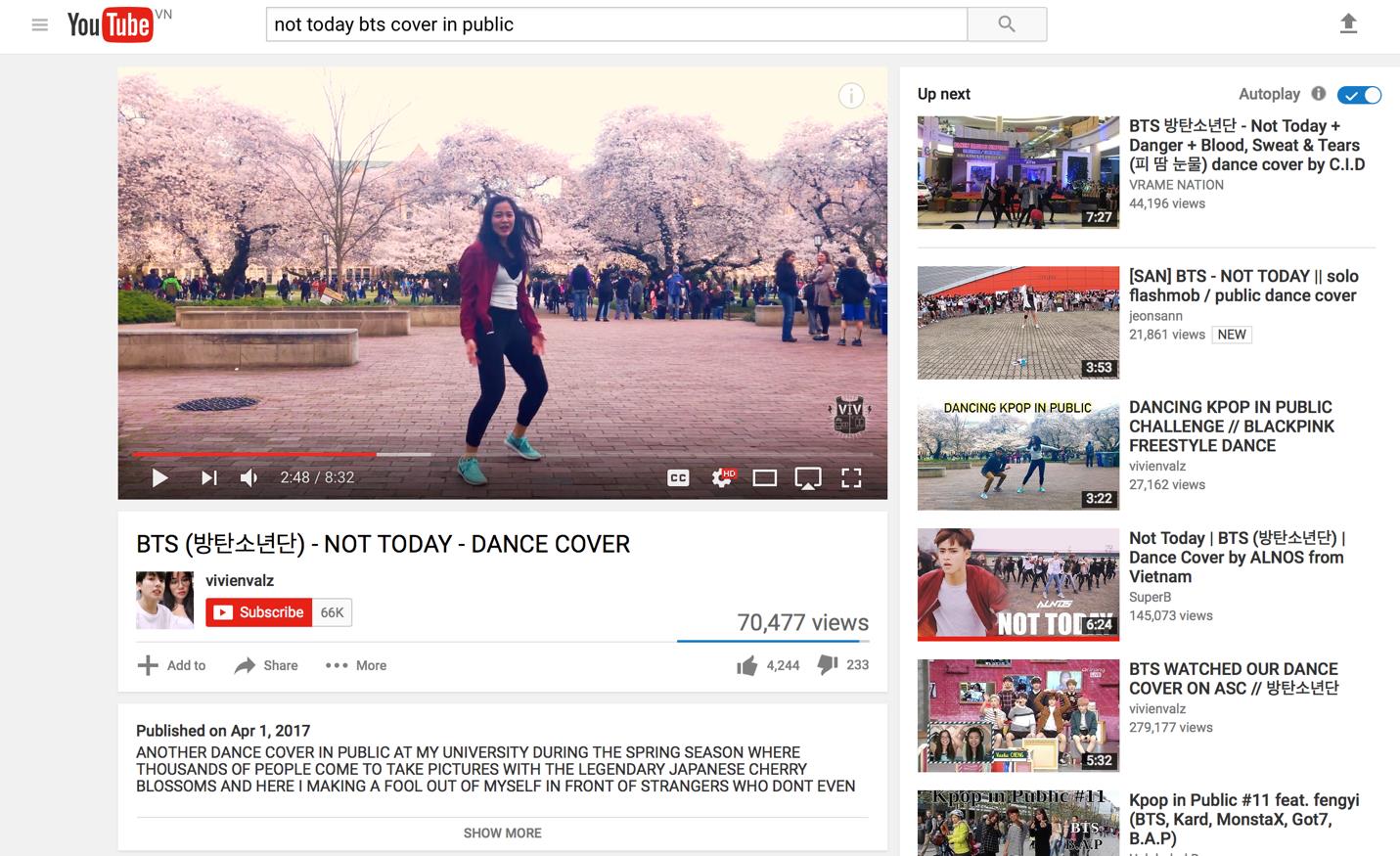

Additionally, the individual performers are virtually connected not only by the imagination of the performers but by the virtue of the algorithm of the digital platform. For example, when viewers on YouTube search the title of the song along with the keyword “K-Pop in Public,” the search result shows the list of videos made by individuals around the world who reenact the same choreography to the same song. (fig. 3) The individual performers in disparate physical spaces are virtually connected through the list of thumbnails in the search result, as well as in the videos. Moreover, YouTube shows the suggestion of similar videos on the sidebar. (fig. 4) While watching the selected video, the viewer is made to see the juxtaposed thumbnail image of similar videos. Either the viewer clicks the suggested thumbnails to watch the related videos or not, a suggestion of related videos also open up a way to form the virtually connected mass. This kind of virtual connection that transcends the physical space is suggested in the way that the digital media platform works.

As examined above, “K-pop in Public” videos show a changed visuality and perception of space in the digitally mediated world. The contrast of indifferent passers-by as the backdrop and the individual performer’s immersion in their dance moves creates an impression as if the passers-by and the performer exist in two different spaces, even though they exist in the same location in the filmed space. Filmed and watched mainly through handheld screens, it shows a way of changed perception of physical reality in the time of widespread use of handheld screens and cameras, as Anne Friedberg examines in her book The Virtual Window. Discussing how the world has been framed with different technologies, Friedberg points out that the screens in the twenty-first century have brought new systems of circulation and transmission. Now, the screens are “a pervasive part of daily experience.”2 Because of the way the viewers engage with the screen has changed,3 “our physically embodied and subjectively disembodied relation to the screen changes.”4

The digital screen is what made this kind of perception possible, expanding the limit of boundaries of the world. This is in line with Friedberg’s argument that “the limits and multiplicities of our frames of vision determine the boundaries and multiplicities of our world.”5 As such, virtual perception was introduced by the advent of the digital screen. Virtual understanding of the physical world manifested in “K-pop in Public” videos can be accounted for the widespread use of the digital screen. In particular, what is relevant is Friedberg's exploration of the tension between the material reality of built space and the dematerialized imaginary space that cinematic, televisual, and computer-based media provide.6 This kind of virtual perception of the physical space mediated through a digital screen is manifested in “K-pop in Public” videos.

The idea that the media’s intervention allows the viewer a new visual perception of their physical world was foreshadowed in Siegfried Kracauer’s writings. The mass ornament, an idea by Siegfried Kracauer in his essay “Mass Ornament” (1927) is an early example of the representation of dancing bodies on the screen and its relation to the notion of mass ornament. Kracauer analyzes the representation of dancing bodies as an abstract pattern by taking Tiller Girls, a group of militarily trained dancing girls7 as an example. In associating the legs of the Tiller Girls to the laboring hands in the factory,8 several times in the essay, Kracauer depicts how the dancing bodies are perceived as a form of abstraction. Tiller Girls are perceived no longer as individual girls but the cluster whose movements are demonstrations of mathematics:9 they are patterns that represent certain aspect of reality.10

This abstract perception of the physical world was made possible through the representation through the media, such as film and photography. Kracauer’s discussion on the mass ornament is built on the premise that the object should be analyzed beyond its surface-level expressions.11 Such a premise is also based on the presupposition that the surface level expression is somewhat dissimilar to what is not on the surface. Kracauer’s main purpose of the argument was to scrutinize the embedment of prevailing economic system in the abstract pattern and warn the readers of the danger that the production and mindless consumption of the ornamental patterns may divert the people from the imperative to change the reigning order.12 However, what is less strongly articulated here is the film’s ability to make this kind of perception possible. Because of the film and the screen that frame it, the image of dancing girls enters into a more complicated system of visual metaphors to be perceived as an ornamental pattern.

Kracauer further elaborated on the establishment of physical existence displayed on the screen, through the medium of film in his book Theory of Film. (1960) Kracauer exemplifies three types of cinematic subjects par excellence—namely the chase, dancing, and nascent motion—which can only be recorded by the motion picture camera.13 Kracauer’s discussion on dancing as a cinematic subject supports the merge of the imaginary and physical existence of dance movements as in Tiller Girls and in “K-pop in Public” dance videos. According to Kracauer, the mode of representation of theatrical dancing can either be indulgent in delivering completeness of the spectacle, or it can provide a selection of details in that they deviate from the original.14 While degrading the complete deliverance as “boring,”15 Kracauer advocates the film’s ability to lead the viewers to see the imaginary. In other words, the film and the screen that frame it make it possible to see beyond the real.

However, we are made to see the imaginary through the screen only by watching the real that is exhibited on it.16 Kracauer argues that in recording and exploring physical reality, the film exposes a vision into a world never seen before.17 However, such unprecedented vision is not from phantasmagoria. Kracauer pinpoints that a new kind of perception derives from the ordinary physical environment itself. From the representation in film, we can see what has remained largely invisible in our daily lives.18 Kracauer insists that material world is discovered with its psychophysical correspondences. In other words, we redeem the world from its “dormant state, its state of virtual nonexistence”19 through cinema. This is what the Kracauerian terminology “redemption of physical reality”20 refers to. The imagery of cinema takes us away from the objects and occurrences that comprise the flow of material life, although such “redemption” always ends up going back to the reality. “Film renders visible what we did not, or perhaps even could not, see before its advent,”21 Kracauer argues. That sort of new vision is not totally imaginary; it is a physical reality seen from a different light.

Weaving the multitude of layers of reality allows for seeing the different aspects of the familiar physical reality through the cinema. This is an active act of deconstructing and reconstructing the order of the reality. Kracauer points out that there are different dimensions of reality, and that we are not able to experience them equally. In other words, our physical reality consists of plural and different realities and we get to selectively experience a few of them. Kracauer’s discussion still applies to “K-Pop in Public” videos, a kind of digital cinema produced and circulated in the 2010s. As discussed, the performer dancing in the public space with indifferent passers-by because s/he perceives her/himself as belonging to different virtual spaces other than her/his own physical reality. Such perception was made possible through the digital screen culture and cinematic techniques, which was implied by Kracauer’s discussion.

Weaving22 the multitude of layers of reality allows for seeing the different aspects of the familiar physical reality through the cinema. This is an active act of deconstructing and reconstructing the order of the reality. Kracauer points out that there are different dimensions of reality, and that we are not able to experience them equally.23 In other words, our physical reality consists of plural and different realities and we get to selectively experience a few of them. Kracauer’s discussion still applies to “K-Pop in Public” videos, a kind of digital cinema produced and circulated in the 2010s. As discussed, the performer dancing in the public space with indifferent passers-by because s/he perceives her/himself as belonging to different virtual spaces other than her/his own physical reality. Such perception was made possible through the digital screen culture and cinematic techniques, which was implied by Kracauer’s discussion.

A contemporary mass ornament in a digitally mediated world is suggested by the American artist Natalie Bookchin’s single-channel video installation Mass Ornament (2009). Bookchin’s Mass Ornament created synchronized bodily movements by editing YouTube clips of homemade videos of people dancing alone in their rooms.24 Bookchin emphasizes that her mass ornament resembles Kracauer’s mass ornament, in that the representation of the dancing bodies of masses functions as the lens to critique the economic system. Whereas Kracauer’s mass ornament embodied characteristics of Fordism and Taylorism, Bookchin’s mass ornament embodies that of post-Fordism.25 On the post-Fordist aspects of her mass ornament, Bookchin explains that it embodies the notion of “smaller scale production by workers scattered around the world,” who are “linked by technology rather than an assembly line.”26 Such reading of the work that focuses on the medium’s ability to render the physical reality stemmed from Kracauerian reading.

Still, Bookchin’s mass ornament is different from Kracauerian mass ornament in its attempt to transcend the limitations of physical space by the virtuality of digital media. In her interview with Rhizome, Bookchin points out that Mass Ornament addresses the questions of “embodiment and publicness in the face of their seeming disappearance in the disembodied, isolated, screen-based virtual environment of the Web.”27 Produced in 2009, Bookchin’s Mass Ornament alludes to an aspiration to transcend the constraints of the physical space through the digital screen.28 The performers bounce off the walls and push against doorways, as if attempting to break out of the space they are encased in. Additionally, Bookchin’s editing29 that places individual performers on a same digital place is an attempt to test out the parameters of embodiment within the digital screen; collectively isolated individuals in their physical spaces are given a possibility of virtual interconnection.

Bookchin’s mass ornament and “K-Pop in Public” videos share differences and similarities in terms of the virtual interconnection of isolated individuals to form virtual masses. Produced in 2017, K-pop in public videos are grounded on a different terrain of digital media environment. The most significant difference between the two is the perception of the performer’s physical space. Because “K-Pop in Public” videos are shot in public places, the distinction between the individual and the masses is highlighted. However, since individual videos in Bookchin’s work is shot in private spaces, there is no counterpart to examine the sense of masses in individual performers.

Despite some differences, there are things in common as well. Bookchin articulates that the purpose of her work Mass Ornament is to create the image of people moving in sync, “as a part of something larger than their separate selves.”30 In such rhetoric resonates Kracauer’s original idea of mass ornament, as well as the virtual connection of individual performers in “K-Pop in Public.” In particular, Bookchin made a comment that situates her Mass Ornament in between the Kracauer’s mass ornament and “K-Pop in Public.” The style of the arrangement of multiple clips in a single row across the screen in Mass Ornament, Bookchin explains, mimics a chorus line but it also reflects the viewing conditions of YouTube.31 Bookchin points out the YouTube’s display of thumbnail images that links seemingly similar videos and adopts the method in a straightforward way in the editing of Mass Ornament, whereas in “K-Pop in Public,” the job is left to the imagination or the action of the viewers.

The genealogy of the mass ornament reflects the changes in media platforms and device technology and ensuing changes in user’s perception. This line of changes is culminated in “K-Pop in Public” videos. While Tiller Girls’ performance was seen through theater or television screen, and Natalie Bookchin’s Mass Ornament via the computer screen, “K-Pop in Public” videos are based on the handheld screen. In fact, “K-Pop in Public” videos are produced in an era when users are able to experience the screen from the closest distance and more frequently than ever before in the history of the screen. Also, the handheld screen has become not only the site of consumption but of production. This is in the same vein with David Rodowick’s comment on the possibility of the digital screen in his book Virtual Life of Film by saying that “the digital screen is no longer a passive surface.”32 This key feature of the handheld screen has been explored and expanded by different media platforms and software so that the users of the handheld screen could actively cultivate the unprecedented perception of the physical world.

Particularly, the changed perception of the physical world in handheld screen users has been prompted by the popularity of the media platforms that facilitated the production of user-generated digital images. Haptic technology and its embedment in the screen of personal computers and mobile phones began to blur the boundary between the physical and virtual perception of its user, since physical movement is directly converted into the traces of digital image on it. Media platforms such as Snapchat and Instagram accelerated the blurring. Established in 2010, Snapchat offered the service to share ephemeral photographs, based on smartphones. One of the popular features of Snapchat is to provide brush and sticker tools so that users can decorate the photos they took. (fig. 5) Instagram, too, launched the similar feature, “Story” in 2016.33 Not only users are given options to change the filters and calibrate the tone or saturation but they are now able to make a virtual drawing, inscribe a text, or applying pre-made stickers over the picture they just took. This option has been explored via digital screen, which has brought about the “symbiosis of the digital and the analogical.”34 Thanks to such media platforms, more than 166 million people on snapchat35 and 700 million users of Instagram36 learn and get used to such way of seeing and producing.

Software also serves to spread the technology that facilitates the perception mixing physical and virtual spatiality. One example is found in Apple’s promotion video for an iPhone feature. The video “iPhone 7 – Sticker Fight – Apple” video37 is an advertisement that promotes iMessage sticker packs. The video shows the daily lives of a younger generation in a city where they can slap on iMessage stickers to whatever situation they face in physical space. For example, on the body of a man talking on the phone, one passer-by applies a speech bubble sticker that says “blah blah blah,” while another passer-by applies a sticker of a man with the beard, which looks like the man who is talking on the phone. (fig. 6) The message of the video is clear: the boundaries of the physical world and virtual world can merge. As such, the digital media platform or software that actively engages users in manipulating images on their fingertips has redesigned their perception of the distinction between physical and virtual space.

On the digital screen, clear boundaries of the physical space are blurred. Because of such features of the digital screen, dancers in “K-Pop in Public” video can be united as virtually connected masses despite their physical location in different parts of the world. As in “K-Pop in Public” videos, the performer and the passers-by exist on the same geographical location in the physical world. Without the mediation of the digital screen, both are considered to occupy the same space and time. However, when their images are mediated through the digital screen, both parties’ time flows differently and eventually detach them from physical spatiality. For the performers in the “K-Pop in Public” videos, their images are sorted, organized as digitized information and connected to the same type of information—other performers in other similar types of videos. In this way, the individuals become a part of virtually connected masses through the digital mediation of their images on the handheld digital screen.

List of Figures

Fig. 1 A scene from the music video “Not Today” by BTS that shows precision group dance.

Fig. 2 K-Pop in Public dance cover of “Not Today” on a street in Germany. Individual performer’s reenactment of group dance seems incomplete.

Fig. 3 Search result of “K-Pop in Public” videos of BTS’s “Not Today” cover dance videos on YouTube.

Fig 4. While a video is being played, a suggested list of similar videos is shown on the sidebar.

Fig. 5 Instagram Story enables users to decorate digital photographs. In this example of a use of Instagram Story, the banana in physical space functions as the mouth and the digital hand drawing that looks like a pair of eyes completes the smiley face.

Fig. 6 A scene from Apple’s iMessage sticker promotion video. Image of physical reality and virtual image of stickers are merged.

Works Cited

- YouTube video by username Unlabeled Dance, “BTS - Not Today KPOP Cover in Public” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OU-VGbt3Q6E. (Accessed May 17, 2017)

- Friedberg, Anne. 2006. The virtual window: from Alberti to Microsoft. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 6.

- “From the distant, large cinema screen with projected images; the closer and light-emanating television screen; and the even closer computer screen, one that we put our faces very close to, often touch, one that sits on our laps or in our beds.” Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. This is a visual corollary of Wittgenstein's epigram, "The limits of my language are the limits of my world"

- Ibid., 21.

- A group of militarily trained dancing girls named after the Manchester choreographer John Tiller. Introduced in the late nineteenth century, the troupe was hired in Germany by Eric Charell, who from 1924 to 1931 was the director of Berlin's GroPes Schauspielhaus theater and whose revues and operetta productions were the forerunners of today's musicals. Kracauer, Siegfried, and Thomas Y. Levin. 1995. The mass ornament: Weimar essays. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 356, note 1.

- Ibid., 79.

- Kracauer, The mass ornament, 75.

- Ibid., 85.

- Ibid., 75.

- Ibid., 85.

- Kracauer, Siegfried. 1960. Theory of film; the redemption of physical reality. New York: Oxford University Press, 41-42.

- Kracauer, Theory of film, 42-43.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 43.

- Ibid., 299.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 300.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 300.

- Ibid., 308.

- Kracauer, Theory of film, 297.

- Kane, Carolyn. “Dancing Machines:An Interview with Natalie Bookchin,” Rhizome, http://rhizome.org/editorial/2009/may/27/dancing-machines/ (MAY 27, 2009 –)(Accessed May 05, 2017)

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Kane.

- Ibid.

- The choreography of Mass Ornament works on several levels. First, you have selected clips according to specific movements. Second, they are composed within the installation according to a particular themes, and third, the overall “compilation” of dance clips tells a story: the images set an empty stage (often in the bedroom), the dancers enter the stage, tease a bit, do their thing, and through your editing, a meta-level of choreography emerges. Kane.

- Kane.

- Ibid.

- Rodowick, David Norman. 2007. The Virtual Life of Film. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 139.

- Constine, Josh. “Snapchat growth slowed 82% after Instagram Stories launched,” Techcrunch.com https://techcrunch.com/2017/02/02/slowchat/ Feb 2, 2017. (Accessed May 17, 2017)

- Rodowick, 139.

- "Number of daily active Snapchat users from 1st quarter 2014 to 1st quarter 2017 (in millions),” https://www.statista.com/statistics/545967/snapchat-app-dau/ (Accessed May 17, 2017)

- "Number of monthly active Instagram users from January 2013 to April 2017 (in millions),” https://www.statista.com/statistics/253577/number-of-monthly-active-instagram-users/ (Accessed May 17, 2017)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XBfk1TIWptI, posted by Apple on March 13, 2017. (Accessed May 05, 2017)

Virtual Mass Ornament: Making Masses through Changed Spatial Perception in Handheld Digital Screen Culture In "K-Pop in Public" Videos on YouTube by Hyo Jung Kim is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License