Time and Time Again: The Cinematic Temporalities of Apichatpong Weerasethakul

By Daniel Grinberg

Introduction

Throughout the oeuvre of Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, conceptions of time are a vital element of both the storytelling and the stories themselves. The formal manifestations and thematic components of time mutually reinforce each other in ways that recall such avant-garde films as Last Year At Marienbad (Alain Resnais, 1961) and Testament of Orpheus (Jean Cocteau, 1961) and that increasingly occur in contemporary mainstream and independent cinema like Memento (Christopher Nolan, 2000), 2046 (Wong Kar-Wai, 2004), and Source Code (Duncan Jones, 2011). However, what distinguishes Weerasethakul’s work is the intention that underlies these temporalities. Namely, I argue that Weerasethakul, as the writer and director, valorizes alterity and catalyzes viewers to reevaluate repressive societal norms through a multi-nodal critical heuristic of alternative and non-normative temporalities.

Since Weerasethakul received the Jury Prize for Tropical Malady (2004) at the Cannes Film Festival, his stature has steadily risen among scholars and cinephiles alike. His win of the festival’s top prize, the Palme d’Or, for Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) has only accelerated the pace of scholarship regarding his work. Notably, the first collection devoted to the director, Apichatpong Weerasethakul (2009), edited by James Quandt, includes Quandt’s survey of the major motifs and techniques in Weerasthakul’s works.1 Ji-Hoon Kim has also insightfully drawn aesthetic and thematic linkages between Weerasethakul’s features and multimedia installations.2 However, while both writers consider issues of temporality tangentially in their discussions, no one has yet identified it as a primary organizing principle for analyzing the director’s eight feature films to date.3 Nor has anyone articulated the multifaceted ways that Weerasethakul employs temporal strategies, through processes of formal experimentation and tied to distinct identity categories, to heuristically nudge viewers into recognizing and challenging their own discriminatory preconceptions. This article will address these lacunae while simultaneously using the lens of temporality to provide new interpretative vantages onto the films.

Formal Manifestations of Temporality

Fractured NarrativesThe most conspicuous formal representation of temporality, and the one to garner the most scholarly notice to date, is Weerasethakul’s use of fractured narratives. As early as his debut feature, Mysterious Object At Noon (2000), he has subverted structures of linear progression. He accomplishes this partly by employing what Gérard Genette calls anachronies, sequences of story and discourse where the chronological presentations of the two elements are in different orders.4 But in addition to the common technique of analepsis, or flashback, and the rarer prolepsis, or flash-forward,5 there are also ruptures that replace teleological progress with a more open-ended and inclusive approach that Weerasethakul refers to as a “liberation from expectation… and the known pattern of time presented in film.”6

This act of liberation first materializes in Mysterious Object, an unscripted semi-documentary, as a traumatized woman recounts a harrowing tale of her father selling her as a child. Abruptly, Weerasethakul asks her to tell a fictional tale instead, with the film adopting an “exquisite corpse” structure.7 He then asks people across Thailand to expand upon the woman’s fable and films enactments of the versions they relay. The settings of these versions, as diverse as the locals he selects, range from a modern present to a mythic, ahistorical realm. Lacking definitive beginnings or endings and featuring rapidly shifting timelines, this multitude of loosely linked stories is an example of what David Herman calls polychrony. Polychrony, as this film evinces, “exploits indefiniteness to pluralise and delinearise itself,” thus upholding the utility of subjectivity.8 No version of the multivalent fable is presented as correct or preferable; rather, each is validated as another credible perspective from which to investigate the characters and storytellers.

Tropical Malady, Weerasethakul’s second film, also employs a radically fractured narrative—this time, bifurcated. The first part explores the relationship of a soldier, Keng, and his male love interest, Tong. Eschewing the trajectory of a conventional plot, it shows glimpses of their daily lives. After fifty-eight minutes, the film suddenly cuts to an interstitial black screen and introduces new opening credits, a shift that is “not chronologically or causally justified by its diegetic elements.”9 The second part, which follows a soldier hunting a shape-shifting tiger spirit, also lacks the characteristics of a conventional plot. Beyond using the same actors for these main roles, Weerasethakul does little to connect the segments or explain the disjunction between the naturalistic contemporary setting and the atemporal and supernatural one. Thus, in order to reunify the film, viewers must draw their own connections among the radical differences and observe, as Ji-Hoon Kim points out, that “the temporal relationship between the two halves is interdependent and cross-contaminating.”10 Ultimately, the contradistinctions of these halves help reinforce the other’s cruciality and thus, cleverly symbolize the nature of romantic coupling.

A similar bifurcation splits Syndromes And A Century (2006), which presents a recurring story set in two diacritical milieux. The first depicts two doctors working at a small rural hospital, while the second depicts the same doctors in a modernized urban medical facility. The repetition of conversations and scenes, most prominently in the hiring interviews that Dr. Toey conducts with Dr. Nohng at the beginning of both scenarios, emphasizes that these are compossible accounts rather than conclusive realities. In the first version of the interview, the camera fixes on Nohng’s face with a point-of-view shot, as the applicant struggles to answer a set of evaluative questions. The second version reverses the perspective, displaying how Nohng would see Toey, while adding a few new revealing questions and bits of biographical data. Their dialogue also playfully spotlights the themes of reiteration and variation, such as when Nohng discloses that he became a doctor to avoid “the same old faces,” preferring “to see faces come and go.”11

|  |

Dual perspectives and milieux in Syndromes

For Gilles Deleuze, these scenes would exemplify a transgressive kind of repetition. Deleuze has argued that the failure to exactly replicate an antecedent indicates a break in the oppressively fixed patterns of social order and frees time from the cyclical modes that subjugate content.12 In that sense, the minor alternations are provocations to question purportedly absolute truths and cultural norms, and another way in which Weerasethakul’s differences become subversive.

In his penultimate feature, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, Weerasethakul returns to the polychronic form. The work centers on Boonmee, an old Buddhist man dying of kidney disease, and intertwines contemporary scenes of his life with surreal visions of his reincarnations. It is impossible to determine whether the latter are prolepses or analepses or to pinpoint what Genette calls the reach, or chronological distance, from the primary narrative.13 Even within the present, the introduction of fantastic elements such as Huay, Boonmee’s wife returning as a ghost, and Boonsong, his son who has transformed into an enormous, hirsute Monkey Ghost, disturbs the possibility of a standard temporality. At one point, Huay remarks, “I have no concept of time any longer,” and because her materialization is preserved at the age of forty-two, her younger sister, Jen, now appears to be older than her. As Jacques Derrida elaborates, because a ghost is a paradoxical figure that is “neither soul nor body” and neither dead nor alive, it exists beyond time and ontology as a present figure bound to the past.14 As this “spectral asymmetry… de-synchronizes [and] recalls us to anachrony,” these untimely icons induce viewers to reconceive the potentialities of existence both inside and outside of this cinematic universe.15

A second fracture occurs at the end of the film, when two versions of the characters Roong, Jen, and Tong simultaneously appear in the same room. One set of the trio diverges to go to a karaoke bar, while the other remains in place, watching television. This conflation of narrative threads not only undercuts the prospect of a unilateral, determinant ending, but asks viewers to move backward through the film, reassessing every choice as the visualized one standing in for many invisible and unactualized others.16 Deleuze has explained that mirror images also generate skepticism, because viewers can never differentiate between the doubles with certainty.17 Thus, the multivariate elements of this world, lacking both fixed identities and chronologies, pose another challenge to regnant power structures, with a narrative that prompts viewers to question the authority of narrative itself.

Doubled trios in Uncle Boonmee

In addition, Weerasethakul employs the technique of the long take to connect temporality and difference. That practice is central to his filmmaking and situates him in lineages of contemporary Asian cinema (Tsai Ming-Liang, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Jia Zhangke, et al.), European arthouse (Andrei Tarkovsky, Chantal Akerman, Béla Tarr, et al.), and Italian neorealism (Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, et al.). By drawing out the duration of shots toward isochronic time, with an average shot length of thirty-seven seconds,18 and utilizing relatively few ellipses, Weerasethakul succeeds in humanizing his characters. The unhurried style in which they are presented, with both their dialogue and actions untethered from the impetus of narrative efficiency, makes them feel more like individuals with unique traits than like archetypes.

Weerasethakul’s frequency of extreme long shots of natural landscapes or cityscapes, whose literary equivalent Genette refers to as descriptive pauses, also accomplishes a consequential purpose beyond its cinematographic effects. Brian Henderson points out, “Even if no action occurs in this shot or in this setting, the time devoted to them builds expectations for action to come; they too are ticks on the dramatic clock. Indeed few things build more expectancy than silent shots of objects in a narrative film.”19 Simultaneously, the pacing reminds viewers that they are occupying a separate matrix codified with its own parameters, which invites viewers to readjust their expectations. As Weerasethakul states, “[People ask] why is your shot is [sic] too long? I say no, it’s not long for me, it’s just that my time is different from your time. Maybe after awhile… you can get to know about my time.”20

The long takes, including the tracking shot of Dr. Wan paralyzed by carbon monoxide in Syndromes and Min’s voiceover of a letter set to footage of vegetation in Blissfully Yours (2004), also often exemplify what Deleuze terms the time-image. A break from the movement-image, which captures a more literal, spatially based “mobile section of duration” associated with pre-World-War-II cinema and Hollywood blockbusters,21 the time-image achieves a direct representation of time. By introducing aberrant perceptions of movement, and eroding the rational, quantifiable temporal linkages between shots, it becomes indiscernible, fluctuating between the past and present and the virtual and actual.22 The time-image then puts truth into crisis, Marcia Landy explains, by “throw[ing] into doubt the nature of belief, producing, but not guaranteeing, the possibility of thinking otherwise and conceptually from the outside.” 23 Therefore, the time-image also ruptures conventional logics of spectatorship and the affective experiences of cinematic life-worlds.

The opening credit sequence of Syndromes offers one dramatic iteration of the time-image, signaling Weerasethakul’s liberatory intent at the film’s outset. A hand-held shot follows Drs. Toey and Nohng and an assistant, Koh, outdoors, but when the characters turn down a path, the camera instead dollies forward and freezes on a long shot of a field and distant house. This unchanging framing remains onscreen for over two minutes, even while the sound continues to record the trio’s conversation. Although Toey, Nohng, and Koh are walking farther away, the volume of their interaction does not change. Promoting the aberrant over the rational, this incongruity of the visual and aural demonstrates Deleuze’s assertion that the time-image foregrounds topology and time over space and movement.24 To further puncture the illusion, the actors then break character and comment on the timeline of the filmmaking process. Nantarat Sawaddikul, who plays Toey, observes that they have been shooting “the same scene over and over” and Nitipong Tintupthai, who plays Koh, responds, “It’s only been five takes.” Appropriately, this metafilmic moment occurs as the credits for the film editor, cinematographer, and Weerasethakul as producer, writer, and director are superimposed onscreen, emphasizing Syndromes’ temporality as a malleable construction and the fluidity between the real and virtual chronologies.

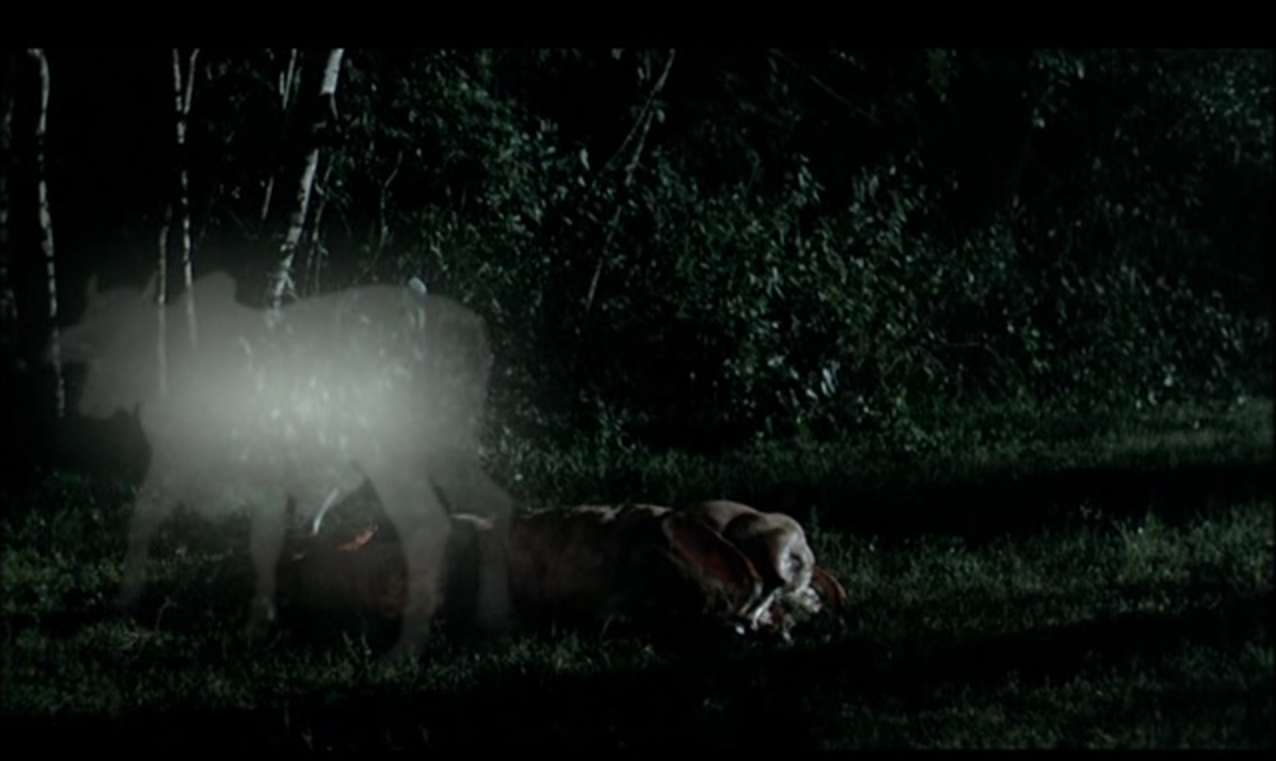

Another significant time-image occurs in Uncle Boonmee, when the titular character recounts a dream.25 “Last night, I dreamt of the future,” he tells Jen and Huay. “I arrived there in a sort of time machine.” This dystopic vision begins unexpectedly with a still image of a soldier in camouflage leading a leashed Monkey Ghost through a field. This shot lingers uncomfortably, immobilizing both the viewers and the prisoner. Boonmee explains that the governing authority can make “past people” disappear by shining a light on them and projecting images of them throughout time on a screen, a disorienting negation of the enduring, memorializing nature of film and digital media. The following images from Boonmee’s dream are also disorienting, because they appear out of sequence and the depictions of movement and stillness are equally frozen, stripping the figures of their agency.

This abeyance of continuous motion and flow of time produces an effect comparable to instantaneous photography, a medium that reached its height in the 19th century. Unlike the pastness of a photograph, which commemorates an already completed action, both instantaneous photography and Boonmee’s dream sequence are inherently set in the future tense, because they freeze actions before their completion.26 For viewers, this disjunctive phenomenon can be troubling, because it reveals what Mary Ann Doane identifies as the “sudden vanishing of the present tense, splitting into the contradiction of being simultaneously too late and too early.”27 Weerasethakul actualizes this temporal oblivion by framing the dream as the remembrance of an un-yet-realized contingency and situating present viewers in contrast to both the future soldiers and past people. Thus, by rendering viewers as helplessly out of time as Boonmee, the director triggers a “posthumous shock”26 to catalyze them to imagine their own possibilities of agency and mobilization more expansively.

One image in the sequence, showing a group of soldiers posing with a captured Monkey Ghost, impels an especially traumatic shock. It is apparent that the monkey suit is a costume, giving this virtual figure an oneiric, uncanny, and even humorous quality, unlike the soldiers and grave subject matter. The young men in uniform, some smiling naïvely beside their prisoner, also recall the detainee abuses of Abu Ghraib and infamous photographs of Specialists Lynndie England and Charles Graner. For American viewers, these soldiers may trigger connections to current and past institutional abuses like the operation of the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base and extralegal black sites, internment of Japanese-Americans, and enslavement of African-Americans. Thai viewers may instead draw local parallels, like the violent governmental crackdown that divided their country from 2008 to 2010, clashes against Muslim separatists in the 2000s,29 or, as Boonmee contemplates his participation in, the killing of Communist guerillas from the 1960s to the 1980s.30 No matter which associations of militarism this shot conjures, the weighty pasts, both cinematic and historical, exist in an uneasy circuit with the present. Thus, through this problematizing time-image, Weerasethakul affirms that ideological, ethnic, and sociocultural differences cannot simply be ‘disappeared’ as a means of cleansing troubling national histories.

Posing with the Monkey Ghost prisoner

Identity Temporalities

Problem BodiesTo more fully comprehend the alternative temporalities of Weerasethakul’s oeuvre, it is also necessary to think through the multiple alternative and marginalized identities of both the director and the characters he depicts. Drawing on the theorizations of prior scholars of temporality, I suggest that these frequently stigmatized cultural statuses evoke their own internal conceptions and logics of time, which I call identity temporalities. As I will demonstrate, these identity temporalities shape the textual representations and the filmic structures these representations inhabit as another key dimension of Weerasethakul’s critical heuristic.

Significantly, each of Weerasethakul’s works emphasizes a range of outsiders functioning at the periphery of social order, including the very young and old, the sick, and disabled. In particular, there are frequent manifestations of corporeal alterity, which Sally Chivers and Nicole Markotić term the problem body,31 including Min’s dermatological affliction in Blissfully Yours and the elderly Boonmee’s kidney disease in Uncle Boonmee. Though mainstream cinema typically effaces or pathologizes individuals with problem bodies, they receive prominent screen time and respectful, equitable portrayals of their differences in Weerasethakul’s films.

That commitment to egalitarianism is apparent throughout Mysterious Object. The director’s interview subjects encompass a cross-section of regional origins, ages, and abilities, ranging from a group of elderly women to a pair of deaf schoolgirls communicating in sign language. The storytellers receive equivalent amounts of screen time, and because of the ‘exquisite corpse’ structure, they are also all integrally included as creative agents within the unified framework. Most critically, the film does not flatten their differences into homogeneity, instead registering the singularity of their outlooks.

Situated among the many oral storytellers, the deaf schoolgirls’ segment also perceptibly indexes the temporal difference that these narrators’ disability creates. As studies of sign language show, deaf communication relies more on paralinguistic signals like tempo, rhythm, and pause mechanisms.32 Because signs take twice as long to produce as words, sign language also emphasizes rapid shifts of facial expressions to speed up expression.33 Thus, visualizations of Deaf culture like this one allow unexposed viewers to recognize and consider these temporal variations.

Telling their story in Mysterious Object

Weerasethakul’s inclusion of problem bodies also challenges the false notion of fixed identities, and, consequently, of fixed temporalities. Syndromes, which is set in two medical facilities and centers on the interactions of doctors and patients, is particularly focused on patiently and painstakingly documenting the debilitating effects of illness. In one consultation, an old, sick monk complains of having sore legs and aching joints. In the military wing of the hospital, a legless veteran also hobbles down the hallway and crippled soldiers learn to walk on prosthetic limbs. These representations gesture toward some of the many ways that aging and serious illness can drastically reconfigure experiences of temporality. For instance, formerly straightforward tasks like walking now require the soldiers more time and effort to accomplish, compelling them to reevaluate normative expectations of ability.

For Petra Küppers, these onscreen encroachments of aging, sickness, or disability also locate time within viewers’ bodies. Images like these, she notes, convey the message that “if you are young now, you will be something like this in the future. If you are masculine now, you will be feminized by the indignities of medical treatment. If you are TAB, temporarily able bodied…, you have to face up to the implications of the T.”34 Thus, beyond being signifiers of mortality and loss, problem bodies undermine hegemonic standards, because they remind viewers that “everyone who does not die suddenly will become a member of the subordinated group.”35

In Syndromes, the primary character Dr. Nohng acutely embodies the risk of verging on sickness. Though he outwardly appears healthy and youthful, and has not yet been diagnosed as sick, he reveals that he is carrying the gene for alpha thalassemia, a rare hematological disorder. His liminal status shows that neither he nor the medical establishment can definitively foresee if and when the condition will manifest. Indeed, every person, no matter how seemingly invulnerable, shares some indeterminate risk of becoming mentally or physically ill or incapacitated at any moment. Paradoxically then, the demarcations of difference that Weerasethakul’s problem bodies present also underscore the qualities mutual to every character and viewer—the universal fragility and precarity of the human condition.

Queer temporalityThe narrative centrality of outsiders also heavily factors into Tropical Malady and The Adventure of Iron Pussy (Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Michael Shaowanasai, 2003), whose protagonists are a homosexual couple and a gay transvestite respectively. Given the tendency of Thai directors to self-censor, the harsh restrictions of Thailand’s Censor Board,36 and the country’s discriminatory social sanctions against queer sexualities, these representations transgressively visualize underrepresented communities for worldwide audiences. Putting these individuals ‘out there’ in an open, unmitigated fashion is, for Diana Fuss, a way to enable them “to no longer be out;… to be finally outside of exteriority and all the exclusions and deprivations such outsiderhood imposes. Or, to put it another way,… to be in—inside the realm of the speakable, the visible, the culturally intelligible.”37

Furthermore, these characters’ practices reflect another conception, queer temporality, that opposes traditional modalities of organizing time. (The polysemic concept of queer is a particularly apt descriptor of the filmography of the openly gay Weerasethakul: its radical and irreducible strangeness, its reclamation and recentralization of disregarded voices, and its destabilizations of gender and sexuality norms.) Jack Halberstam has suggested that queer time foregrounds the potentialities of lives that operate on alternative schedules and are based on divergent social and economic priorities.38 Especially in countries like Thailand, where gay marriage and gay adoption remain illegal, this non-normative temporality derives from “futures [that] can be imagined according to logics that lie outside of those paradigmatic markers of life experience—namely, birth, marriage, reproduction, and death.”39

Halberstam’s theorization informs my reading of Tropical Malady as a manifestation of queer space and temporality. Weerasethakul, forgoing the presence of any major paradigmatic markers, fills the film’s first half with small, quotidian moments of Keng and Tong’s interactions. Tong is portrayed as the more passive and reticent partner, lacking experience and comfort with his sexuality. In one scene, Keng asks Tong to accompany him to the market and his military camp, sites where many people would see them together. Tong responds that he’s afraid he’ll “look foolish” in town and circumspectly adds, “I’ll go another day when I’m free.” The only intimate encounters that they share occur in the darkness of a movie theater, while immersed in an onscreen reality, and alone in the wilderness. Thus, I read the mythic second half, set in an otherworldly and primal jungle, as Tong’s creation of a queered space and temporality in which he can finally consummate his atavistic desires.

Tropical Malady’s queer, otherworldly temporality

The Adventure of Iron Pussy, co-written and co-directed by the film’s star Michael Shaowanasai, also plays with notions of queer time. It centers on a crime-fighting kathoey, a recognized but not legally accepted intermediate third gender in Thailand that now refers almost exclusively to transgender biological males.40 Perhaps due to the general tolerance of kathoeys in Thai culture, Weerasethakul’s and Shaowanasai’s film can frame Iron Pussy as a heroic and triumphant figure, unlike tragic transgender Westerners like Brandon Teena in Boys Don’t Cry (Kimberly Peirce, 1999) or Lola in All About My Mother (Pedro Almodóvar, 1999).41 The character’s spontaneity, mutability, and talent for reinvention allow her to break from her disreputable past as a go-go boy and “[a]n actor with a bad life” and perform the complex simultaneity of roles required of a secret agent. Her unapologetic queerness, rather than precipitating her downfall, also enables her success when conventional agents “could do nothing, find nothing,” according to the bureau’s leaders. They insist that she is the ideal choice for the mission, because its target, Madame Pompadoy, likes “unique, beautiful things,” and “no doubt, [that’s] you.” By contrast, the film’s villain, Tang, is rigidly fixed in his conceptions of gender roles and temporality. When Iron Pussy, disguised as the maid Lamduan, asks Tang if he contemplates their future, he replies, “Yes, I think about our future. I want to have someone special who does my laundry and cooks for me.”

However, the consciously retro style in which Iron Pussy is told, a campy homage to 1970s Thai melodramas, musicals, and action films, full of fantastic fight sequences and overwrought plot machinations reminiscent of soap operas, subtends the illusory nature of its empowerment. While there are kathoeys who become renowned and wealthy entertainers, many others spend their life savings on gender reassignment surgery only to end up as prostitutes42 or face exclusion from legal protections and the private-sector job market.43 Tellingly, while Iron Pussy evokes the glamorous intrigue through the generic signals of escapist 1970s cinema, the film’s least campy moment reveals her unnamed male persona mundanely working the graveyard shift at a convenience store to survive. Thus, by stylistically blurring the boundaries between past and present, akin to how a kathoey blurs distinctions of gender and sexuality, Weerasethakul and Shaowanasai hint at the pervasive reality of inequality lurking behind the fantasy.

Buddhist temporalityThe influence of Buddhist temporality, and how Weerasethakul incorporates it to promote social equality, are two other central aspects of his filmmaking. On one hand, it may seem ethnocentric to frame Buddhist conceptions as alternative, given that over half a billion people in Asia are Buddhist44 and the director’s homeland, Thailand, has a population that is nearly 95% Theravada Buddhist.45 However, the exhibition of Weerasethakul’s features primarily occurs at Western film festivals and arthouse theaters. With only about seven million Buddhists outside of Asia,46 Buddhist temporality would likely present an unfamiliar framework for these audiences. The dearth of consideration of Buddhist temporality in both popular and scholarly discourses on Weerasethakul, who has stated that he follows a Buddhist “way of life,”47 further suggests that this meaningful cultural difference is being overlooked.

One primary tenet of Buddhist philosophy is the rejection of time as an independent reality. Among the plentitude of Buddhist schools of thought, there is consensus that “[t]ime as a substratum… – pastness, presentness, and futurity – is a pure and simple imagination without any phenomenal or objective ground.”48 As opposed to Christian temporality, which linearly progresses from divine creation to the telos of Judgment Day, or Judaic temporality, which awaits the ultimate salvation of a Messiah’s return, Buddhism contends that reality is ontologically dynamic and that everything in existence is impermanent and transitory.49

One technique Buddhists use to explore this impermanence is an analytical sitting meditation, vipassanā, that “encourages moment-to-moment mindfulness of the inconstancy of events as they are directly experienced in the present”50 and in many ways, approximates the experience of watching a Weerasethakul film. Similar to a vipassanā session, the director’s long takes focus viewers and hone their attention on seemingly minor details. The recurrence of natural landscapes and urban development in the long takes provoke comparable revelations of the material world’s transience as well. The meditative gaze is more explicitly invoked when characters like Dr. Nant in Syndromes, Boonsong in Uncle Boonmee, and the soldier and tiger spirit in Tropical Malady stare fixedly into the camera. This Brechtian dismantling of the fourth wall is partially a strategy to push viewers into considering their own inconstancy. Like vipassanā, it can lead to the deconstruction of binary thought, turning away from closed-minded selfhood, and promoting an awareness of the concatenation of every life form.51

Weerasethakul’s works further reflect Buddhist temporality in their use of cyclicality. As Kapila Malik Vasaytan points out, Eurocentric analyses of film often overlook that over two millennia of artistic practices in South and South East Asia are predicated on the belief that time is cyclical.52 Indeed, themes of recurrence and regeneration course through the history of Asian cinema, including in films like Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring (Ki-duk Kim, 2003), Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu, 1953), and The Apu Trilogy (Satyajit Ray, 1955-1959).

In Uncle Boonmee, the titular character speaks about the karmic toll of killing insects and Communists and calmly accepts the presence of supernatural beings, but the notion of cyclicality also appears aesthetically. For instance, Boonmee dies in the cave where he was born. After entering the cave through a vaginally shaped aperture, he wanders the primordial, womb-like space before dying there, linking his beginning and end. In his final moments, the camera focuses on the moon and the trees above him, two other symbols that evoke samsāra, the perpetual Buddhist life cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. Like the dual sets of Roong, Jen, and Tong that close the film, this looping propels viewers to reassess the narrative more openly, now seeing every visualized moment twinned as both potential commencement and conclusion.

Blissfully Yours also employs a cyclical structure to subvert chronological expectations. Two of its opening scenes are set in a doctor’s office and a factory, signifiers of modernity, with the former denoting scientific progress and the latter suggesting industrialization and automatization. After demonstrating their frustrations with the material world, the characters abandon civilization in favor of a deserted, unspoiled forest. As the film progresses in clock-time, Min, Roong, Orn, and Tommy continue to detach from the putative advancements of urbanity. For instance, Min timidly removes his clothes upon first entering the forest, but after spending time there, the two pairs fully shed their social inhibitions and openly satisfy their sexual desires. To reflect this shift, the style of camerawork concurrently becomes more fluid and includes more hand-held follow shots of the couples.53

The regression to pre-modernity culminates when Min, Roong, Orn bathe together in a river, the water evoking another natural cycle and suggesting rebirth akin to the process of being “born again… of water and of the Spirit” that Christians ritualize through baptism.54 At one point, Orn submerges and stops her watch in the water, emblematizing the rejection of clock-time. The two women also cradle Min like a newborn, nursing him and peeling away his dead skin. The placement of his rebirth directly before the film’s conclusion signals the film’s evocation of cyclicity.

Orn submerging her watch

As a more overt provocation, the opening credits also abruptly appear forty-five minutes into Blissfully Yours, a choice that belies the prospect of temporal coherence and undercuts the reductive binary of beginning/end. Weerasethakul has observed that the credit sequence reflects the vulnerability and unpredictability of existence, stating, “It feels like life’s journey. We always change course. We may live one day and die the next. Films can change in the same way.”55

Intimately tied to cyclicality, Weerasethakul’s films also draw on the theme of reincarnation to uphold alterity and promote equal rights. In Uncle Boonmee, for example, the titular character neutrally comments that, in a previous life, “I don’t know if I was a human or an animal, a woman or a man.” This ontological destabilization, fitting the Deleuzian ideal of repetition with difference, is a vital constituent of Buddhist teachings. In Buddhist theology, rebirths attest that every being constitutes part of a mutual cycle of lives and indicate that each human “has been an animal, ghost, hell-being, and god in the past, and is likely to be so again at some time in the future.”56 The implication is that among the infinity of experiences that every individual comprises, everyone has at some moment experienced the same kind of suffering a particular being is undergoing currently.57 Therefore, those manifold parallels of experience demand not just compassion for but kinship with every form of life.

Weerasethakul further emphasizes indefiniteness by obfuscating Boonmee’s identity in both the visions of reincarnation and the present. He explains that Boonmee “could be every living thing in the film, the bugs, the bees, the soldier, the catfish and so on. He could even be his Monkey Ghost son and his ghost wife.”58 This is a radical assertion in several respects: the polymorphic uncertainty suddenly renders all creatures equally significant, while suggesting that the reputed protagonist may actually be playing an incidental role in the narrative at times and ceding the focus to unnamed beings. However, the most provocative idea it conveys is that Boonmee could temporally coexist with other manifestations of himself such as Huay and Boonsong, a delinearizing redesign of time that exceeds Buddhist beliefs and again accentuates every life form’s profoundly reflexive and interdependent nature.

By establishing an eternal continuum, reincarnation also underscores how stigmatized differences of race, gender, age, and sexuality become relativized and infinitesimal in the grander temporal scope. For example, in Tropical Malady, Tong informs Keng, “In my past life, I may have had ten wives,” as a long shot of the characters’ backs obscures their identities and their overlapping bodies suggest a single being. While Tong’s statement may signal his sublimated shame toward his current homosexuality, it also affirms how impermanent divisive social constructs are in the Buddhist worldview.

The reminder that all things are conditional can be further interpreted as a call to activism, an opportunity to challenge a historical moment’s restrictive status quos. This principle arose in the religion’s incipient stages when Gautama Buddha repudiated the rigidly hierarchical caste system of India and resonates through the modern age, as monks have opposed the Vietnam War, the occupation of Tibet,59 and the repressive governments of Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and China.60 Considered by many teachers an extension of the mindful service and acts of virtue the philosophy valorizes in dharma, social action can be an integral part of Buddhist observance, “combining this inner and outer work into a single seamless lifestyle, where activism is practice and practice is activism.”61 By advocating a circular view of history, Buddhist thought likewise exposes the falsity of economic and political stratification. It reminds us that the privileged and oppressive will interminably switch places with the disadvantaged and oppressed throughout the continuum of time.

As a unit, Weerasethakul’s oeuvre also displays intertexual properties of cyclicality and reincarnation, again enabling the director to showcase the value of difference. Many elements thread transfilmically, including themes like memory, militarism, and transformation; settings like jungles, caves, hospitals, and offices; and stylistic signatures such as tracking shots through car windows, intradiegetic performances of Thai pop songs, and allusions to the popular genres of the director’s childhood. These reiterations, contributing to a greater whole that Julia Kristeva describes as a “mosaic of quotations,” build upon previous referents in a process akin to the accumulation of karma.62 The recognition of how these intricate correlations interweave also requires multiple engaged viewings like the process of samsāra. Yet, because the elements are never repeated in exactly the same way, their distinctions demand as much attention as their commonalities.

In addition, actors Sakda Kaewbuadee and Jenjira Pongpas reappear in new roles in various films, another choice that parallels the notion of life cycles. As Keith A. Reader elucidates, “The very concept of a film star is an intertextual one, relying as it does on correspondences of similarity and difference from one film to the next, and sometimes too on supposed resemblances between on- and off-screen personae.”63 For example, Kaewbuadee plays Tong in Tropical Malady and Uncle Boonmee, as well as a tiger spirit in Tropical Malady and a monk named Sakda in Syndromes. That his character in Syndromes shares the actor’s name erodes the already frayed division between fiction and reality. The fact that Tong becomes a monk like Sakda, and like Weerasethakul and Kaewbuadee themselves once did,64 also suggests that their narratives and biographies are overlapping. Weerasethakul has even suggested that, despite the nominal difference, Tong and Sakda are the same character existing in a “multi-verse” world, and states that the 2010 scenes may be analeptic to the 2006 scenes.65 Thus, by repeatedly using the same actor, Weerasethakul not only ungrounds the constancy of identities, but creates delinearizing polychronies that span across films.

Weerasethakul similarly uses Jenjira Pongpas’ presence in Iron Pussy to illustrate the impermanence of selfhood. In a scene where the villain Tang is interrogating her character, the head maid Somjintana, Tang insists, “You are not just a maid. Tell me now who you really are.” On one level, these lines fit the generic demands of a cinematic interrogation scene, but the character is also metadiscursively referencing the intertextual connotations of Pongpas’ other roles. After unmasking her, Tang discovers that Somjintana, ostensibly a middle-aged woman, is actually his girlfriend Rungranee working undercover for the Special Forces Unit. Reinforcing his temporal rigidity, Tang contends that her transformation is logically impossible, because the much younger Rungranee could not have completed the twenty-five years of training that the Special Forces require. By removing two decades of aging, Tang’s action compels viewers to challenge the fixity of identities and reconsider the authenticity of every other character’s outward appearance.

|  |

Rungnaree’s face revealed under the mask

Moreover, Rungranee’s warning as Somjintana, “Under my pretty face lies another beautiful lady,” reveals that, like the film’s titular transvestite heroine, all individuals perpetually perform a myriad of visible and invisible roles that seep into each other. It also casts retroactive doubt on Pongpas’ incarnations as Orn in Blissfully Yours, Pa Jane in Syndromes, and the eponymous Jenjira in Uncle Boonmee, and the multitude of unseen personae the actress may be concealing in those manifestations.

The numerous instances of transfilmic characters ‘reborn’ in other settings, including Tong’s recollection of an uncle who can recall his past lives in Tropical Malady, Orn seeking a soldier named Keng in Blissfully Yours, and Roong’s return in the closing scene of Uncle Boonmee also disarray their current temporalities through their past associations. One such complicating rebirth occurs in Weerasethakul’s first two films, Mysterious Object and Blissfully Yours. In the former film, the real-life storytellers in the documentary use the fictional characters Dogfahr and her father as the basis for their tales, whereas in the latter film, Dogfahr and her father materialize within the narrative. Situated only eleven minutes into Blissfully Yours, their reincarnation underscores the illusory nature of the diegetic reality and accentuates the mediated processes of filmmaking. Thus, viewers familiar with Mysterious Object, in which the storytellers spatially and temporally shift these characters, must question the spatiotemporal properties of the latter film almost immediately. Yet, as longtime aficionados of Weerasethakul know, such displays of the imaginative, aberrant, and exceptional are ultimately normal in this life-world, interweaving throughout Blissfully Yours and the entirety of the director’s oeuvre.

ConclusionThroughout his career, Weerasethakul has endeavored to heuristically nudge viewers out of hegemonic logics and discriminatory social orders. As I have argued in this article, he frequently accomplishes this objective by synthesizing formal experimentation and the influences of multiple alternative identity temporalities. By highlighting and surpassing the putative limits of narrative convention, he aims to challenge the restrictively linear thinking of his countrymen, his government, and, as his films continue to gain international acclaim, cultures around the world.

In 2010, Weerasethakul stated, “Cinema is man’s way of creating alternate universes, other lives,”66 which evokes his desire to induce perceptual changes not only in his characters but in viewers as well. Indeed, his filmography contains many evocative representations of difference that encourage new ways of conceptualizing freer, more equitable societies. By reflecting thoughtfully variant relationships to time, his cinematic multi-verse proves to be singular and timeless but also interrelational and a product of its time—much like the medium of cinema itself.

NOTES

- Apichatpong Weerasethakul, ed. James Quandt (Vienna: Österreichisches Filmmuseum, 2009).

- Ji-Hoon Kim, “Between Auditorium and Gallery: Perception in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Films and Installations,” Global Art Cinema: New Theories and Histories, eds. Rosalind Galt and Karl Schoonover (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010) 125-141.

- In this article, I limit my corpus to Weerasethakul’s first six feature films, because his most recent films, Mekong Hotel (2012) and Cemetery of Splendor (2015), have not yet received distribution in the US as of this writing. While it would also be worthwhile to consider the variant temporal challenges Weerasethakul’s numerous short films or multimedia installations present, I lack the space to do so here.

- Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, trans. Jane E. Lewin (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983), 35.

- Ibid., 40.

- Apichatpong Weerasethakul, “Interview: Apichatpong Weerasethakul,” interview by Sam Adams, AV Club, 3 Mar. 2011 (Accessed 15 Jan. 2015).

- A Surrealist exercise originating in the 1920s, le cadavre exquis was itself a form of regressive time travel. André Breton explains, “When the conversation—on the day’s events or proposals of amusing or scandalous intervention in the life of the times—began to pall, we would turn to… childhood games, for which we were rediscovering the old enthusiasm.” Comparable to Weerasethakul’s projects, it aimed to liberate the imagination. See: Andre Breton, “Le Cadavre Exquis: Son Exaltation” catalogue (Paris, France: Galerie Nina Dausset, 1948), 5-11.

- David Herman, Story Logic: Problems and Possibilities of Narrative (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 219.

- Ji-Hoon Kim, “Between Auditorium and Gallery,” 132.

- Ibid., 136.

- All unattributed quotations, such as this one, come directly from the films they reference.

- Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 133.

- Genette, Narrative Discourse, 48.

- Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International, trans. Peggy Kamuf. (New York: Routledge, 1994), 6.

- Ibid., 6-7.

- Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), 68.

- Ibid., 69.

- David Bordwell’s estimate in James Quandt, “Resistant to Bliss: Describing Apichatpong,” Apichatpong Weerasethakul, ed. James Quandt (Vienna: Österreichisches Filmmuseum, 2009), 13-100, 50.

- Brian Henderson, “Tense, Mood, and Voice in Film (Notes after Genette),” Film Quarterly 36.4 (1983): 4-17, 10.

- Apichtapong Weerasethakul, “Interview: Apichatpong Weerasethakul on ‘Uncle Boonme’ [sic], Steven Spielberg, ‘Inception’ & More,” interview by Christopher Bell, indieWIRE’s The Playlist, 4 Mar. 2011 (Accessed 15 Jan. 2015).

- Deleuze, Cinema 2, 22.

- Ibid., 127.

- Marcia Landy, “Frames or Frame Ups of National Cinema?” KinoKultura, 29 Oct. 2004. (Accessed 20 Nov. 2011).

- Deleuze, Cinema 2, 125.

- This section is excerpted from The Primitive, a video installation that recalls the repressed memories of political violence in Nabua, a northeastern Thai village. Weerasethakul has stated that he presented this installation in a “nonlinear and nonchronological” fashion so that “the viewer can relate one video to another without any predetermined direction” (See: Apichatpong Weerasethakul, “Learning About Time: An Interview with Apichatpong Weerasethakul,” interview by Ji-Hoon Kim, Film Quarterly 64.4 (2011): 48-52). Notably, Boonmee’s dream adapts a dream that Weerasethakul once had, which creates additional synchronies of past and present and virtual and actual.

- Mary Ann Doane, The Emergence of Cinematic Time (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 209.

- Thierry de Duve quoted in Doane, 209.

- Walter Benjamin quoted in Doane, 209.

- Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit, A History of Thailand (Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 229.

- Ibid., 183.

- Sally Chivers and Nicole Markotić, “Introduction,” The Problem Body, eds. Sally Chivers and Nicole Markotić (Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 2010) 1-21, 10.

- Ben Bahan, “Face-to-Face Tradition in the American Deaf Community: Dynamics of the Teller, the Tale, and the Audience,” Signing the Body Poetics: Essays on American Sign Language Literature, eds. H-Dirksen L. Bauman, Jennifer L. Nelson, and Heidi M. Rose (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006), 21-50, 27.

- Edward Klima and Ursula Belluggi, The Signs of Language (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979), 192, 194.

- Petra Küppers, Disability and Contemporary Performance: Bodies on Edge (New York: Routledge, 2003), 27.

- Susan Wendell quoted in Küppers, 27.

- Simon Montlake, “Making The Cut,” Time, 11 Oct. 2007 (Accessed 15 Jan. 2015).

- Diana Fuss, “Introduction,” Inside/out: Lesbian theories, gay theories, ed. Diana Fuss (New York: Routledge, 1991), 1-10, 4.

- Jack (fka Judith) Halberstam, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 3.

- Ibid.

- Peter A. Jackson and Gerard Sullivan, “A Panoply of Roles: Sexual and Gender Diversity in Thailand.” Lady Boys, Tom Boys, Rent Boys: Male and Female Homosexualities in Contemporary Thailand, eds. Peter A. Jackson and Gerard Sullivan (Binghamton, NY: The Haworth Press, 1999), 1-27, 4.

- With discussions of transgender rights permeating mainstream discourse in the U.S. and the diversification of transgender representations and roles for transgender actors in film and television, the trope of the tragic transgender has thankfully declined in recent years.

- Han ten Brummelhuis, “Transformations of Transgender: The Case of the Thai Kathoey,” Lady Boys, Tom Boys, Rent Boys, 121-139, 126.

- Jaime Alfredo Cabrera, “Are You Man Enough to be a Woman?” Bangkok Post, 18 Jan. 2009.

- Peter Harvey, An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics: Foundations, Values, and Issues (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 5.

- “Monks on the March,” The Economist, 3 May 2007 (Accessed 15 Jan. 2015).

- Harvey, An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics, 5.

- Weerasethakul, “Learning About Time,” 52.

- Hari Shankar Prasad, “Time in Buddhism and Leibniz: An Intercultural Perspective,” Time and Temporality in Intercultural Perspective, eds. Douwe Tiemersma and Henk Oosterling (Amsterdam: Rodopi B.V., 1996), 53-63, 53.

- Ibid., 55.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Noble Strategy: Essays on the Buddhist Path (Valley Center, CA: Metta Forest Monastery, 1999), 33.

- Ibid., 37.

- Kapila Malik Vasaytan quoted in Roy Armes, Third World Film Making and the West (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1987), 135.

- Quandt, “Resistant to Bliss,” 50.

- John 3.3–3.5, AV.

- Quandt, “Resistant to Bliss,” 50.

- Harvey, An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics, 38.

- Ibid.

- Apichatpong Weerasethakul, “Interview: Apichatpong Weerasethakul on Uncle Boonmee,” interview by Serge van Duijnhoven, Film Juice, 24 May 2010 (Accessed 15 Jan. 2015).

- Sallie B. King, Socially Engaged Buddhism (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009), 21, 78, 68.

- Andrew Higgins, “How Buddhism Became Force For Political Activism,” Wall Street Journal, 10 Nov. 2007, A1.

- Ken Jones, The New Social Face of Buddhism: A Call to Action (Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications, 2003), 222.

- Julia Kristeva, Desire and Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art, trans. Thomas Gora (New York: Columbia University Press, 1980), 66.

- Keith A. Reader, “Literature/cinema/television: intertextuality in Jean Renoir’s Le Testament du docteur Cordelier,” Intertextuality: Theories and Practices, eds. Michael Worton and Judith Still (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1990), 176-189, 176.

- “Uncle Boonmee Crew/Cast,” Kick the Machine, n.d. (Accessed 15 Jan. 2015).

- Apichatpong Weerasethakul, “NYFF Interview: Apichatpong Weerasethakul,” interview by Peter Labuza, Labuza Movies, 28 Sept. 2010 (Accessed 15 Jan. 2015).

- Weerasethakul, “Interview: Apichatpong Weerasethakul on Uncle Boonmee.”

Time and Time Again: The Cinematic Temporalities of Apichatpong Weerasethakul by Daniel Grinberg is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License