Playfully Subversive: the Many Roles of Adaptation in Making Games at the UCLA Game Lab

By David O’Grady

Introduction

The concept of adaptation—the process of change—is so associated with art and narrative practice for those of us in the humanities that its biological application recedes from view. Games, however, as rule-bound, organized forms of play, reside at the intersection of nature and nurture, of biology and culture. Because games are representations of both the material world and our agency within it, adaptation emerges as a central feature of game design—and game play. Said another way: games are born out of adaptation, they live in the adaptations of those who play them, and they perish when they no longer prove adaptable.

If games themselves reflect a complex life cycle of adaptation, the biological imperative to play them is equally adaptive. In Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Gregory Bateson formulated his now oft-quoted observation of dogs at play: “The playful nip denotes the bite, but does not denote that which would be denoted by the bite” (183). The nip, in other words, adapts—or quite literally, defangs—the bite’s function and meaning, commuting the dog’s mouth into a playful prop.

As recent animal studies suggest, the energy and risk expended in play far outstrips any practical or developmental benefit we may use to “explain” or “justify” the activity. Play, in other words, adapts, repurposes—subverts—the necessary, the serious, and the requisite in the pursuit of autotelic pleasure. As theorist Johan Huizinga notes in Homo Ludens, or “Man the Player,” play evinces the existence of personal agency independent of—and even oppositional to—nature and culture: “Play only becomes possible, thinkable and understandable when an influx of mind breaks down the absolute determinism of the cosmos” (3). Play, in short, is a subversive act.

For human players, games join the other arts as the mental instruments—the play spaces—for the subversion of cosmic determinism. As with any art form, games can dissipate or lose their subversive qualities, especially as game genres form and harden (e.g., the first-person shooter). But even the most banal game posits a “new,” adapted world built and stylized by the game designer; the player, in turn, may subvert this world to her own aims. Because games are often played with others, this subversion can take on a communal dimension. In online play of Grand Theft Auto IV, for example, players often drive their stolen cars to the game’s airport—not to slay each other wantonly (as encouraged by the game’s kill-or-be-killed ethos)—but rather to drag race on the lengthy runways; a honk of the horn and a rev of the engine signal the player’s competitive, but non-fatal, intentions. Subversive adaptations such as this are impossible to contain.

But they can be encouraged. Cultivating the subversive in game design and game play is perhaps the defining, unifying aesthetic of the games made at UCLA Game Lab. Founded and directed by artist Eddo Stern, a Design Media Arts (DMA) professor at UCLA, the lab fosters research and development in not only computer or video games, but also physical, tabletop, and other game forms. Known for its annual Game Art Festival at the Hammer Museum in Westwood, California, the lab supports the production and exhibition of student work, but it also curates and promotes vanguard game design from around the world. Through its tripartite mission to push the envelope of game aesthetics, game context, and game genres, the lab nurtures game projects that often adapt contentious, controversial subjects not found (overtly, anyway) in many commercial games: issues of politics, gender and identity, industry and commerce, the environment, experiences of alterity, the silly and the surreal…. In short, all that composes lived experience becomes fair game, so to speak, for adaptation.

To illustrate the diversity of adaptation challenges confronting the game designer, the rest of the article is devoted to showcasing a few recent and ongoing game projects in the lab. To learn more about UCLA Game Lab, and to check on the status of these games and many others, please visit the lab’s website at http://games.ucla.edu

Adapting other media: playing the “women’s magazine” ideal in Perfect Woman

Website: perfectwomangame.com

UCLA Game Lab visiting researchers Lea Schoenfelder and Peter Lu were inspired to create Perfect Woman from the ubiquitous personality questionnaires featured in women’s magazines and the female roles they define. Using the Microsoft Kinect motion-capture camera, players literally contort themselves to fit into the many roles and contexts in which women stereotypically are pressured to perform, such as family, career, sex, and so on. As Lu describes, “Perfect Woman uses these stereotypes as building blocks to critique social conventions, as well as to give you the chance to redefine what it means to be the perfect woman.”

The game embodies adaptation as both an interactive challenge—the better a player can match a contorted pose onscreen, the more “perfect” her rating level—and as an indictment of the impossible adaptations women are often expected to achieve. In terms of its birth-to-death structure and scope, Perfect Woman adapts an influential life simulation game, titled Alter Ego (1986), into a game of physical embodiment with in-game consequences: the game’s narrative reflects not only how well the player performs, but also what choices the player makes along the way. “What we do, and how well we do it, often determines success in life,” Lu said. “As our game illustrates, it’s not always possible to be perfect at every stage of life—and that’s perfectly fine.”

Making sport of the Sochi Olympics: Joe Wurzelbacher (Joe the Plumber): Defender of the American Dream

In a single game, Nick Crockett, a senior in DMA, manages to critique American, Soviet, and Olympic jingoism and homophobia by casting the player as Joe Wurzelbacher, better known as right-wing everyman Joe the Plumber, as a machine-gun toting Olympic snowboarder. The player’s goal is to slalom around giant pink phalluses to the bottom of the run, where the final, big-boss battle awaits with a giant-headed Vladimir Putin, as inspired by the character Andross in Nintendo’s Star Fox games.

For Crockett, games about politics represent a fusion of his interests, but their cartoonish style and iconography belie the real political criticism they contain. “Part of my motivation as a game designer is to respond to the real world in a satirical way—something that a lot of people have felt is a way to legitimate games as an art form,” Crockett said. “For me, the homophobia around the Sochi Olympics presented a complicated case, as our own history of discrimination in the U.S. doesn’t really give us the high moral ground. The game ended up being my personal response to the conflicted social and political response to the Olympic games.”

Crockett’s next game, a two-player boxing game for mobile devices with a twist—both players must stand toe-to-toe and hold onto the screen while playing—confronts a common challenge for designers: adapting games to their exhibition spaces. If the arcade space indelibly marked early video games as three-lives-for-a-quarter experiences, contemporary game designers grapple with designing games for gallery exhibition and other public areas where games are not only played but also watched by spectators. Crockett is planning to capture a ringside feel to the boxing game by connecting the players’ screen to a large-screen display—an approach akin to watching a pay-cable match on a bar’s giant TV.

A fish out of water in a classroom of dolphins: Classroom Aquatic

Website: http://classroomaquatic.com/Creative team: Eric Cappello, Adeline Ducker, Mickey Goese, Remy Karns, Heather Penn, Mikal Saltveit

Adapting game design to new interfaces also presents a creative challenge. The new virtual reality headset, Oculus Rift, offers the promise of true 3D immersion, but designing for that experience means confronting the technological limitations of the device—and its perceptual implications, such as the risk of motion sickness. In the game Classroom Aquatic, the player descends into the underwater world of a classroom of dolphins. Taking your seat at a student desk, your objective is to pass a written test on questions nearly impossible to answer, unless one “cheats” off other students by physically looking and leaning with the Oculus Rift headset. By confining the player to a desk underwater, the game successfully incorporates into game play the Oculus Rift’s relative immobility (it requires cables) and lag, which can give users a visually slurred, underwater feeling.

As the only human in the class—even the teacher is a professorial porpoise—one feels like and is meant to feel like a fish out of water. “It’s like you’re a foreign exchange student in an alien environment,” said Adeline Ducker, a graduate of DMA, one of the designers for Classroom Aquatic. “People who’ve played the game tell us it gives you the perfect sense of being in a culture that’s not yours. Dolphin teacher talks in dolphin, the students talk in dolphin… and everyone seems prepared for the exam except you. It creates a huge sense of anxiety.”

Mining the implications of globalization in rural Minnesota: The Iron Range

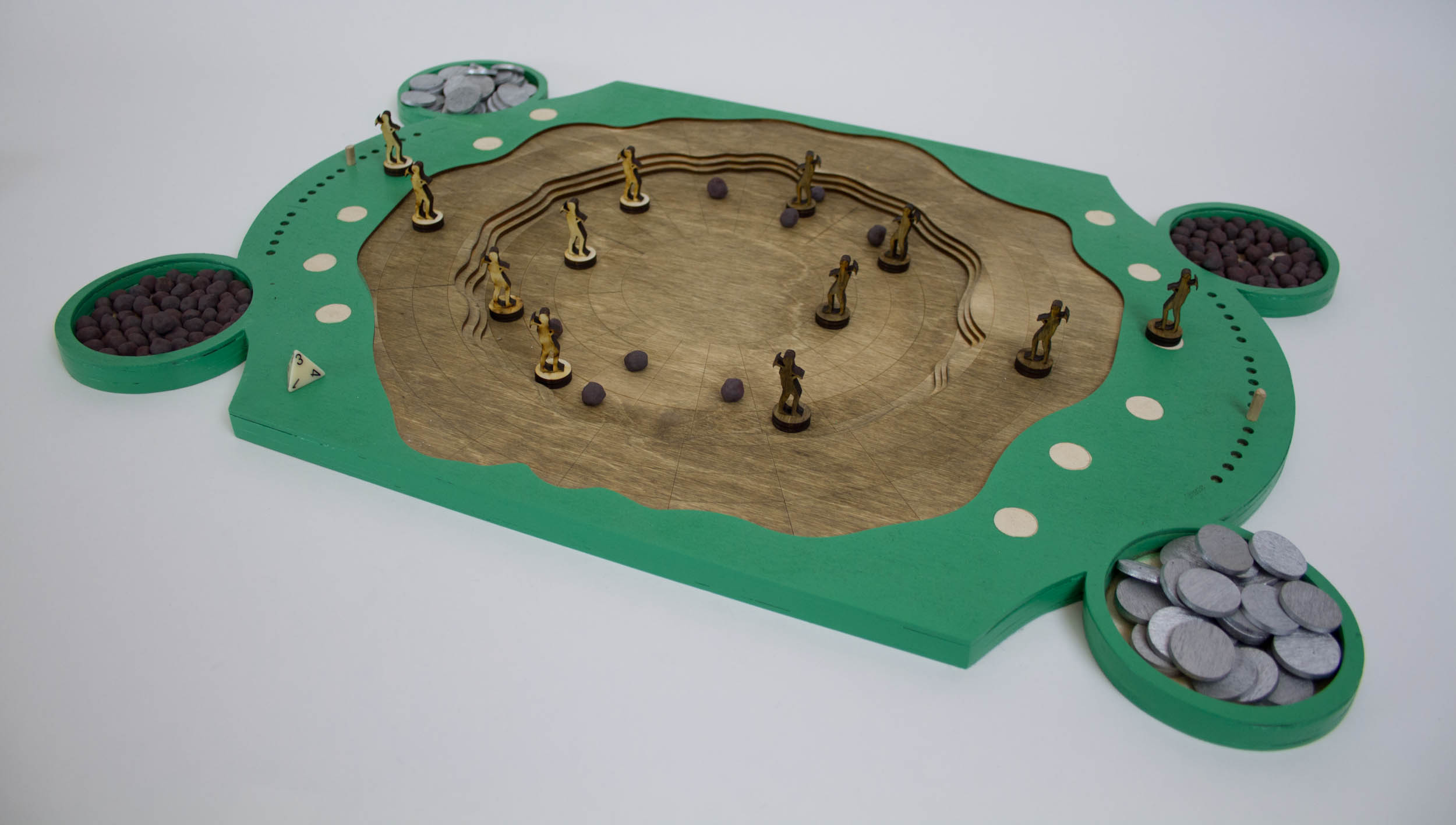

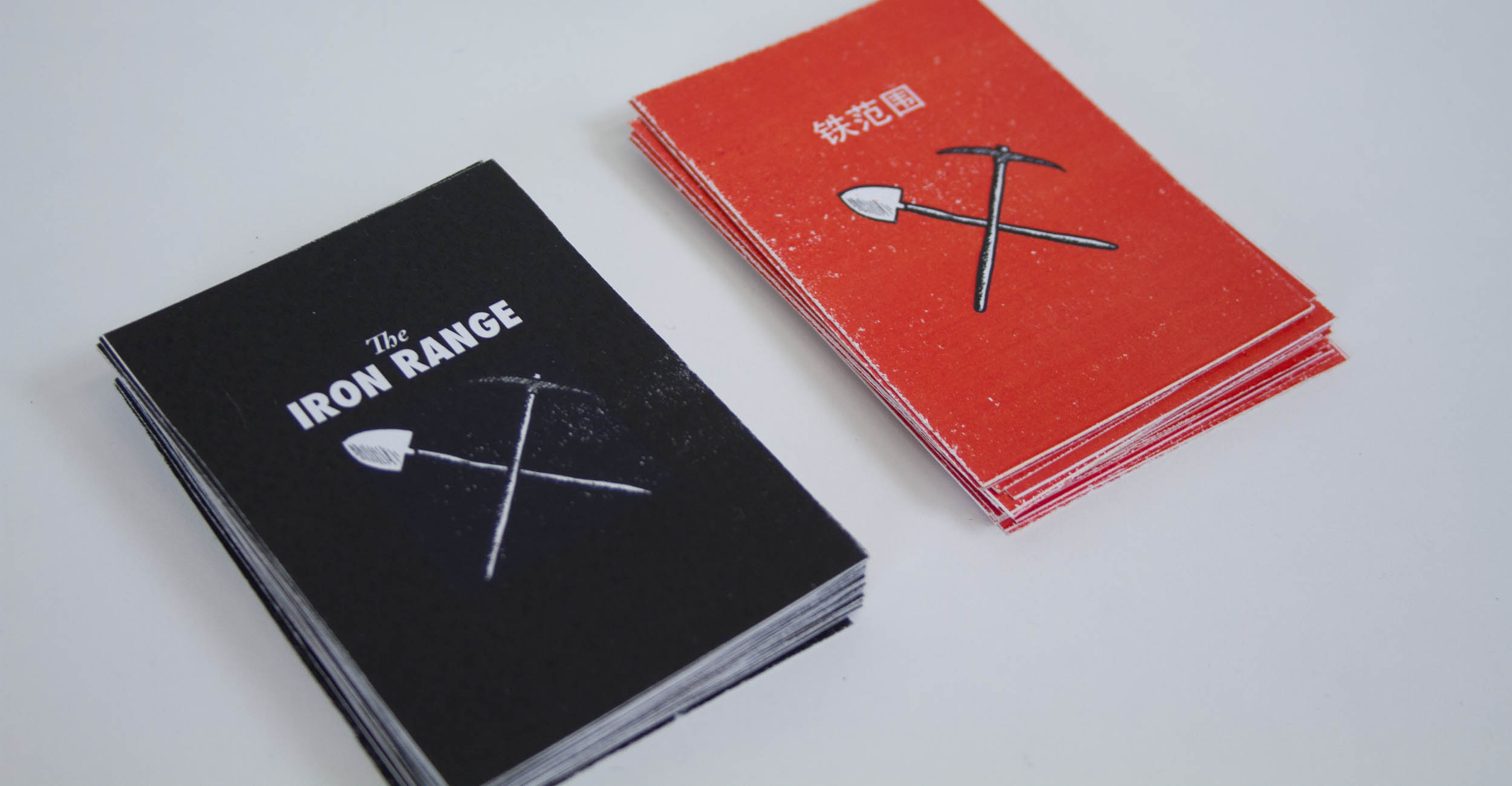

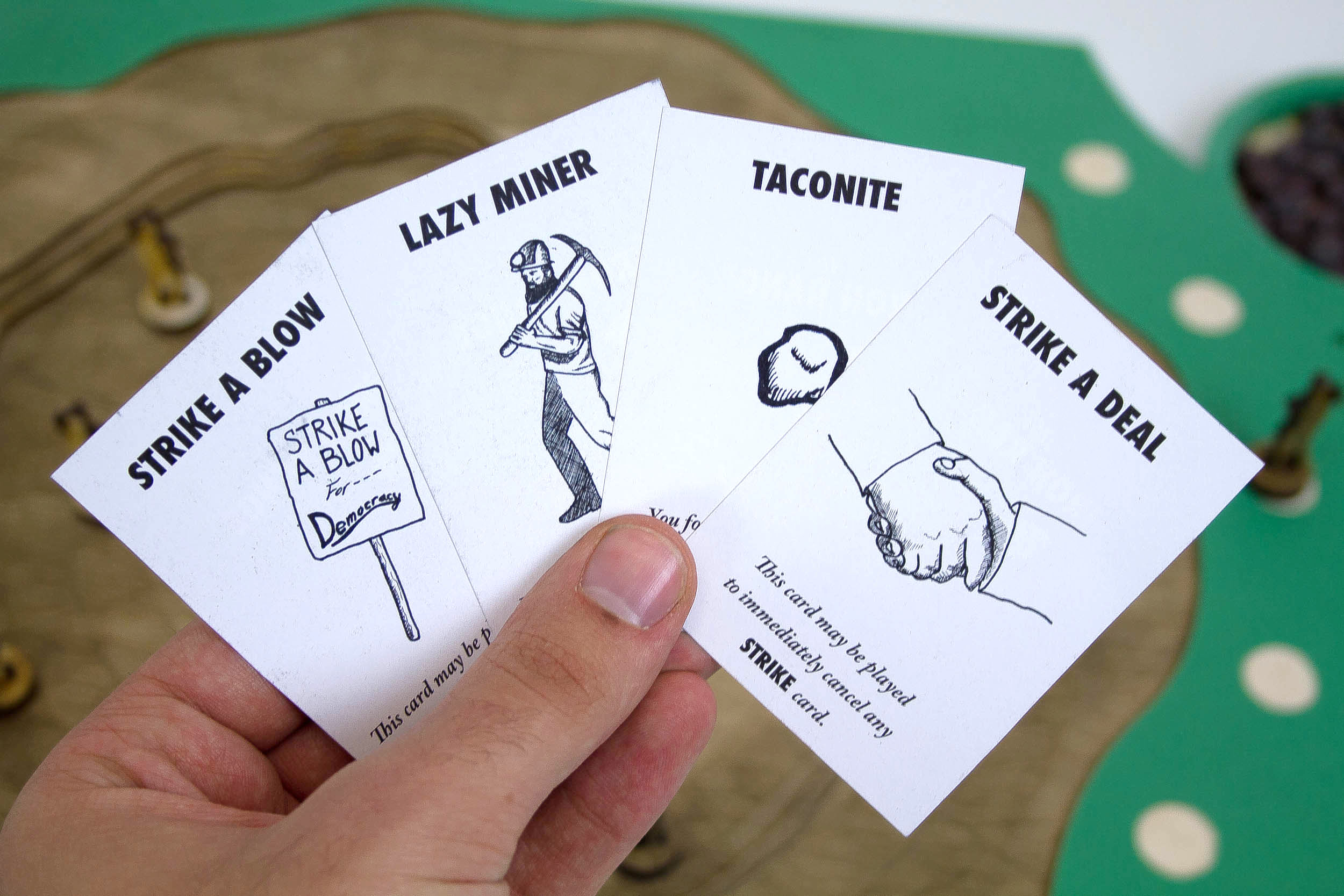

A number of scholarly fields are unearthing the latent connections among labor, automation, and recreation, and games, too, are increasingly adapting the systems of labor and economics into their magic circles. Case in point, the board game The Iron Range tackles the subject of iron mining in Northern Minnesota, set against the backdrop of increasing globalization. The high demand for iron in China as a result of the country’s recent building boom led to Chinese investors buying out Minnesota’s local mines for their taconite (an impure iron ore). Although mining in the region had been in decline, China’s investment has put Minnesotans back to work at now foreign-owned mines.

In The Iron Range, Tyler Stefanich, MFA student in DMA, adapted the mechanics of chess into a new game in which two players run competing mining companies. As they vie to make the most money by deploying their miners on the board—shaped like a circular mining pit—the losing side is eventually “bought out” by foreign investors, which can reverse the dynamic of the game. “This project gave me a chance to explore the boom and bust economics of iron ore mining in Minnesota,” Stefanich said. “I’ve been thinking more and more about labor recently, and the mixed consequences and emotions that globalization evokes. The game provides a way of encountering these complex reactions.”

Real-life’s online dating game: Alright Venus

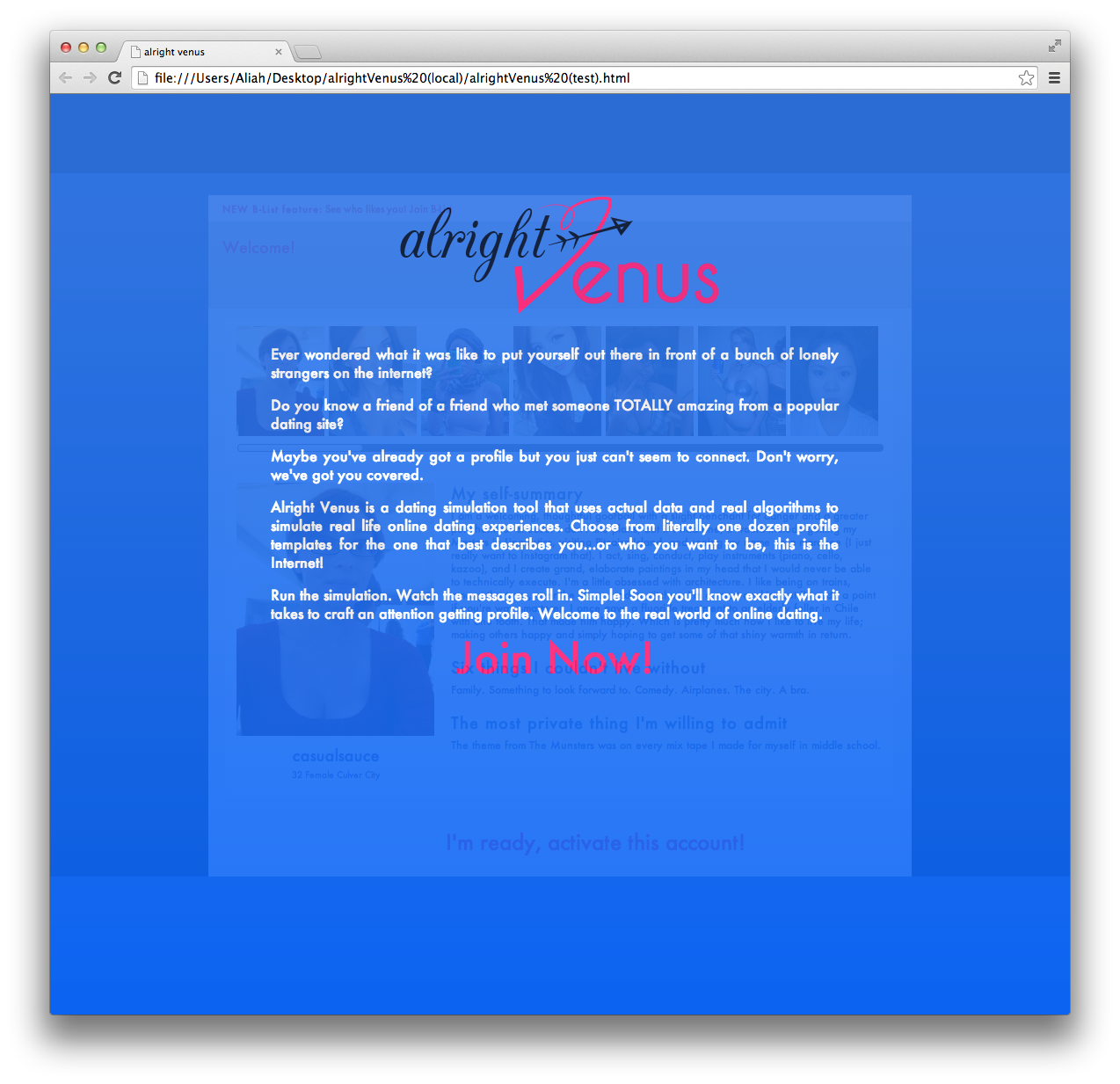

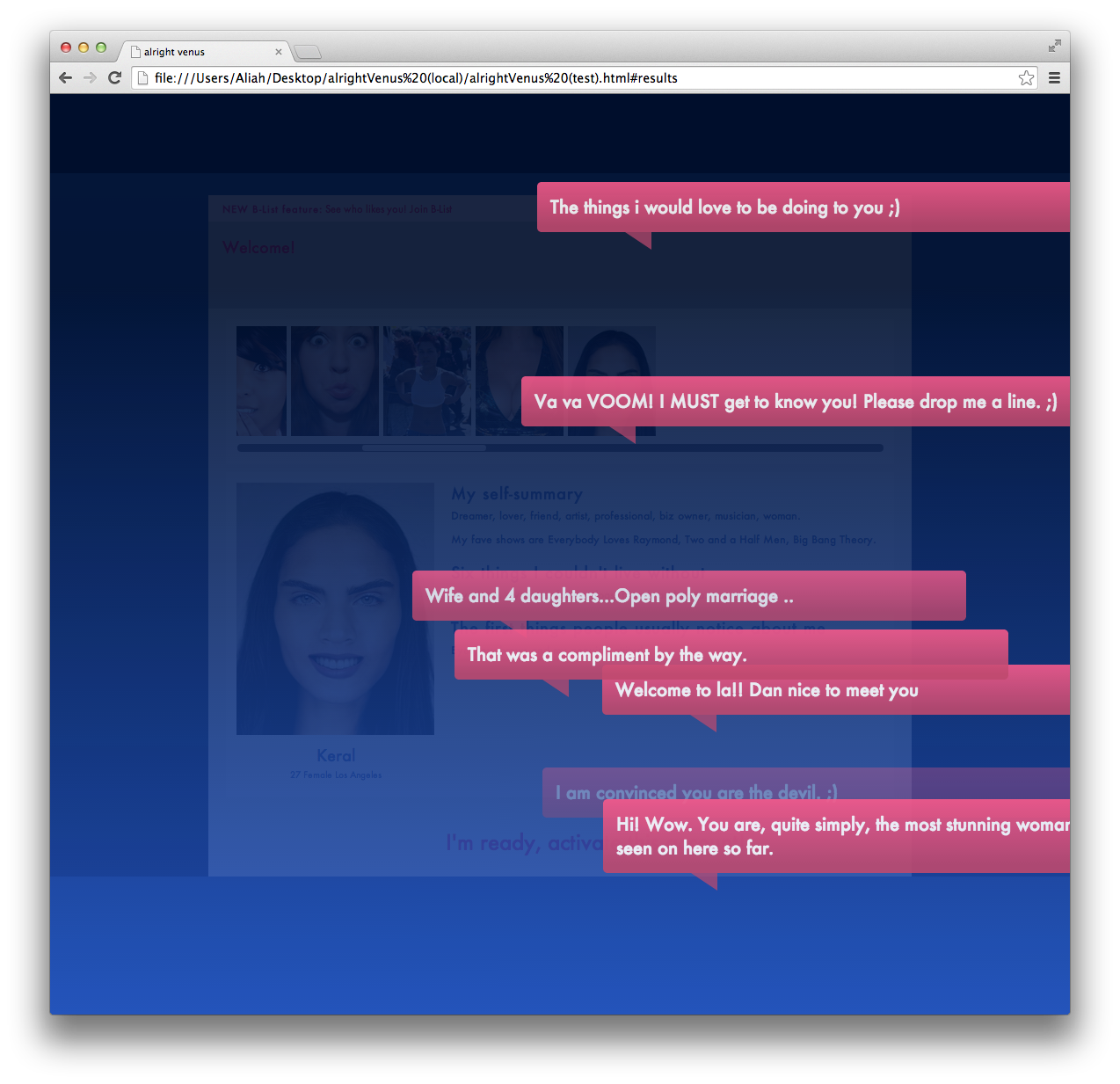

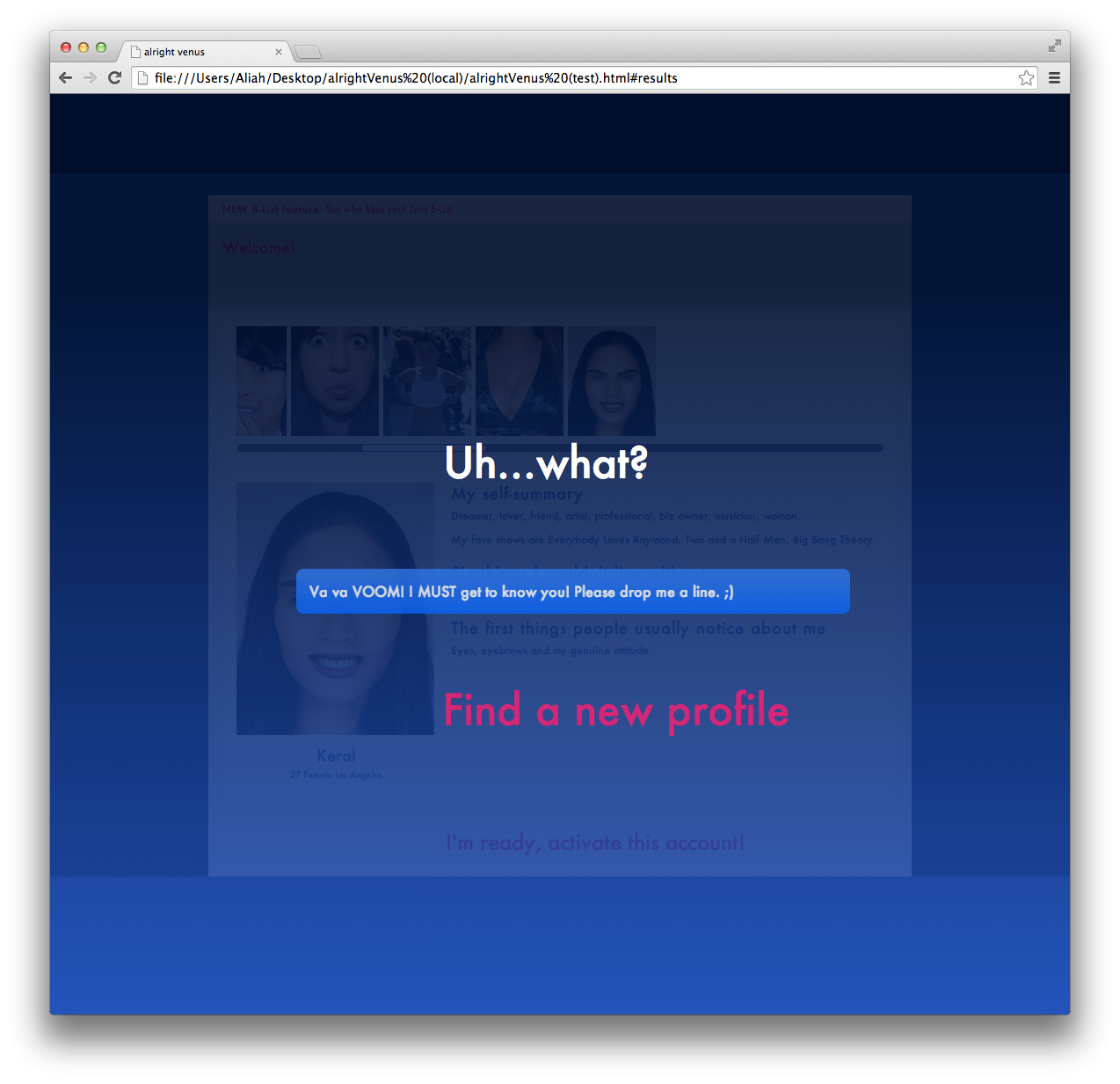

In what game designer Aliah Darke calls “a flight simulator of online dating,” Alright Venus is her latest adaptation of social behavior into game play. A parody of “OK Cupid” and other online dating sites, the game simulates the superficial, absurd, even insulting encounters the plague the search for that special someone. Alright Venus players create imaginary profiles from some twenty different pre-fabricated elements—such as your profile picture—and then evaluate the resulting messages that come in. Darke is drawing upon her own experiences with online dating to make the game and has even included verbatim some of the messages she received online.

“Part of the game’s purpose is to show that, no matter how well you curate the content of your profile, it’s not really about you—people are just checking off their own boxes,” Darke said. “Some profiles will be more successful than others for stereotypical reasons, but there’s no way to ‘win’ the game—which in a lot of ways makes this an accelerated experience of online dating.”

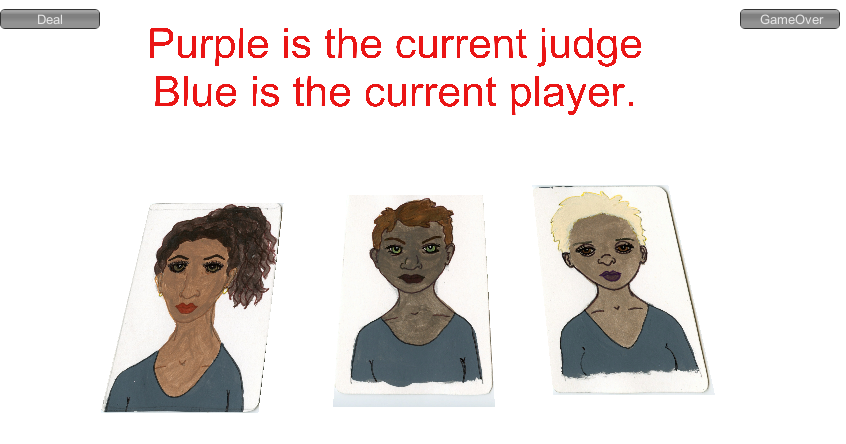

Adapting a card game into a video game: Objectif, the tablet/mobile version

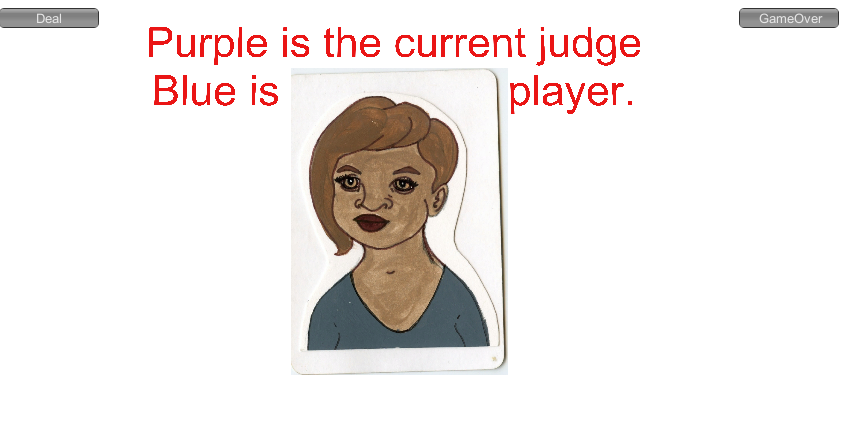

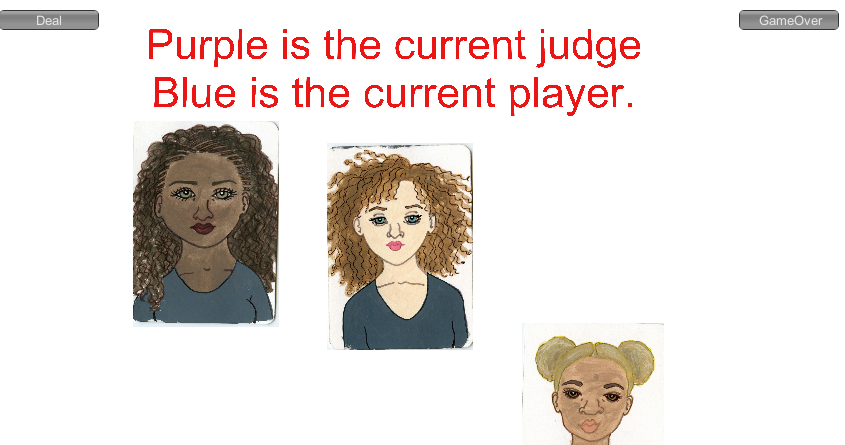

If the comic book and graphic novel can serve as a pre-visualization—a shot-by-shot illustrated story—ripe for adaptation into film, physical games (e.g., board and card) present a similarly attractive form for a video game treatment. Game lab students, in fact, often make playable game prototypes in a physical form before grappling with computer design tools and code. The lab game Objectif, designed by Aliah Darke, uses cards with illustrated portraits of various women to engage the socially and racially constructed idea of beauty. Inspired by the website “Hot or Not” and informed by an article on perceptions of beauty in the journal Psychology Today, the game compels two players to make uncomfortable arguments about who is the most beautiful, based solely on visual information (such as skin color and face shape), while a third player acts as the judge.

Objectif has enjoyed much success at game festivals and in the press, but the current challenge is to adapt the card game into a tablet/mobile version. Student Noemi Titarenco is reworking the game’s mechanics to take advantage of the touch screen interface—an adaptation challenge often encouraged by the lab. Students not only create games in the lab but also make by hand new and retro interfaces, such as the lab’s much-publicized arcade backpack—in which the conventional arcade case becomes a mobile device—as well as cocktail table video game displays and dozens of one-of-a-kind controllers. Adapting a single game to various devices serves to explore the physical, tangible mechanics of game design, and how controller affordance—what buttons and levers can do, how they feel—can profoundly alter game play.

“The biggest obstacle in adapting Objectif is staying true to the way the original game is played,” Titarenco said. “Discussions, arguments—all the human interaction that goes on in the game—we’re working to preserve that in the tablet version, and yet also turn the game into something new. I think we’re on the right track.”

Playing the technical support professional: Satisfaction Guaranteed

David Mershon, UCLA Game Lab Artist in Residence, is currently adapting into game play the pressures and demands of an industry we often encounter from the other end of a phone—the customer support call center. In Satisfaction Guaranteed, the player “works” as a technical support representative of Harmonica Manufacture, a company where the CEO pledged to shut down the business if a single customer ever became unsatisfied. That promise was made fifty years ago, and now the burden falls to the player to live up to it, grappling with calls from unhappy customers and trying to solve their problems—all without losing one’s cool.

As with Japanese “profession” games such as Atlus’s Trauma Center and Capcom’s Ace Attorney series, Satisfaction Guaranteed draws on everyday, real-life roles and then ups the stakes. “Technical support is an interesting subject, but to make a high fidelity, true to life simulation of it was not a desirable outcome,” Mershon explained. “Instead, I found what I believed to be the core challenges of the real-life support profession—solving problems, managing potentially difficult and hostile personalities—and then infused them with the levels of drama and heightened reality that one expects from an exciting video game.”

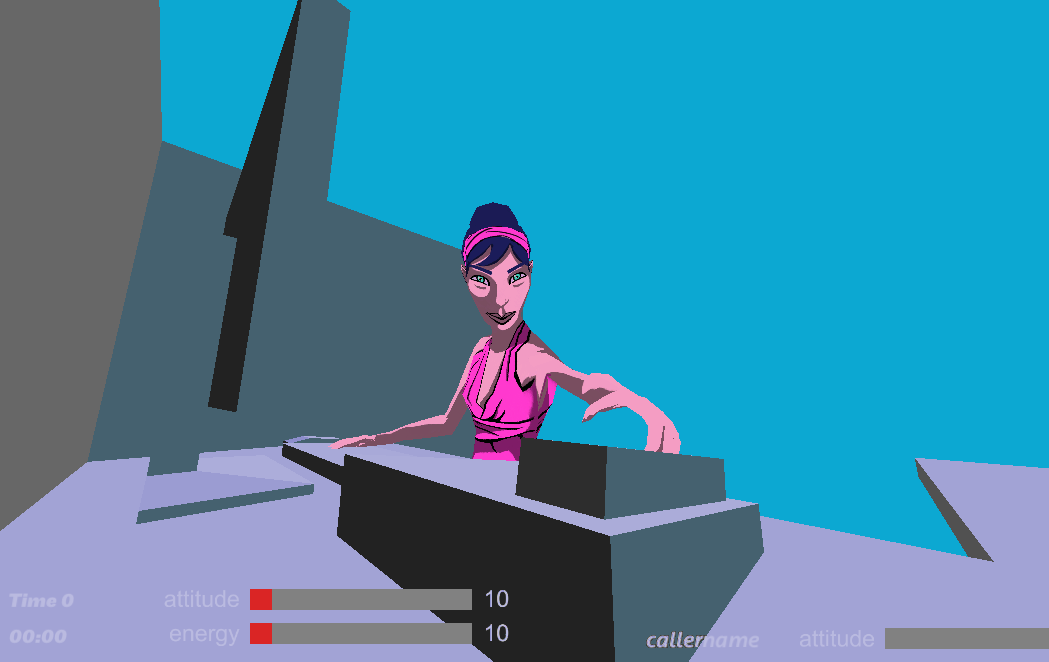

Adapting the cultural artifacts of recent history: Vietnam Romance

In addition to running the lab and teaching game design courses, Eddo Stern continues to develop his own games and art installations. Violent conflicts of all kinds inform Stern’s work, and with his latest game he explores the perversity and absurdity of our collective memory of the Vietnam War, which has fallen into kitsch through cultural commodification. The game, titled Vietnam Romance, will literally stage—as a hybrid live-action theatrical performance and large-screen computer game—an encounter with history and memory, as players and spectators will participate in the game as the winners of an online auction for a guided, conflict-themed trip to Vietnam. As Stern explained, “By combining live theater and computer game elements, I’m trying to unify the emotive, psychological power of the dramatic form as a communal or public experience with the personal implications of choice and decision-making enabled by game play.”

Stern’s own choices regarding the game’s aesthetics will contrast the deeper meaning of game play with a look and feel that match our often fantastical, “flattened” view of Vietnam. Hand-painted and scanned artwork gives the game’s settings and props an illustrative, cardboard-cutout style, and the soundtrack—MIDI chip-tune versions of the war era’s recognizable music—further serves to expose the distortions our cultural artifacts of Vietnam have become.

“As with Vietnam Romance, adaptation serves as an opportunity to subvert—and thereby reveal—aspects of human culture and personal experience that are hard to approach without playful participation,” Stern said. “Games may be defined as mere simulations, but they allow us to adapt the real to get at an experience of the real.”

Playfully subversive: the many roles of adaptation in making games at UCLA Game Lab by David O'Grady is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License