The Curious Adaptation of Benjamin Button: Or, the Dialogics of Brad Pitt’s Face

by James N. Gilmore

“At its most profound, Benjamin Button isn’t about anything more important than [Brad] Pitt’s very handsomeness, which, for a surprising stretch of time, is a wonderful subject to study.” --Wesley Morris, Boston Globe1

Introduction: ‘Benjamin Gump’

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (David Fincher, 2008) identifies itself, both from its title and title card, as an adaptation of the F. Scott Fitzgerald short story of the same name, yet most critics and viewers immediately noted that the film barely resembles Fitzgerald’s prose. Screenwriter Eric Roth (with a screen story by Robin Swicord, who wrote the original drafts years earlier) was widely criticized for writing what was read as a thinly veiled rewrite of his screenplay for Forrest Gump (Robert Zemeckis, 1994). In Button, the titular character (Brad Pitt) mysteriously “ages backwards” across decades of American history, while in Gump the eponymous protagonist (Tom Hanks) impacts American history in serendipitous ways across multiple decades. A comical video from Talkshow with Spike Feresten is exemplary of these criticisms. Clips from both films are juxtaposed in split frames as a narrator lists off similarities between the two: both characters are “handicapped at birth and eventually learn to walk,” they “travel the world, fight in a war, become a hero, and find the girl,” and so forth.2 As literary scholar Kirk Curnutt summarizes, “it became something of a cottage industry for aspiring video editors to splice scenes from the two together to emphasize the similarities.”3 Film critic Amy Taubin put it thusly in Film Comment: “If you line up Roth’s scripts for Button and Gump, they are remarkably similar, narrative turn by narrative turn and literary trope by literary trope. The movies Fincher and Zemeckis made bear almost no resemblance to each other.”4 The implication of these ambivalent criticisms is that The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is most certainly an adaptation, but it is difficult to say what exactly it adapts.

Forrest Gump is just one of many intertexts for Benjamin Button, yet a focus on the textual parallels between the two obscures a more interesting relationship—the use of digital technologies as adaptive devices. That is, Forrest Gump manipulates the texture of the historic archive by embedding Tom Hanks within it, allowing him to “meet” Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. The Curious Case of Benjamin Button digitally reconstructs cities, streets, and, most importantly, ages Brad Pitt’s face across decades. Both of these uses of digital technologies rely on a sort of ironic distance: we know, for instance, that Tom Hanks didn’t really meet President Kennedy, and so, in media scholar Vivian Sobchack’s terms, “Forrest Gump conflates and confuses the fictional with the historically ‘real’ in an absolutely seamless representation.”5 Similarly, we know Brad Pitt is not 70 years old, and yet we recognize the character’s face as his own. Whereas Gump adapts the historical archive, Button adapts the star image. Digital technologies reemphasize the star as a site of meaning creation, as the site of adaptation itself. Propelled beyond a desire to see Pitt “in the flesh” as opposed to “in the pixel,” Benjamin Button lets him transcend his body and turn back the clock to the very birth of his star image. As film critic Todd McCarthy wrote in his review for Variety, “truly the most unnerving image is Pitt looking more or less the way he did in Thelma and Louise, or at least half the age of the man playing the character.”6 This “unnerving image” of a digitally recreated “young” Brad Pitt re-embodying the ostensible moment of his stardom, his Ur-image, is predicated on a dialogical engagement with Brad Pitt’s face, and it is through this moment that we can engage the film as a digital adaptation.

This article argues that the adaptation of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button cannot be explicated through debates about fidelities or resonances across literary or cinematic narratives. Instead, I argue that digital technologies play a significant role in adaptation practice, and as such we need to consider adaptation as, in part, a technological act. My analysis of the film’s uses of digital technologies will be aided in part by official accounts of the film’s production, such as the DVD documentary The Birth of Benjamin Button. These works discursively emphasize digital technology as a form of adaptation through images, videos, and interviews about effects labor, in part demonstrating the significant amounts of erasure that occur alongside the construction of digital performances—living actors are partly voided to make room for Brad Pitt’s face and digital effects workers express invisibility as their primary goal. Their invisibility places greater emphasis on Brad Pitt’s face as the film’s key analytical site; obsessively constructed, hugely expensive, and predicated on a dialogical relationship, I argue that Benjamin Button can best be understood as a film about the adaptation of the face and the implications of its iconic power in digital cinema.

Textual Mosaics: Intertextual Dialogism and Post-Celluloid Adaptations

My analysis draws on cinema studies scholar Robert Stam’s ideas of intertextual dialogism from his chapter “Beyond Fidelity: The Dialogics of Adaptation,” where he accounts for the polysemous ways one might “read” an adaptation. Incorporating an expansive view of intertextuality brings to adaptation theory the notion that the text “is not closed, but an open structure…to be reworked by a boundless context.”7 Indeed, any particular text is “an intersection of textual surface” with “infinite and open-ended possibilities generated by the discursive properties of a culture.”8 Stam sees this infinite discourse as part of the text’s pleasure, as a potential site for both analytical playfulness and serious methodological consideration of how texts open and close meanings. Media scholar Gunhild Agger, however, cautions that infinity entails “a loss of perspective, to the point where origin, context, and purpose fade and results become uncertain.”9 At some level then, the discourse must be bounded by some kind of economic, cultural, or other context that constrains its potential infinity. In this article, a shift from literary to digital discourses opens up we always feel its presence shadowing the one we are experiencing directly,”10 where our memories or prior experiences of related texts help organize textual pleasures. In Benjamin Button, it is not only our memories of Forrest Gump that might provoke meaning, but also our memories of Brad Pitt and our astonishment at the adaptation of his face.

Establishing a vocabulary to explain the threads acting upon a given textual surface, Stam turns to literary theorist Gerard Genette and the idea of transtextuality, which is characterized by “all that which puts the text in relation, whether manifest or secret, with other texts.”11 One of transtextuality’s key dimensions is hypertextuality. Hypertextuality analyzes relationships between a hypertext and a hypotext, wherein “the former transforms, modifies, elaborates, or extends” the latter. In this “endless process of recycling, transformation, and transmutation, with no clear point of origin,” it becomes necessary to mark meaningful signifiers as guideposts for deriving meaning from the textual interplay between the hypertext and hypotext.12 The critics who opened this article might, for example, consider Benjamin Button hypertextual work modifying a hypotext like Forrest Gump. I would rather see the hypertext as digital technology itself—or rather, digital cinema or any equivocal term that might connote the vast number of ways that digital reshapes film production and distribution. The hypotext becomes the film itself; shot on high definition digital video, edited on computers, rendered as files instead of celluloid strips, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is a film thematically about death that also stands on the threshold of film’s own “death.” Rather than explore the entire film as a hypertextual relationship between celluloid and digital video—a task I certainly consider exciting if far outside the scope of this article—I instead want to concentrate largely on the form of Brad Pitt and read him, or rather the star image of him, as the key hypotext, as not just a body but also an icon that is transformed in a variety of ways by hypertextual digital means.

Agger, in working to bridge the gaps between literary and media studies’ employment of these terms, turns to the more open-ended idea of the mosaic: “The very notion of representation [is] replaced by a textual system with its own system of reference; the narrative is replaced by a textual mosaic.”13 This mosaic, for Agger, invokes philosopher Julia Kristeva’s notion of the “double orientation” of the word (or sign), and how “choosing a particular word establishes a certain orientation toward the receiver,” orienting a particular intonation with previous intonations.14 This article, then, considers the reverberations and orientations of Brad Pitt as a function and form of the mosaic. The “mosaic” further suggests the broadly infinite concept of intertextuality might also take the form of a “network,” of different sources feeding into and out of each other, where the creation of meaning is entirely dependent on how the viewer plugs into a network’s port, or how many ports they explore. Brad Pitt’s face, then, is just one of many ports—the Fitzgerald short story and Forrest Gump constitute two others—for analyzing Benjamin Button as an adaptation.

Philosopher and theorist Mikhail Bakhtin’s work on dialogics has further implications for the underpinnings of this study. For Bakhtin, “genuinely participative thinking and acting requires an engaged and embodied—in a word, dialogical—relation to the other, and to the world at large.”15 Bakhtin’s notions of intersubjectivity relate how the ‘I’ and the ‘you’ rely on each other to construct meaning—while we have our own experiences and our sense of the world, recognizing other people forces us to place our own worldview into conversation with their own and thus construct interrelated, or adapted, meaning. In his words, “the body is not something self-sufficient: it needs the other, needs his recognition and form-giving activity.”16 For adaptation, we might use the dialogical to suggest that even though a film of a book is its own text, the relationship to an original source continually creates potential meanings. As scholar Michael E. Gardiner summarizes, “we must realize that every aspect of consciousness and every practice a person engages in is constituted dialogically, through the ebb and flow of a multitude of continuous and inherently responsive communicative acts.”17 Art follows similarly: in discussing the novel, Bakhtin notes it “denies the absolutism of a single and unitary language [by incorporating] the languages of social groups, professions and other cross-sections of everyday life.”18 The dialogical relationships at play in an adaptation are not simply between source and screenplay, but also, to borrow from the structuralist camp, between an array of signifiers. Digital technologies facilitate dialogical relationships between shifting images and experiences in a given text through creating fantastical images grounded in some relationship to iconic reality. Brad Pitt’s face, then, becomes the site through which dialogical meaning is constructed. It is transformed yet intimately familiar.

In analyzing the adaptive function of digital technology in Benjamin Button, I invoke media scholar Costas Constandinides’s model of post-celluloid adaptation. Building off adaptation and digital media theory in his book From Film Adaptation to Post-Celluloid Adaptation, Constandinides utilizes Stam’s notion of “post-celluloid” as “the computerization or digitization of media,” suggesting “adaptation within the context of cinema studies must be considered in the light of these technological changes.”19 Constandinides defines post-celluloid adaptation as “the process whereby a preexisting fictional source expressed in a traditional medium (novel, film, television) is recreated, directly or not, in a new medium (digital cinema).”20 This theory argues that a “multiplicity of texts”21 act on and within a single media text. So what might it mean to think of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button as a post-celluloid adaptation? While Fitzgerald and Forrest Gump might take us down several narrative transformations certainly worth considering, a post-celluloid study would push beyond the comparative mode offered by traditional adaptation studies.

Indeed, these paths of comparative analysis on Benjamin Button have been well tread, more often than not coming up with the unsatisfactory conclusion that Button is simply too different from Fitzgerald—“It fails on too many levels, and is not really a Fitzgerald adaptation”22 —or too derivative of Forrest Gump. The multi-author piece “The Case Gets Curious: Debates on Benjamin Button, From Story to Screen” from The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review takes a number of perspectives on the ramifications for this kind of flagrantly unfaithful literary adaptation, as does scholar Mark Browning’s chapter on the film from his book David Fincher: Films That Scar. Browning argues that a focus on the visual effects “has served to obscure consideration of wider elements of the film, such as the highly derivative nature, its narrative structure and characterization, and the relationship to its literary source material,”23 yet I must disagree: the textual/literary debate has backed discourse into a corner. Considering Benjamin Button as a product of digital cinema bound up in the process and significance of its visual effects—as an adaptation concerned with the adaptive powers of digital technology—allows us to break free of largely self-fulfilling narrative discussions. This is not to dismiss the work others have performed on Benjamin Button’s adaptation to date, but rather to point to a need to shift the conversation in order to find deeper nuance in the film.

To think of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button as a digital cinema text entails recognizing how digital video and effects act upon the text. My analysis of the film and its labor thus argues that the idea of post-celluloid adaptation offers fruitful ways to think about digital cinema texts. Beyond recognizing what digital effects are creating, recognizing why and how it transforms the indexical qualities of the cinematic image provides a more complex understanding of how discourses operate within digital cinema and around adaptation. I turn now to two complementary sections about the meanings of digital effects in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. I first use paratextual discourse to provide an understanding of how these digital effects are predicated on a tension between creation and erasure. I then turn back to the film to engage Benjamin Button as an intertextual dialogism between digital technologies and star images that foregrounds our relationship with the star’s iconicity and plasticity.

The Curious Effect of Benjamin Button

My understanding of how Benjamin Button—the character—is rendered throughout the film relies heavily on discursive constructs: interviews and audio commentary from director David Fincher, paratextual information provided in the documentary The Birth of Benjamin Button, and popular discourse praising and exploring the production of the effects. This analysis is purposefully guided by official accounts in part because I want to understand effects labor as a discursive construct—how do “official” texts ask us to understand technology, and how does that understanding transform our relationship to the film text? My thinking comes largely out of Jonathan Gray’s work on paratexts,24 but also the work of media industries scholars like John Caldwell.25

These paratextual sources depict a vast range of processes and technologies, providing both detailed technological explanations and also visual catalogues for their operations. For example, in his audio commentary for the film, David Fincher details the animatronic work of the Benjamin Button baby: “This is a radio-controlled baby … [a] puppet which requires three guys to make it wiggle around.”26 On the subsequent making-of documentary on the DVD’s second disc, there is footage of three men moving remote controls to make the baby Benjamin squirm on the bed in the old folks’ home. Benjamin Button begins the film in analog, as a robot who functions in a predetermined range and at the behest of multiple laborers. This shot of three men and a baby is microcosmic of the effects process: the body represented in front of the camera portrays life because of the work behind the camera, yet those who “give life” erase any trace of their own presence. In a sense, the effects labor of Benjamin Button constitutes a longstanding tradition of Hollywood, where “several different bodies may be used to construct a single performance: voices are dubbed, stunt artists are used for dangerous action sequences, and sometimes hand models and body doubles provide body parts to substitute for actors.”27 There is, then, nothing altogether strange about Cate Blanchett performing the voice for every incarnation of Daisy from ages eight to 86, but there is something startling in how digital manipulation can mask the index of Blanchett’s voice, changing its pitch and making it more childlike or aging it beyond her natural ability. Again, digital technologies are adaptive, taking what exists and transforming it, making it something other and yet something with greater diegetic verisimilitude.

More than masked labor though, Benjamin—as an effect—is also masked capital. Fincher remarks somewhat off-handedly during his audio commentary about a shot of Benjamin sitting in the corner of a crowded frame, calling it “a $20,000 effects shot just to have him in a sea of faces.”28 Throughout his commentary, Fincher continually points out moments where Benjamin lingers in the edges of a frame, or where he appears briefly in a shot before the camera pans away from him. He says, “he’s there and he’s doing what Benjamin would do, but it’s not like it’s framed and always supported as a big money shot.”29 These accumulating moments are in effect accumulating capital, such that Brad Pitt’s face is not merely a technological marvel, but it also becomes literally equated with money. This too, can be read alongside discourses that value the star image as a prized commodity for the selling of a film; Pitt’s face in this logic becomes the locus not only of capitalist expenditure but also a key means of establishing the value of the film.

Substantial discussion of effects labor is not just confined to the DVD paratexts. Discourse about them circulated quite heavily upon the film’s release, either in popular press praise or in any number of magazine profiles on the making of the film. Barbara Robertson’s somewhat technically focused article “What’s Old Is New Again” from Computer Graphics World is indicative of the popular visual effects discourse. Nearly from the outset, Robertson states, “creating a digital human is difficult enough, but two things made this particular task especially thorny. First, Pitt has one of the most recognizable faces in the world.”30 The laborers themselves worked intertextually with and struggled against Pitt’s recognizability; his iconic face both posed challenges and also aided the labor process. The article details how Digital Domain, the company chiefly responsible for the film’s special effects, used technology from over a half dozen other companies and developers for the various tasks required of the post-production. Further, “at the peak of the project, 155 artists worked on the film, with most spending a year and a half creating and refining shots, some of which took more than 100 iterations to nail down.”31 I list the number of employed workers in part to demonstrate how this discourse recovers the labor that is lost on the screen, but also for how it fractures the presumably unified image of Brad Pitt’s face. Said Ed Ulbrich of Digital Domain, “We built a library of micro-expressions constructed from bits and pieces of Brad so we could assemble a performance of what Brad really does. We aren’t interpreting his performance. We have [encoded] the subtleties of how Brad’s brain drives his [facial] muscles.”32 Thus, intertextuality exists even at the level of labor, with Pitt’s performances adapted and expanded through effects production.

These discourses further demonstrate how digital technology creations include a simultaneous erasure. For Benjamin Button, the flesh and blood actors such as Robert Towers have their faces wiped from the image. Focusing attention on digital technologies shows how any adaptation is a process of work, and how transformation entails the necessary loss of some elements, such as a “real” face, in favor of creating a new and more meaningful “constructed” face. Benjamin Button himself is the result of adaptation, a curious dialectical effect embodying and erasing the work of hundreds of people and millions of dollars. The brunt of that work is focused on Brad Pitt’s face, and so it is that face that harbors the dialogical possibilities and the adaptive potential of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

The Dialogics of Brad Pitt’s Face

The relationship between adaptation and the star image is predicated on our recognition of Pitt’s body from other moments of his career. Brad Pitt’s body is an icon Fincher has himself previously engaged, most notably in Fight Club (1999). In that film, Pitt plays the hyper-masculine, anti-consumerist anarchist Tyler Durden. Fincher uses Pitt’s image self-reflexively—his body is constantly fetishized for the camera, with various degrees of slow motion and aestheticized lighting encouraging us to see Pitt as a masculine ideal. At one point, Edward Norton’s character asks Durden, while gesturing towards a Gucci ad of a man in underwear, “Is that what a real man looks like?” Durden laughs at the question, but it is a joke the film is in on: Pitt/Durden is idealized only to reveal that he is a figment of Norton’s imagination—he is Norton’s alter ego, his id, a Mr. Hyde to his Dr. Jekyll and, most importantly, a commentary on the unattainability of Brad Pitt as a masculine ideal. The implicit critique here is that Brad Pitt, or rather “Brad Pitt” as an icon, does not himself exist, at least publicly: he can only be grasped as the assemblage of all his utterances and constructions; he is a star, a cultural form, a product of his representation that is itself an effect.

Our relationship with Brad Pitt as a star, as a constructed image, is key for our affective relationship with Benjamin Button. Elsewhere, I have written about the complex phenomenological relationship with a digital body in the Hulk films, examining how the digitally created body is negotiated against discourses of photorealism.33 Whereas a character such as Hulk, or Gollum from The Lord of the Rings, is markedly not human and thus easier to negotiate as a spectacle—a conscious presentation of an effect—the haptic or phenomenological qualities of human beings are problematic for computer-generated laborers.34 And unlike other films such as director Robert Zemeckis’s work with motion capture (The Polar Express [2004], A Christmas Carol [2009], Beowulf [2007]), Benjamin is often one of the few computer-generated aspects in an otherwise “real,” or digitally photographed space. Like the various mutations of Jim Carrey in 2009’s A Christmas Carol, we also search for the recognizable icon of Brad Pitt within the makeup and digital rendering. As Fincher says, “It occurred to me that this might be a better place to put the audience if this was somebody that you really knew what their face looked like, because you could peer into it and kind of go, ‘I know who that is, how do I know?’ … When you could see it was him, there was something sort of exciting about that.”35 To recognize Brad Pitt beneath the effects is thus to recognize the effect itself, and in turn to rip its seamlessness apart. We could investigate this break similarly along the lines of photorealism—the film attempts to create realistic images that are never meant to be mistaken for real images—but I would rather consider Brad Pitt as part of the intertextual relay, as part of the public images and icons that inform our reading of the film.36

This intertextual relay, as Fincher continues, is precisely the point: “You’re talking about someone who you can’t walk thirty-five feet in the tittilized world and not see a picture of him; I mean literally like every ten seconds, here he is getting on his motorcycle … here he is having a snow cone. In a weird way it kind of helped us.”37 The intertextual relay that constitutes and constructs “Brad Pitt”—his paparazzi photos on websites and tabloids, his display in advertisements such as Chanel, his own work in films, interviews he has conducted that have been placed online, etc.—becomes an essential element of how Benjamin Button anticipates an affective relationship with Pitt/Button, and how we can think of this as key to the film’s broad ideas about adaptation. Brad Pitt exists, then, alongside discourses of Hollywood stardom. Here I am building partly off Richard Maltby’s accounts of the “dual presence” of stars in Hollywood cinema, where “our impressions of an actor’s presence and his or her ‘disappearance’ into character readily alternate with each other.”38 Further, “in every performance, two identities—actor and character—inhabit the same body, and…the technical skill of the actor consists in eliding the difference between the two identities, in disembodying himself or herself to embody the role.”39 The few personality traits Benjamin Button ever exhibits as a character puts increasing weight on Brad Pitt as a structured icon, embodying not necessarily a role but a mode of technological production. It is, further, almost impossible to discuss star images without gesturing towards Richard Dyer’s magisterial work on the subject.40 Whereas Dyer considers the star image as a social construct, this invocation of Brad Pitt seems less concerned with the socio-political aspects of his image or its circulation and more with his image as an image; that is, as a visual icon. In turn, the social dimensions of Pitt’s masculinity are repressed in favor of exploring its affective dimensions. Button posits the face as a public image, one that we are intimately familiar with and asked to engage throughout our spectatorial experience.

Throughout the film, we are asked to look at Pitt’s body. In some instances, this act of looking might entail marveling at the technology of aging his face and seamlessly placing it atop another actor, such as when Benjamin admires his growing muscles in the bathroom mirror. There are at least three moments in the film where Benjamin admires his reflection in a mirror, as if inviting us to contemplate his changing body and the gradual emergence of Pitt’s iconic image. At other moments, the camera provides an excess of Pitt’s body. For example, when Benjamin travels to Paris after Daisy’s accident, he takes a seat in the hospital waiting room. As he begins a voiceover, the scene cuts to a close-up of his feet; the camera then tracks up his body, resting on a profile view of his face. This shot serves no ostensible purpose; it is completely divorced from the dramatic development of the sequence. Instead, it occurs on some other, narratively excessive level, to borrow Kristin Thompson’s term.41 It must be read, I would argue, in terms of the film’s preoccupation with Benjamin’s/Brad’s body, providing us a moment to ponder him from the feet up. This shot pays off just a moment later when Benjamin sits at Daisy’s hospital bed. We are invited to share her point of view via a close-up of Pitt that slowly comes into focus; after a moment, she remarks, “My God, look at you. You’re perfect.” Upon uttering this line, the sequence cuts to a mostly frontal close-up of Benjamin’s face, as if to confirm that yes, Brad Pitt is finally perfect. He is the masculine ideal. There is, in this moment, no prosthetic or digital enhancement (save the scar that Benjamin sustains during combat in World War II). There is only the star image circa 2008. While in a sense this close-up operates in a typical Hollywood conception of space and framing for a conversation sequence—shot-reverse shot is employed across a fairly defined axis of action as Benjamin and Daisy talk—the use of close-ups also operate dialogically with the film’s other close-ups and, beyond that, with our extradiegetic history with Brad Pitt’s face.

The close-up becomes the film’s meditative site, a site that is announced in no less a place than the posters for the film itself, almost all of which include a close-up of Pitt’s face. The isolated face, in Béla Balázs’s terms, “takes us out of space, our consciousness of space is cut out and we find ourselves in another dimension: that of physiognomy.”42 The continuous play of isolated faces—of Pitt’s constantly changing physiognomy—allows us to reflect on the changing nature of faces: digital technologies adapt the very physiognomy of the human face, creating a different kind of “cut out space.” Perhaps it is better to turn to Roland Barthes’s “Garbo’s Face,” where he describes Greta Garbo as representing “that fragile moment when cinema is about to extract an existential beauty from an essential beauty.”43 Through its extensive labor and its pervasive occupation with changing faces, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button attempts to reclaim that existential moment and, further, to make the face both an Idea and an Event, in Barthes’s terms. Digital technologies allow us to revel once more in the physiognomy of the face by shifting it constantly, by making the face a spectacle of technology and of labor.

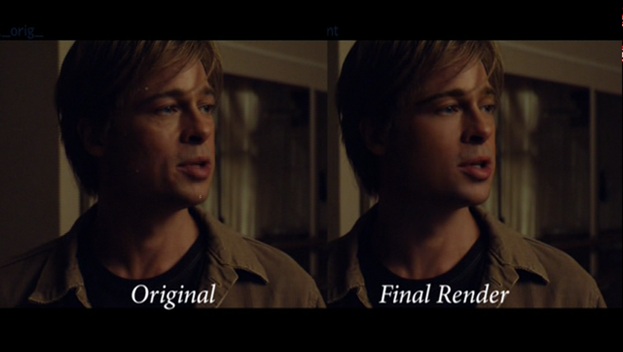

Finally, I would like to consider the moment of “Young Brad,” which Fincher calls “the culmination of all the digital trickery,”44 and which I consider the climax of the film. It is here that Brad Pitt’s face as both Idea and Event coalesces. This sequence, and the process used to create it, as it is explained in The Birth of Benjamin Button, invokes various discourses about celebrity images and the impulse to remake celebrity youth, to freeze stars in their moment of iconic perfection via surgeries and chemicals. The company that performed the effects in this sequence, Lola Visual Effects, calls their process “DCE—digital cosmetic enhancements,” and refers to their work as “doing digital facelifts.” Digital effects, in their rhetoric, are a safer, seamless method of removing bags from under actors’ eyes and of erasing wrinkles. Their work is usually meant to fool the audience into thinking an actor looks a particular way; for Benjamin Button, however, they push their technology to its limits, “using the compositing tool to turn back the clock twenty years and remove the artifacts and the lighting and remove the wrinkles and adjust the tissue density.” They even employ a Beverly Hills-based plastic surgeon, whose advice is “very specific and scientific.” This process is called “Youthenization,” a playfully perverse pun on “euthanization.”45 But where the latter word heralds impending death, the former attempts to transcend death, to allow the star to circumvent the flaws of their material body.

De-aging Pitt twenty years places him at approximately the age when he appeared in Thelma and Louis (Ridley Scott, 1991). In that film, his shirtless seduction of Geena Davis propelled Pitt—Pitt’s body?—to a fetishized stardom. In her work on Pitt’s image in and after Thelma and Louise, media studies scholar Cynthia Fuchs argues his career choices operate alongside and against this breakout image. He pursues roles “that run counter to his conventional movie stardom,” making “explicit efforts to debunk the petty and pretty boy rep.”46 Further, she cites interviews, such as his 1999 piece for Rolling Stone that demonstrate Pitt as someone who “understands himself in relation to those who read, judge, and worship him.”47 Brad Pitt reflexively understands how he is “Brad Pitt,” both as a symbol of masculinity, an icon of handsomeness, and a commoditized form. But what does it mean for The Curious Case of Benjamin Button to intertextually recall this moment? This sequence explicitly recasts the film as a dialogical engagement with Pitt’s star image, as about “Pitt’s very handsomeness.”48 Throughout the sequence, Pitt moves in and out of shadows, his face often lit in a quasi-chiaroscuro manner or shot totally from behind. The reason for this may be practical, minimizing the amount of effects shots in this sequence, but it also continually teases us with his youthful face. He is first shown in this sequence in long shot, completely in shadows. When he steps into the light, he is lovingly lit in close-up, revealing his youthful complexion to Daisy and to us. There are two more instances in this sequence of Benjamin moving from darkness to light; this motif serves to continually present, and indeed almost fetishize the revelation of Young Brad Pitt.

Reading this as the film’s climax—as the ultimate payoff of digital technology’s adaptive capabilities—prompts further re-readings of other moments in the film, such as when Benjamin forlornly tells Daisy, “I was just thinking about how nothing lasts, and what a shame that is.” Ostensibly, this is a key thematic line for the film’s preoccupation with death. While the narrative explores death and the slow erosion of time, the technology attempts to rebuke death, to assert that the digital allows an artificial sustenance. Like the reverse ticking of Mr. Gateau’s clock, Young Brad Pitt is a testament to our unending desire to transcend death, and the possibilities of reimaging our bodies. As English scholar Kathryn Lee Seidel remarks, “To see Brad Pitt as old is to understand that we will all grow old.”49 It is the yearning for rebirth then, and not the fear of death that is at the heart of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, a meaning that can only be grasped by reorienting the way we consider the dialogical terms of adaptation in digital cinema.

Digital technologies in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button foreground bodies and time. In his famous piece “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” film theorist and critic Andre Bazin discussed the “charm” of family photographs, where unlike the slightly abstracted representational qualities of the portrait, the facsimile of the photograph instills “the rather disturbing presence of lives halted at a set moment in their duration, freed from their destiny … by the power of an impassive mechanical process: for photography does not create eternity, as art does, it embalms time, rescuing it simply from its proper corruption.”50 It is hard to watch the image of Young Brad Pitt in Benjamin Button and not consider this passage. While cinema has a long history of using makeup to alter the appearances of its stars—aging them, beautifying them, or otherwise masking them under some sort of prosthetic—the digital technologies in Benjamin Button attempt to “free” its subject from the destiny of his aging in an altogether different way. Instead of memorializing “Brad Pitt” in the moment of his being 44 years old, the film attempts to rescue Pitt’s iconicity from time itself.

Addendum: The Politics of Brad Pitt’s Face?

This article has used The Curious Case of Benjamin Button to continue a debate about what digital cinema adapts and transforms from its analog, celluloid counterpart. Arguing that traditional conceptions of adaptation—i.e., relationships to literary or cinematic sources and interpretations of fidelity and transformations—can only take us so far in the vast network of discourses acting upon a single text, I turned to the figure of Benjamin Button himself, reading him as an effect of digital cinema more than a character, relying less on character traits than on the spectator’s intertextual relationship with actor Brad Pitt’s star images. As such, I also argued that Benjamin is predicated on an erasure of labor that underlies much of contemporary digital effects-driven filmmaking. While the paratexts surrounding the film allow us to recover a sense of labor, so too does Pitt’s face attempt to transcend the specter of death that haunts Benjamin Button. But what other implications might this relationship to the star image have, and indeed how else might we continue to read Pitt’s particular star image beyond its intrinsic qualities of handsomeness and “perfection”?

In lieu of a traditional conclusion that might end this argument, and because the notion of dialogics suggest an infinite opening up rather than a systematic closing down, I would like in these concluding paragraphs to gesture towards one possible avenue that considers Pitt’s expanding role as a film producer, particularly by focusing on another recent adaptation—12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013). Pitt’s production company, Plan B, has been a co-producer on a number of the star’s recent films, including Killing Them Softly (Andrew Dominik, 2012) and perhaps most famously World War Z (Marc Forster, 2013). The latter film was dramatically reshot due to budgetary concerns, and the reworked final act places significantly greater importance on Pitt’s character as potential savior of the human race in its fight against a zombie apocalypse.51 This figure of Pitt-as-savior carries over into 12 Years a Slave, where he plays Bass, the carpenter who ultimately arranges for wrongly-enslaved Solomon’s (Chiwetel Ejiofor) freedom from cruel slave master Edwin Epps (Michael Fassbender). Here, the lines between Pitt-as-actor, Pitt-as-star, and Pitt-as-producer blur in bizarre ways. As a character, Bass is a deus ex machina, a figurative angel—a white savior—who rescues Solomon. Reading between the diegesis and the production history, however, Pitt’s crucial role in developing 12 Years a Slave through his Plan B production company recasts Bass—or rather, Pitt’s performance as Bass—as deriving more from a reflexive discourse on Pitt’s own ideology as a burgeoning film producer.

As Pitt’s credits as producer widen, then, it will become increasingly important to see how he finances his own star image, and how the politics of his image develop alongside Plan B. Benjamin Button offers a case study for how we might negotiate Pitt’s image in relation to the contexts, narratives, and technologies producing it. Applying the terms of contemporary adaptation theory to both star images and digital effects labor expands how we might conceive of adaptation’s boundaries as a mode of discourse and of meaning-production. To experience a text as an adaptation, as Hutcheon advocates, and to open ourselves to the experience of adaptation as such, is to account for the numerous intertexts and changes at work within a given text, to see the relationship between hypertext and hypotext not just operating on the narrative or the cinematic work as a whole, but within and across individual shots, aesthetic motifs, modes of production, and types of labor.

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank Nick Browne for his comments on a very early version of this article.

NOTES

- Wesley Morris, “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” Boston Globe, 25 Dec. 2008 (Link accessed 01 Feb.) 2014.

- “The Curious Case of Forrest Gump,” Talkshow with Spike Feresten, (Accessed 9 Mar. 2012.)

- Kirk Curnutt, “Stories Without Centers,” in “The Case Gets Curious: Debates on Benjamin Button, From Story to Screen,” The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review, Vol. 7: 2009, 3-33, 7.

- Amy Taubin, “From Cradle to Grave,” Film Comment, Jan.-Feb. 2009, 30-35, 35.

- Vivian Sobchack, “’Shit Happens’: Forrest Gump and Historical Consciousness,” Ilha do Desterro, no. 32 (1997), 15-26, 18.

- Todd McCarthy, “Review: ‘The Curious Case of Benjamin Button’,” Variety, 23 Nov. 2008, (Link Accessed 01 Feb. 2014).

- Robert Stam, “Beyond Fidelity: The Dialogics of Adaptation,” in Film Adaptation, ed. James Naremore (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2000), 54-76, 57.

- Robert Stam, Ibid., 64.

- Gunhild Agger, “Intertextuality Revisited: Dialogues and Negotiations in Media Studies,” Canadian Aesthetics Journal, Vol. 4 (Summer 1999), Accessed 4 Feb. 2014.

- Linda Hutcheon, A Theory of Adaptation (New York: Routledge, 2006), 6.

- Quoted in Stam, ibid., 65.

- Stam, ibid., 66.

- Gunhild Agger, ibid.

- Quoted in Agger, ibid.

- Michael E. Gardiner, Critiques of Everyday Life (New York: Routledge, 2000), 54.

- Quoted in Gardiner, Ibid., 55.

- Gardiner, Ibid., 58.

- Quoted in Gardiner, Ibid., 62.

- Costas Constandinides, From Film Adaptation to Post-Celluloid Adaptation: Rethinking the Transition of Popular Narratives and Characters across Old and New Media (New York: Continuum, 2010), 3.

- Costas Constandinides, Ibid., 23. Emphasis in original.

- Constandinides, Ibid., 24. Emphasis in original.

- Ruth Prigozy, “The Perils of Adaptation” in “The Case Gets Curious: Debates on Benjamin Button, From Story to Screen,” The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review, Vol. 7 (2009), 3-33, 16.

- Mark Browning, David Fincher: Films That Scar (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2010), 115.

- See further Jonathan Gray, Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts (New York: New York University Press, 2010). Gray argues that paratextual material, such as promotional material or DVD bonus features, perform substantial work in how consumer groups might approach a work or derive certain kinds of meanings from that work.

- See further John T. Caldwell, Production Cultures: Industrial Reflexivity and Critical Practice in Film and Television (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008). Caldwell principally argues that industry practitioners are engaged in many of the same kinds of self-theorizing that media studies scholars regularly engage. As such, his notion of “reflexivity” sees the production of media texts as theoretically informed and discursively imagined for particular ends by an array of media producers.

- “Director’s Commentary with David Fincher,” The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, DVD (2009).

- Richard Maltby, Hollywood Cinema, 2nd ed. (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 371.

- “Director’s Commentary with David Fincher,” ibid.

- “Director’s Commentary with David Fincher,” ibid.

- Barbara Robertson, “What’s Old Is New Again,” Computer Graphics World, Jan. 2009, 8-16, 8.

- Barbara Robertson, Ibid., 10.

- Robertson, Ibid., 12.

- James N. Gilmore, “Will You Like Me When I’m Angry? Discourses of the Digital in Hulk and The Incredible Hulk,” in Superhero Synergies: Comic Book Characters Go Digital, eds. James N. Gilmore and Matthias Stork (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014), 11-26.

- For more information on what Dan North has called the synthespian, or the computer-generated actor, see: Dan Norrth, Performing Illusions: Cinema, Special Effects, and the Virtual Actor (London: Wallflower Press, 2008).

- The Birth of Benjamin Button, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, DVD (2009).

- I borrow the term “intertextual relay” loosely from Gregory Lukow and Steven Ricci, “The ‘Audience’ Goes ‘Public’: Intertextuality, Genre, and the Responsibilities of Film Literacy,” On Film No. 12 (Spring 1984), 29-36.

- “Director’s Commentary with David Fincher,” ibid.

- Ricard Maltby, Ibid., 381.

- Maltby, Ibid., 382.

- See further, Richard Dyer, Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2004).

- See further, Kristin Thompson, “The Concept of Cinematic Excess,” in Film Theory and Criticism, 6th ed., eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 513-524.

- Béla Balázs, “The Face of Man,” in Film Theory and Criticism, 6th ed., eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 316-321, 316.

- Roland Barthes, “Garbo’s Face,” Mythologies (New York: Hill and Wang, 2012), 73-75, 74.

- “Director’s Commentary with David Fincher,” ibid.

- Interviews from The Birth of Benjamin Button, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, DVD (2009).

- Cynthia Fuchs, “What All the Fuss is About: Making Brad Pitt in Thelma & Louise, Thelma & Louise Live! The Cultural Afterlife of an American Film, ed. Bernie Cook (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007), 146-167, 161.

- Cynthia Fuches, Ibid., 163.

- Wesley Morris, Ibid.

- Kathryn Lee Seidel, “’And the Oscar Goes to…’: The Curious Case of Benjamin Button’s Fountain of Youth,” “The Case Gets Curious: Debates on Benjamin Button, From Story to Screen,” The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review, Vol. 7 (2009), 3-33, 27.

- Andre Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” What is Cinema? Vol. 1 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005),9- 16, 14.

- For more information about the production of World War Z, see: Laura M. Holson, “Brad’s War,” Vanity Fair, June 2013 (Link Accessed 8 Feb. 2014.)

The Curious Adaptation of 'Benjamin Button': Or, the Dialogics of Brad Pitt's Face by James N. Gilmore is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License