Transnational Adaptation: The Complex Irreverence of Narrative Strategy in Nina Paley’s Sita Sings the Blues

By Tarini Sridharan

Nina Paley’s Web-based animated feature Sita Sings the Blues (2008) has occupied a remarkably unique position, poised between the lavish praise it continually earns, and subject to the censure it simultaneously provokes. Critics have raved over Paley’s genius, calling her a “one woman Disney.” The animated satirical documentary has now accumulated over thirty awards and honors for its visual beauty. It has functioned controversially; some critique it for being too “rarified” to be emotionally accessible to children while Hindu fundamentalists have attempted to have it banned in India. Copyright mavens took issue with Paley for bravely trying to appropriate the ancient Indian religious-mythological text, the Ramayana.

This article aims to highlight how the narrative technique of Sita Sings the Blues, as an adaptation of the classic Indian epic, functions subversively. The narrative strategy of the film is poised to constantly produce double-sided meanings, evoked through transnational collage. Such collage consists of multiple voiceovers, parallel narratives and disparate aural and visual threads. The unique ways in which these threads function lie in Paley’s employment of a narrative strategy that involves deliberate incoherence.

The film ‘speaks’ suggestively through its stuttered gaps in narrative, through its pauses and asides, as well as through its self-consciously doubtful narrative. Moreover, the multiple storytelling devices in the film complicate the notion of a singular ‘voice’ or ‘message.’ Satirical adaptations like Sita Sings the Blues (hereafter SSTB) destabilize the notion of looking at the world through static, singular frames of reference. Despite being a product of US culture, the effects produced by SSTB’s unique storytelling technique does not allow itself (or its audiences) to stay neatly and complacently within the bounds of a single national or cultural ideology.

Moreover, the film’s multiple disparate aural and visual registers introduce a strategic incoherence that destabilize centuries-old cultural texts. Paley’s film thus serves as a subversive feminist polemic. In order to examine how these narrative tactics function, it is necessary to first briefly introduce the background of the film, and then contextualize the Ramayana as a deeply entrenched patriarchal text.

Sita Sings the Blues is an eighty-two-minute feature written, directed, animated and distributed entirely by Nina Paley, an independent Jewish film-maker from Urbana, Illinois. In Paley’s film, the ancient Hindu epic The Ramayana is retold through the songs of a 1920s American jazz singer, Annette Hanshaw. Paley suffered numerous attacks and controversies over this film, most of them concerning copyright entanglements and censorship concerns. She originally conceived the idea when reeling from the heartbreak of a failed marriage. Her ex-husband had announced his intention to leave in an email when she was away on a business trip, and she transformed her pain into art by creating SSTB. Two cultural sources helped her through her heartbreak: the ancient Hindu text The Ramayana, and the songs of American singer Annette Hanshaw. Through the prism of her own lived experience, she detected parallels between Hanshaw’s poignant love songs and the plight of one of the Ramayana's central characters, Sita.

The story of Sita, central to the Indian epic poem, is counted among the world’s most widespread classics. There are more than seventeen major Ramayanas that have been adapted from the original text by Valmiki in various Indian and Southeast Asian languages. The text snowballed from its oral ballad traditions and almost any Indian is familiar with its story. So pervasive is the Sita story that the nation would practically come to a halt every Sunday morning when the Ramayana program (produced and directed by Ramanand Sagar) was telecast in the late 1980s.

Sita is an elemental mythic figure, born emerging from a crack in the earth, who accompanies her husband Prince Rama in his fourteen-year exile to the forest, where she is kidnapped by the demon king Ravana. This sets off a series of fierce epic battles until Rama finally rescues her, but instead of a happy reunion, he rejects her because he doubts her fidelity. As required, Sita throws herself into a blazing fire to prove her purity. Her innocence is confirmed when she emerges unscathed from the flames, but this does not satisfy Rama. As rumors persist in the countryside, bowing to public opinion, he banishes Sita to the forest without warning, even though she is pregnant with his two sons. Sita gives birth to twins alone in the forest and raises them by herself with the help of the sage Valmiki. Rama later reclaims his sons but suggests a second fire ordeal for Sita. At this point Sita calls upon her mother, the Earth, to receive her once again, and the ground parts beneath her feet and Sita ‘returns’ to the Earth, from where she first emerged. She is a classic figure of tragic mythic femininity.

The cultural hegemony of the Ramayana is ever-present in India. Lakshmi Lal in Myth and Me: The Indian Story highlights the unique ways that mythology functions in India: ‘In Western cultures the whole concept [of myth] has been devalued along with the word. A myth is something to be exploded. The Indian tradition advises us to pay serious attention to a myth, reflect upon it, make it part of our lives…the Indian is myth-born and myth-fed.”1 Psychoanalyst Sudhir Kakar2 describes the “intimate familiarity” of this ancient fable to Indians thus: ‘From earliest childhood, a Hindu has heard Sita's legend recounted … heard her qualities extolled in devotional songs; and absorbed the ideal feminine identity she incorporates’ (1988:53)

How does Paley’s film evoke a transnational subversion of Sita’s mythic femininity through its narrative strategy? The “transnational” scope of SSTB weaves together disparate cultural references across time-space. The tongue-in-cheek title Sita Sings the Blues is emblematic of precisely such contradiction. Sita, a passive mythical figure from ancient India, actively “sings the blues.” The title is a juxtaposition of fragmented cultural references, a contradiction in terms, suggestive of the film’s agenda. The reference to 21st century Americana (the “blues”) evokes a geographical and temporal leap. It plucks Sita out of mythic immobility, allowing her to function dynamically and subversively.

The fragmented, splintered and multiple narrative devices of SSTB not only de-familiarize the familiar but also destabilize the flatness of mythic hegemony, transforming and imbuing it with new, subversive meanings. SSTB turns the unquestioned flatness of mythic simplicity on its head, lending it a complicating depth and contour. Such transformation is aided by the disparate transnational elements it presents. SSTB juggles diverse forms of artistic representation and tradition. It presents these via different narrative voices that span temporally and spatially disparate moments in a variety of animation styles and narrative tonalities.

It is worthwhile to reflect on the significance between image and language in SSTB. Both are modes of expression linked together in ideologically complex ways. W.J.T. Mitchell highlights what Foucault calls ‘the infinite relation of language to painting.’ He reasons: ‘this fault line in representation is deeply linked with fundamental ideological divisions. The differences between images and language are not merely formal…they are in practice linked to things like the difference between the (speaking) self and the (seen) other; between telling and showing; between ‘hearsay’ and eyewitness testimony; between words (heard, quoted, inscribed) and objects or actions (seen, depicted, described); between sensory channels, traditions of representation and modes of experience.”3 (emphasis mine). Where does SSTB enter into this discourse? The earliest indication comes from the film’s opening scene.

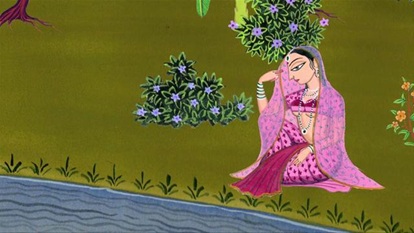

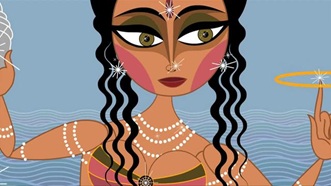

Fig. 1

We see Sita in the form of the goddess Lakshmi, who rose from the waters when the seas were created. She is presented in the mode of an exotic-erotic woman, a mythic goddess embodying qualities of Oriental inaccessibility (she appears mute and, for a while, unblinking.) Next to her is a peacock, balanced on a gramophone record player, complete with snake-shaped legs. The graphic design corresponds to classical Indian mythic typology, yet a curious subversion is taking shape. In a minute, the gramophone begins to play to the tune of the 1920s jazz vocalist Annette Hanshaw’s appropriately titled song “Mean to Me”. Sita, although mute, enthusiastically sways in enjoyment until the record stops, looping over the line ‘a woman like me’:

‘Moaning low,

My sweet man I love him so,

Though he’s mean as can be

He’s the kinda man needs

A kinda woman like me,

A woman like me, a woman like me, a woman like me’

As this is our first introduction to Sita, it begs the question – whose story are we being introduced to? Sandra Annett has pointed out that the gramophone recording interferes with the idea of “natural” performance. To take this view further, I argue that it also complicates our conception of “natural” femininity. The disruptive looping of the line “a woman like me”, as Annett has pointed out, prompts us to ask: a woman like whom exactly? A Hindu goddess? An American jazz singer? Paley herself? Who and what are these women like, exactly? And whose subjectivity – whose voice – are we being introduced to? Alluding to Judith Butler’s analysis of Aretha Franklin’s song “(You Make Me Feel) like a Natural Woman”, Annett highlights that “woman” is defined by the simile “like,” revealing the constructed, performative aspects of gender.4 Such an opening subverts mythic simplicity on an imagistic level. There is, arguably, no image more iconoclastically representative of essentialized femininity than a ‘natural’, elemental woman rising from the waves. Lal describes such imagery evocatively: ‘Lakshmi bursts upon the world in all her golden glory thrown up by the mythical churning ocean of milk, borne aloft on Creation’s lotus.”5

Fig. 2

This image of Indian mythic femininity, so iconoclastic and emphatic, is faithfully introduced in the opening of SSTB and immediately destabilized. Sita’s exaggeratedly exotic, oriental appearance works to subvert such tropes. She is presented as so hyperbolically mythic, so excessively feminine, that she appears mildly comical. As a portrait of mythic femininity, it is both self-mocking and self-reflexive. To quote Sandra Annett: “Rather than simply Americanizing the Ramayana, (Paley) deliberately plays through exotic and erotic imagery. This creates what Graeme Huggan, riffing on Spivak's ‘Strategic Essentialism’ calls ‘strategic exoticism’ in which postcolonial writers/thinkers, working from within exoticist codes of representation, either manage to subvert those codes or succeed in redeploying them for the purposes of uncovering differential relations of power."6 (emphasis mine)

Paley’s film unfolds in two parallel narratives across culturally and temporally disparate time zones. The first narrative follows the trajectory of Sita in a retelling of the Ramayana through Indonesian/Indian shadow puppets, functioning similar to a Greek chorus. The mythic fable is articulated from the vantage point of Sita (whose perspective often is ignored in the patriarchal framework of the original text.) Visually, this narrative thread is presented through multiple artistic renditions of Sita. Her different visual avatars suggest a modernist splintering of identity, as Paley faithfully draws from a multiplicity of visual renditions of the goddess in Indian art. She also presents an Americanized version of Sita, who bears a distinct resemblance to the sexy American cartoon figure Betty Boop, as seen in Fig. 5.

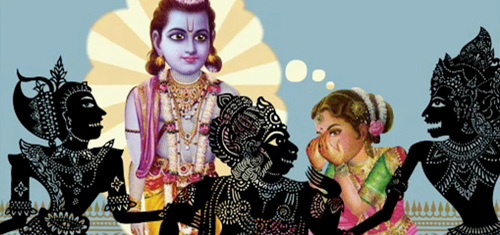

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

As Annett highlights, ‘Paley uses a range of visual styles to tell this multilayered narrative, from 'traditional Rajasthani miniature painting' to classic American graphic design, each corresponding to a different narrative thread.”7 The visual allusion to Betty Boop is enhanced by the fact that each time Sita appears in this style, she “sings” an American jazz number by Annette Hanshaw, evoking Boop’s sassy, jazzy persona.8 The overall effect is a juxtaposition of temporally and spatially discrepant images across cultures and time-space. This retelling of the mythical tale is lent irony and subversion as narrated by a troupe of three irreverent shadow puppets, who appear to strike a hybrid mix between Indian and Indonesian shadow puppets. Paley stated that while she used Balinese shadow puppets, they were also a hybrid of many South Asian (and Indian) traditions. They function as narrators/commentators (two of them male, one of them female), who discuss and narrate the Ramayana in light of Sita’s role. They provide an ironic contemporary viewpoint on the historical significance and contemporary relevance of the Sita story, providing multiple readings of the Ramayana. When they talk amongst themselves, they use phrases like “basically,” ”actually,” and ”you know” rather than precise language or exact references. In addition, these shadow puppets speak in educated, contemporary Indian voices, providing a contrast to their pictorialization as ancient storytellers. The puppets improvise their own irreverent explanation of the Ramayana.

Fig. 7

The voice actors in the film are Indian friends of Paley, and their lively dialogue simultaneously narrates and undermines the historical importance of the Ramayana. I argue that their employment in this film functions in the same way that the figure of the sutradhar does. The term has its roots in Indian theatrical traditions, where ‘sutradhar’ literally meant ‘thread holder’: a figure in Sanskrit theater who was the head of the troupe, analogous to a modern director or stage manager. But the term can also suggest a metaphorical thread that holds a narrative together. The figure of the sutradhar in Indian tradition usually established a rapport with the audience—he announced and linked the action together. Thus, the sutradhar was central, yet kept his or her presence in the background. The term can also be broadened to encompass roles such as director, narrator, singer, reciter or commentator in theatrical traditions. Relevant to SSTB, the concept of the sutradhar actually originated in ancient Indian puppetry; in a very literal sense as the string puller. India has a rich tradition in shadow theater, and unlike puppet theater where the audience directly sees the puppets, shadow theater meant the audience could only see their moving shadows cast by light on a screen.

Fig. 8

The hybrid puppet figures make SSTB a multi-voiced manifesto. Their interpretations entail a retelling of the Ramayana that fluctuates according to historical periods, literary traditions, and even generic styles. To add to this, the film traverses geographically diverse spaces across the cities of San Francisco, New York and modern-day Trivandrum in India, taking the Sita myth well beyond its point of origin.

The selection of the three individuals who voice Paley’s puppet narrators are far from random. The voice actors in the film come from media backgrounds, and their voices represent a liberal, educated Indian upper class sensibility. Aseem Chhabra is a freelance writer and columnist for the Mumbai Mirror; he is also programmer for the New York Indian Film Festival, Bhavna Nagulapally is an actress, Manish Acharya a filmmaker and actor. All three give voice to the shadow puppets, who at times playfully evoke gender warfare (the female puppet often disagrees with the verdict of the two male puppets). What is apparent is that the voice actors are accustomed to articulating themselves in film, media or print. They are voices of urbane, well-traveled Indians, all Hindus by background, clearly familiar with the Ramayana, and aware of what Paley expects them to do. They aim to be entertaining, genial, funny, satirical and occasionally censorious, but always detached, ironic and sophisticatedly tolerant. At one point the female narrator exclaims in a tongue-in-cheek aside: "You can't question that. That’s blasphemy!”

Fig. 9

In a reversal of traditional omnipotent narrations of the epic, the shadow puppets speak in ironic, confused sentences, lending a questioning, critical tone to the narration. This serves to locate the Ramayana between history and myth, between fact and fiction. Even their asides and mispronunciations are deliberately self-reflexive. The opening narrative sequence establishes not just the tonal identity of the puppets but also their inexactitudes and the dynamic interplay of their observations, opinions and descriptions. Since it is the opening sequence, they are required to contextualize the Ramayana in terms of its time, place and authorship. Instead of a clear introduction, we hear a series of incoherent, confused sentences. Dates are mixed up, the number of wives of King Dasharatha are contested, until they eventually arrive at a commonly agreed verdict through interactive dialogue and banter, in what I see as a postmodern framing of the epic.

The visuals accompanying their dialogue illustrate their corrections and mistakes, animated as if their thoughts were being visually registered. This original technique, in the interplay between image and aural text, is one instance of how the film effects a destabilization of dominant ideological perspectives. Nina Paley has asserted that these narrations were completely unscripted and authentic. The narrative technique of SSTB effects a constantly deliberate, strategic incoherence. The first dialogue exchange between the puppets provides a sample of this as the Ramayana is first introduced:

Shadow Puppet 1: When?

Shadow Puppet 2: I don't remember what year...

Shadow Puppet 1: There's no year...

Shadow Puppet 2: How do you know there's a year for that?

Shadow Puppet 3: I think they say the 14th Century.

Shadow Puppet 1: The 14th Century was recently.

Shadow Puppet 2: No, but... I don't know...

Shadow Puppet 1: That's when... the Moghuls were ruling, Babar was in India…

Shadow Puppet 3: OK, the 11th then.

Shadow Puppet 1: It's definitely B.C.

Shadow Puppet 2: It's B.C. for sure.

Shadow Puppet 1: And I think it's Ayodhya, where Ram was born.

Shadow Puppet 2: I know that, because they razed that temple…

Shadow Puppet 1: They say that Ram was born there. Which I don't believe -

Shadow Puppet 2: - but that's what they say.

Shadow Puppet 3: And Ayodhya is in the state of Uttar Pradesh.

Shadow Puppet 1: It's right there! Therefore the story has to be true…

The second narrative in SSTB is an unfolding of Paley’s own autobiographical story. It recounts how she first moved to Kerala with her husband, only to be dumped by him via email when she went back to New York on a short business trip. Time in SSTB thus traverses two wholly different temporal modalities, the mythic and contemporary, the fictive and the real, yet time is neither “linear nor cyclical”; rather, different time frames are contextualized in a unified whole.9

Fig. 10

Paley’s animation style for depicting herself is much simpler, consisting of clear, economical outlines reminiscent of comic-book simplicity. In it, Paley animates herself and her lived experience. Fig. 10 shows Paley in San Francisco with her husband in a moment from the opening segment of the film. At this point, Paley and her husband are shown contentedly leading uneventful lives until Jeff receives a job offer requiring him to move to India.

Fig. 11

Once he moves, he is neglectful of Nina, forgetting to keep in touch with her. It is almost as if he has become infected with the ‘disease’ of patriarchy, a ‘disease’ seemingly inherent to the soil of this vast, foreign country. Paley’s heartbreak and confusion are interspersed with the tragic mythic narrative of Sita in her abandonment. Sita’s trial by fire eerily echoes with Paley’s own experience of heartbreak and rejection.

Fig. 12

This allows Paley to juxtapose her own story with the ancient Indian text, to use the figure of Sita to vicariously fictionalize her own grief in intimately subversive ways. She redeploys the mythic fable to feminist purposes, evoking a strong critique of the misogynistic undertones carefully contained in the religious text. It is no surprise, then, that this film was met with such heated protest by Hindu fundamentalists, who accused Paley of attacking their religion. Paley is attempting what no one has really dared attempt before in an animated adaptation: a feminist intervention of arguably one of the most patriarchal texts in India.

Sita, who Lal describes as “the very soul of unquestioning acceptance,”10 is a perennial symbol of this patriarchal universe, handed down for generations in Indian culture as the ‘Ideal Woman.’ Linda Hess, in her essay "Rejecting Sita: Indian Responses to the Ideal Man's Cruel Treatment of his Ideal Wife", discusses Sita’s humiliation: ‘Sita's raw deal is dramatized primarily in three episodes … First, the fire ordeal in which Sita must undergo a test of chastity that requires her to throw herself into a blazing fire. Second is the abandonment of Sita … Rama decides that despite her having passed the fire test … despite her being in an advanced state of pregnancy, Sita must be banished … The third moment of rejection [is when] Rama makes a final attempt to bring Sita back after she has lived for years in the forest, raising their sons to young manhood without him. He suggests that she endure one more fire ordeal.’11

Paley explicitly attacks such misogynistic tones in the lyrics to one of SSTB’s songs by satirically ‘praising’ Rama: “Perfect man, perfect son/ Rama's loved by everyone/ Always right, never wrong/ We praise Rama in this song/ Sing his love, sing his praise/ Rama set his wife ablaze/ Got her home, kicked her out/ To allay his people's doubt.” SSTB also illustrates Sita’s victimized position by constantly animating her entrapment. One of the most demonstrative examples of this is the pictorialization of Sita massaging Lord Vishnu’s feet on the Sesh Naga at the start of the film. The Sesh Naga is an avatar of the Supreme God, the King of all Nagas. It is said that when Sesha uncoils, time moves forward and creation takes place, and simultaneously when he recoils, the universe ceases to exist. “Shesha” in Sanskrit texts implies the “remainder” – that which remains when all else ceases to exist. It is an immensely patriarchal image, where male divinity figures literally as the centre of the universe. Sesha in this form is a manifestation of Lord Vishnu, another avatar for Rama.

Lal describes the Sesha Naga as following: “As Vishnu slumbers through interludes of recuperation, she is awake and on guard pressing the Lord’s feet, weary with treading the world’s thorny paths, reviving with her touch the myriad impulses that need to quicken in the Preserver’s being as he goes about his business of world management.”12

Fig. 13

How does SSTB topple this deeply patriarchal image? In what further ways does Paley’s film satirize and subvert such mythic tropes? Ipshita Chanda offers an interesting insight as she discerns similarities in the cartoon image of Vishnu (Fig. 13) to the American cartoon Johnny Bravo: ‘The voluptuous cartoon of Sita's counterpart is a bare blue-bodied Rama drawn to resemble the muscled Johnny Bravo, a cartoon character who is all man and putty in the hands of women … shifting to different styles of art within the same text for purposes of homage and/or parody.”13 She asserts, “[T]he cartoon style has a different purpose: exaggeration with a view to comic effect, as underlined by the stark resemblance between Johnny Bravo and Rama. This does not exhaust the possibilities of intermediality, however, for now we encounter a meeting across media boundaries … The visual text is a representation of a couple with exaggerated physical outlines [which] define and identify masculinity and femininity, Rama and Sita.”14

SSTB functions as a subversive text owing to the way its various narrative registers form a productive interplay between image, sound, text and ideology. To recall Mitchell, “the pictorial turn is not a return to naïve mimesis, copy or correspondence theories of representation, or a renewed metaphysics of pictorial presence: it is rather a post-linguistic, post-semiotic rediscovery of the picture as a complex interplay between visuality, apparatus, institutions, discourse, bodies, and figurality.”15 The conclusion of Paley’s film features herself, as a single woman, tucked into her bed at night with her cat Lexie, reading the Ramayana – an image suggestive of Woman taking Myth into her own hands (as the film is living proof of).

Fig. 14

Outside her window, in a starry nocturnal sky, Sita suddenly appears. She is seated on the Sesh Naga, only this time, in a complete reversal of patriarchal myth, it is Sita who reclines and balances the cosmos on her index finger, while the male god, Vishnu, is seen massaging her feet. There is a close up to her face: she looks directly at us, breaking the fourth wall, and winks.

NOTES

- Lakshmi Lal, Myth and Me: The Indian Story (New Delhi: Rupa, 2003), pp.x-xi.

- From Purnima Mankekar, Screening Culture, Viewing Politics (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1999), p.210.

- WJT Mitchell, Picture Theory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), p.5.

- Sandra Annett, “New Media beyond Neo-Imperialism: Betty Boop and Sita Sings the Blues”, Journal of Postcolonial Writing (Vol. 49 Issue 5, 2013), p.9.

- Lakshmi Lal, Myth and Me: The Indian Story (New Delhi: Rupa, 2003), p.83.

- Sandra Annett, “New Media beyond Neo-Imperialism: Betty Boop and Sita Sings the Blues”, Journal of Postcolonial Writing (Vol. 49 Issue 5, 2013), p.12.

- Sandra Annett, “New Media beyond Neo-Imperialism: Betty Boop and Sita Sings the Blues”, Journal of Postcolonial Writing (Vol. 49 Issue 5, 2013), p.8.

- Ibid.

- Ipshita Chanda, “An Intermedial Reading of Paley's Sita Sings the Blues”, CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture (13.3, 2011), p.6.

- Lakshmi Lal, Myth and Me: The Indian Story (New Delhi: Rupa, 2003), p.103.

- Linda Hess, “Rejecting Sita: Indian Responses to the Ideal Man's Cruel Treatment of his Ideal Wife”, Journal of the American Academy of Religion (67/1, 1999), p.3

- Lakshmi Lal, Myth and Me: The Indian Story (New Delhi: Rupa, 2003), p.81.

- Ipshita Chanda, “An Intermedial Reading of Paley's Sita Sings the Blues”, CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture (13.3, 2011), p.5.

- Ibid.

- WJT Mitchell, Picture Theory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), p.16.

Transnational Adaptation: The Complex Irreverence of Narrative Strategy in Nina Paley's "Sita Sings the Blues" by Tarini Sridharan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License