Urban Script: Constructing the Site Through Narrative and Documentary Structures

By Diane Davis-Sikora

As a spatial art, architecture has a strong affinity with film. Every space has a story to tell. Rooms, buildings, and cities all house memories of their evolution and existence. Some stories are literally written in walls, from hieroglyphics to stained glass, while others are triggered by the experiences and memories of a space’s inhabitants. Through narrative and imagery, film captures the imagination, and as a sequential art reveals the most elusive material of space: time. It is no wonder architects have been, and continue to be, fascinated with film, and are increasingly using movies to portray and analyze their work.

Gradually, more academics are beginning to explore direct applications of digital filmmaking processes in architecture to push the limits of representation beyond traditional, static orthographic projections and routine fly-throughs. This work has contributed greatly to the advancement of design thinking in architecture, and has broken new ground along two primary paths: 1) digital video as source material for motion-based mapping and live action drawings (e.g., the student work of Martha Skinner, Brian McGrath and Jean Gardner), and 2) animated video as final design proposal (e.g., student work of Nic Clear and discussions by Geoff Manaugh). Yet even within this range of growing explorations, documentary form in particular has remained an underutilized resource for spatial and analytical inquiry.

So let me tell you a story....

Since the fall of 2003, I have directed fifth-year and graduate-level architecture studios that focused on the use of digital filmmaking and documentary techniques as the principal method of site analysis, concept development, and design. In studio, students were asked to develop stories that, through their craft and telling, express the culture and memories of a place.

When I began this method six year ago, the benefits were immediately apparent. The process of placing students on site, with cameras in an open and unscripted manner, required them to develop stories based on first-hand observation and information gathered by way of personal interviews, testimonials, and individual accounts. Filmmaking emphasizes the immediacy of the recorded site, which stands in direct contrast to architecture’s more traditional, “distanced view” methods that involve data gathered by site photography, statistics, building code research, and mapping analysis.

In response to those practices, students were asked to produce two types of videos: 1) a site documentary, and 2) a speculative narrative that depicts new site stories. In the first exercise, students developed a five-minute documentary based upon one of five predefined site attributes (lifecycles, histories, cultures, ecologies, and haptics). The production style was to be determined by the students’ overall site observations and tactical level of “objectivity.” A range of documentary models and techniques emerged from this exercise over the years including variations of amateur travelogues, political/propaganda cinema, and city films based on daily lifecycles. Collectively these examples begin to form a framework from which to consider prospective hybridized and cross-disciplinary models of documentary.

Travelogues can serve as an instructive tool in studying a chain of site-specific activities. In this student project (Figure 1), more allegedly “neutral” guided tours served to lead the traveling filmmaker and audience through a set of unexpected places identified by the raconteur. Heather Norris Nicholson observes:

Geography, like travel, often entails searching for difference. Seeking differences can, at times also reveal similarities and continuities. The traveling amateur filmmaker contributes a rich visual dimension to the study of past geographies, although the cinematic representation of continuity and change can be ambiguous in its interweaving of fact and fiction.1

As each account records only one of many possible journeys, this model can serve as a comparative tool though the deployment of multiple points of view. This tactic may also be combined with more hybridized documentary techniques to stress commonalities among journeyers (see discussion of Figure 9).

FIGURE 1 – Excerpts from Video (J. Leiter and M. Serdinak)

Other student film accounts were less “neutral” in their testimony and mood. Figure 2 illustrates a sequence from a video whose theme, “ecology,” is represented through a black and white montage of urban desolation and decay. The “neutrality” of documentary form is initially challenged by the sobering and thematically paradoxical selection of video sequences; such editorialized biases fly in the face of traditional classification of documentary. Bruzzi notes that “the extent to which material has been assimilated, concentrated and selected in traditional expository documentaries makes theorists uneasy, as does the domination of commentary and of a single perspective.”2 A subsequent sequence, however, neutralized the narrative’s initial partiality through a depiction of more ecologically sensitive experiences within the same urban milieu. The intense color and mobile tracking shots stand in stark contrast to the bleak depiction of urban destitution in the opening sequence.

FIGURE 2 – Excerpts from Video (K. Riegsecker, A. Rosekelly, and T Brautigam)

Multiple or simultaneous points of view through split-screens was a device deployed in two student projects (Figures 3 and 4). This method is useful in studying the physical ordering, layering, and systems of disclosure within more complex domains. Arrangements of still, scrolling, and panning shots are composed to defamiliarize a once familiar urban space.3

FIGURE 3 - Excerpts from Video (R. O’Neill, P. Bowman, and B. Linc)

FIGURE 4 - Excerpts from Video (T. Kelly, J. Rach, and M. Kalac)

The movie depicted in Figure 3 incorporated interviews of joyful childhood accounts to counter the somber rhythm and mood of the opening sequence. The act of recording and editing an interview is invaluable from a data collection point of view and has the power to challenge an architect’s biases and preconceptions.

The second video exercise drew from the findings of the original documentaries, and it asked students to produce architectural concepts and strategies for a mixed-use development on the given site. This corresponding project was conducted for the first time in the fall 2007. After four weeks of program development and schematic design, students participated in an intensive two-week filmmaking workshop to develop narrative videos about their design proposals

The workshop was led by two members of the London-based film and media production company Squint/Opera, a studio that produces short films about the built environment. Squint/Opera’s work is well known for its stunning visual and high post-production value that blends humor with brilliant storytelling. Through the workshop students became familiar with all aspects of film production including storyboarding, production planning, shooting, editing, sound collection, digital compositing, and animation. At the conclusion of the workshop, each student presented a narrative movie that forecasted his or her future project.

Two projects used humor as a form of persuasion. The first video, a romantic comedy, portrays scenarios of chance encounter in which two characters meet while engaging in everyday activities as a direct result of the project’s proposed programmatic blending.

Video (J. Finn)4

While this video depicts a fictitious narrative that anticipates a “day in the life” of a future project, it strives for an appearance of “truthfulness” in its portrayal of human interaction on that given day. It is within this context that one might begin to categorize such work as an emergent form of hybridized documentary. Of truth and creativity in documentary films Henrik Juel writes:

But it must be noted that the “truth” of a film can be understood in other ways. A lot of facts or statements about facts that can be verified may be present even in a fiction film. The whole story may be pure fantasy, the characters fictitious and the behavior of the actors may consist of incredible stunts - but still the film may be striving for “truth” in another sense of the word: true emotions and perhaps even to illustrate some more general truths about human life.5

If film theory is beginning to classify documentary on a sliding scale of “authenticity,” then such scenario-based digital animations might find themselves in the range of docufiction or mocumentary. Figure 9, a travelogue of a tourist’s vacation to Cleveland, Ohio, depicts a couple’s experience from the airport to the site, and highlights their need for a series of amenities (medical, cultural, and luxury) that are later encountered within a proposed design project. Part travelogue and part mocumentary, this traveler’s tale offers a window into the world of consumer consumption and leisure activity sponsored by the proposed design project.

FIGURE 9 – Excerpts from Video (J. Leiter and M. Serdinak)

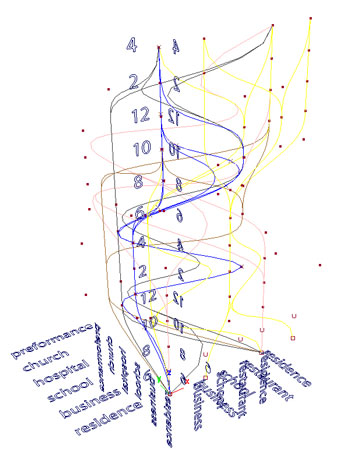

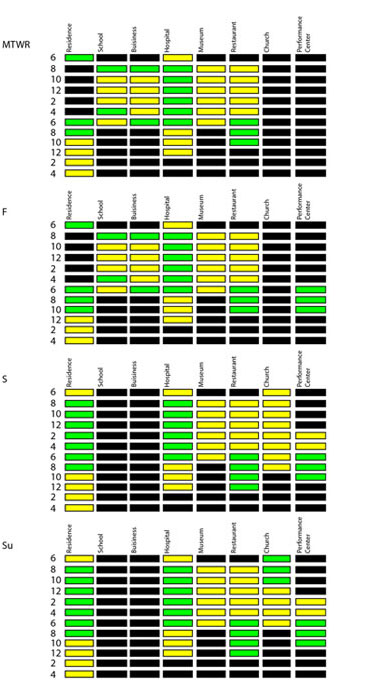

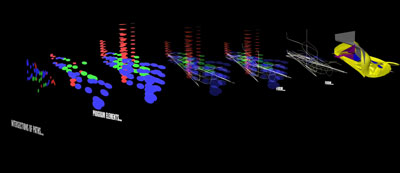

Figures 10 – 16 depict images from a movie about an urban transformation from an underutilized setting to an environment that supports activity 24 hours a day. Based upon the observation that the site is primarily inactive, the student developed a range of building and site activities that complemented events within the site’s adjacent buildings to promote a 24-hour lifecycle. The student surveyed all the surrounding buildings and documented when they were in use and for what given activity. He then mapped that information against the site proper, and formed both building and site programs. His documentary shows time passing along a timeline indicated at the bottom of the frame while highlighting these moments of inactivity within the associated buildings.

Video (B.Miller)6

Figures 10 and 11 are illustrations of the program activities within the surrounding building charted through time. Figure 10 maps this information in three dimensions with X and Y axes depicting the existing program, and Z illustrating time of day.

FIGURE 10 – Program Activity Diagram (B. Miller)

Figure 11 graphs the existing building program with days of week and time of day.

FIGURE 11 – Program Activity Diagram (B. Miller)

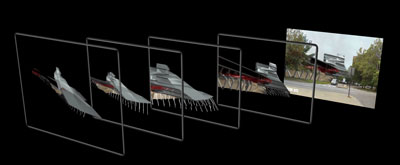

The activity diagram in Figure 10 was then placed on the existing site and scaled to align with a proposed set of circulation pathways and activity nodes. The lines of these pathways were then used as profile lines to generate the building’s form (Figures 12 and 13).

FIGURE 12 – Excerpts from Video (B. Miller)”

FIGURE 13 – Excerpts from Video (B. Miller)

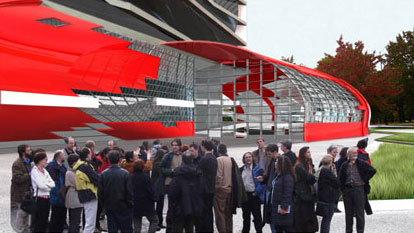

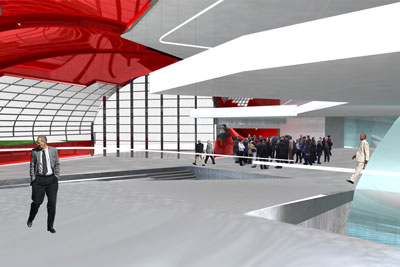

The documentary ends with a depiction of the proposed building in situ (Figures 14-16).

FIGURE 14 – Perspective Rendering (B. Miller)

FIGURE 15 – Perspective Rendering (B. Miller)

FIGURE 16 – Perspective Rendering (B. Miller)

The data-driven maps and animation sequences within this video more clearly align with documentary’s traditional agenda. The video records the conditions of the existing site from which a proposition evolves; past and future coalesce into a single documentary form.

Such hybridization of fact and fiction suggests that architecture and documentary filmmaking may share a middle ground. From the fusion of reality and fiction in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man (1956) and “soft-scripted” programs such as Curb Your Enthusiasm and The Office, to the blending of live action and animation in such films as American Splendor (2003) and Sabiston’s Snack and Drink (2000), hybrid forms of documentary offer architecture exciting new ways to expand their narrative vocabulary. The two disciplines have much to share and learn from one another. An engagement in conversations about these respective arts would undoubtedly yield many compelling discoveries about new ways to write relevant stories that enhance the art and craft of architecture.

NOTES

- Nicholson, Heather Norris. “Telling Travelers’ Tales: The World through Home Movies.” Engaging Film. Eds. Tim Cresswell and Deborah Dixon. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002. 62.

- Bruzzi, Stella. “Narration: the Film and Its Voice.” New Documentary: A Critical Introduction. London: Routledge, 2000. 49.

- Nunn, Heather. Book Review. New Documentary: A Critical Introduction. May 2003. Scope. April 2009. http://www.scope.nottingham.ac.uk/bookreview.php?issue=may2003&id=400§ion=book_rev.

- These videos are the product of a two week filmmaking workshop for a group of Kent State University's architecture graduate students. During the workshop, students produced 90 second videos that describe their design concepts for a mixed-use development in University Circle. The workshop was directed by the award-winning, London based film and media production company Squint/Opera, and was made possible by the generous support of University Circle Incorporated.

- Juel, Henrik. “Defining Documentary Film.” P.O.V. Issue 22. December 2006. April 2009. http://pov.imv.au.dk/Issue_22/section_1/artc1A.html.

- These videos are the product of a two week filmmaking workshop for a group of Kent State University's architecture graduate students. During the workshop, students produced 90 second videos that describe their design concepts for a mixed-use development in University Circle. The workshop was directed by the award-winning, London based film and media production company Squint/Opera, and was made possible by the generous support of University Circle Incorporated.

© Davis-Sikora 2009 All Rights Reserved